Dear Voyagers: How your billion-year journey carries true love

Ann Druyan, creative director on the Voyager golden discs, reflects on the two spacecraft’s epic journeys—and on Carl Sagan, the love of her life.

Dear Voyagers,

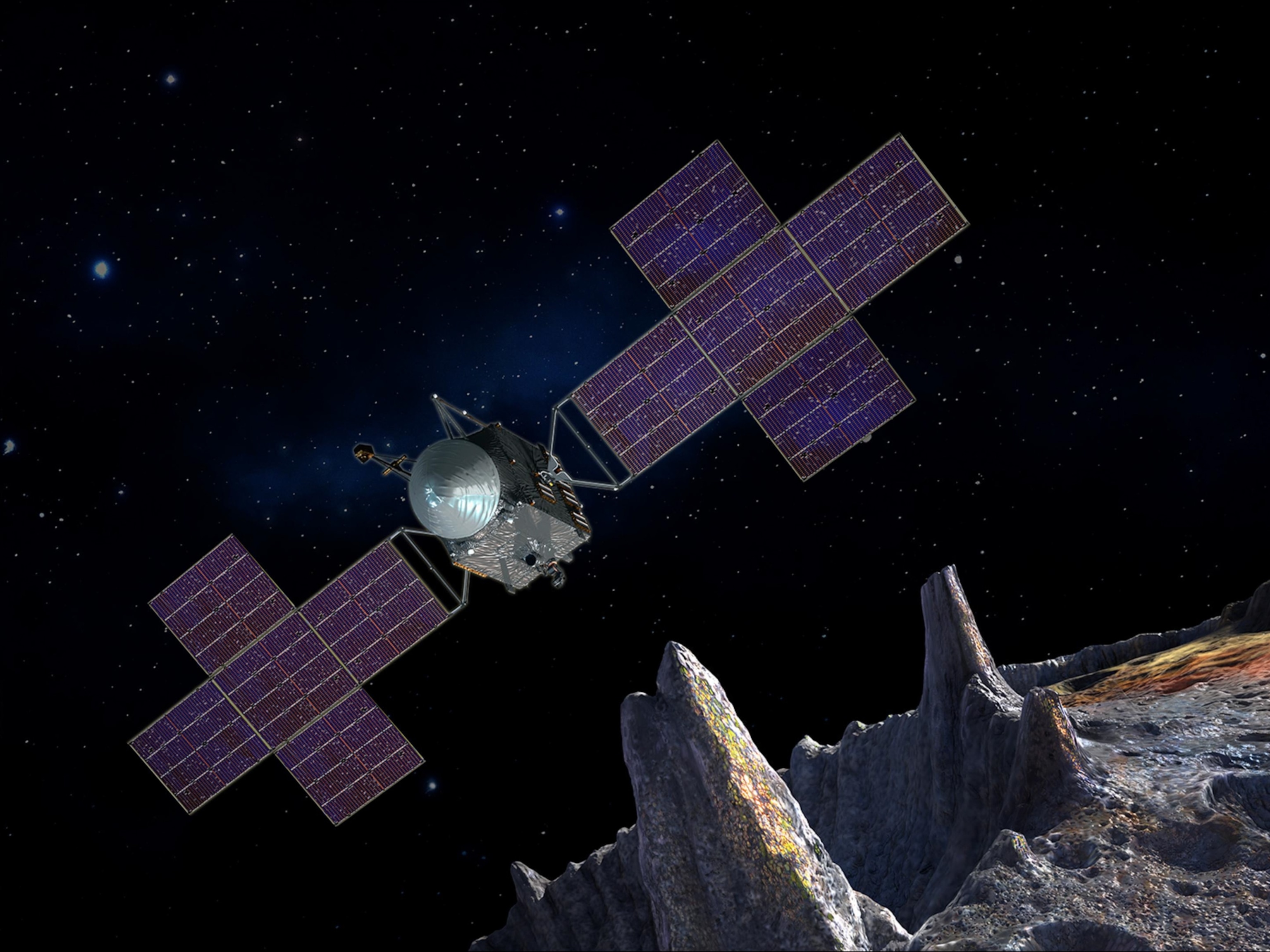

You, the farthest objects we have ever touched, now venture beyond that place where the sun’s wind gives way to roaring interstellar gales; far, far away—and yet I feel close to you. My own life attained lift-off when you did. I was 27 years old when you were in the last stages of your assembly. Carl Sagan and I had known each other as friends and colleagues for a couple of years. We fell in love in 1977 while collaborating on the message that you carry. At the same moment that you left Earth to discover and explore other worlds and to blaze our trail to the stars, we were launched on our own life trajectory. You have been on my mind ever since.

The golden discs affixed to both of you are rich in information, including our return address. The scientific hieroglyphic on them that resembles a burst of fireworks is actually a map of the frequencies of the thirteen nearest pulsars. We think that these rapidly rotating neutron stars—virtually inexhaustible natural beacons, each identifiable by their unique rate of spin—will point the way to our sun and its system of worlds.

Countless times I have tried to imagine that I am flying along with you at 38,000 miles an hour past gas giants and ice worlds, as you leave the shallows of the cosmic ocean, bullet-like, even under the punishing assault of cosmic rays.

I have fantasized your discovery by an extraterrestrial civilization. They reel in one of you derelict spacecraft, assessing your Model-T technology, and pore over the symbols on your golden disc, as Champollion and Young once did in their efforts to decipher the texts of ancient Egypt. But your deeper message is hidden beneath. Someone figures this out and pries off the cover to find 27 pieces of music from the world’s cultures, 118 images of life here, greetings in the languages of humans and others, and an audio essay about life on Earth.

The crackle of thunder awaits them. A mother’s first words to her newborn. A cricket’s song. An hour of meditation by a young woman newly fallen in true love.

I was that woman.

Fast Facts: Voyager 1 and 2

Agency: NASA

Voyager 1 Launch Date: September 5, 1977

Voyager 2 Launch Date: August 20, 1977

Launch Vehicle: Martin Marietta Titan IIIE

Launch Mass: 1,591.5 lbs (721.9 kg)

Power Source: 420-watt radioisotope thermal generator

Voyager 1 Enters Interstellar Space: August 25, 2012

Voyager 2 Enters Interstellar Space: November 5, 2018

Just days after Carl and I realized we would spend the rest of our lives together, I meditated for an hour while blindfolded, hooked up to every human monitoring device then known. The signals from my mind and heart—the most intimate message on the record—were translated into data and paired on the golden records with a strangely similar rasping, that of the most distant sound ever recorded back then: a pulsar.

Now, I am seventy. Yet the feelings of that long-ago spring afternoon remain fresh and astounding. It was the first day of June, and I was searching for the piece of music that would honor China’s 2,500-year-old continuous tradition. I did not know a single thing about Chinese music, so the search for its exemplar had been especially challenging. Once I felt sure I had found it, I left a message for Carl at his hotel in Tucson. We had never kissed or even joked about our feelings for each other, but when he returned my call, in the course of an exchange of about a dozen words, we had decided to marry.

And marry we did—in every way possible. Our families, our work, our hearts and minds and days and nights were blissful in their oneness, for the next two decades, until his death.

I and everyone I know will be dust for more than fifty thousand years before you near another star (unless some spacefarer should flag you down). But even if you are never claimed, you two have already taught us many things. Your dispatches from the outer solar system revealed new moons, geysers, volcanoes, sub-surface oceans, hurricanes of a ferocity that would fracture even our extended scale of categories, and even the very shape of our solar system as it moves through the Milky Way galaxy.

Under Carl’s leadership, you gave us another gift: that lesson in humility known as the “pale blue dot,” a portrait of our one-pixel world taken from out by Neptune. It is a way to grasp our true circumstances that can pierce even the fiercest form of denial. To see it is to know that we all live on a tiny dot. I wonder how long the petty chieftains and polluters can hold onto their delusions now that we’ve seen the picture you took and sent home to us, Voyager 1? From where you are now, Earth would be invisible.

For me you are more than machine. You are also an apt metaphor for Carl. In him, as in you, our science and humanity were united without conflict. Wonder and skepticism, imagination and rigor, ambition and inclusion, passion and reason, audacity and humility, precision and tenderness—none ever at the cost of the other—all combined to make him, what he was, and you, what you are.

Our collective human memory can barely reach back ten thousand years. Generations of scientists have been reconstructing the past of our species, our planet, and our universe. Thanks to them, we have an idea of what happened nearly 14 billion years ago. Your projected shelf life measures on that same enormous time scale. You are expected to complete four to twenty trips around the galaxy with our music, our images, our messages, intact. Since you have exceeded your mission specifications in every other way, I favor the optimistic view of a five-billion-year long shelf-life for your message. That’s likely longer than the future history of life on Earth. Your voices may still speak for us when our sun has become a red giant and all terrestrial remnants of our existence have been reduced to ash.

Even then, because of you, we can imagine that five thousand million years from now, our blues and our ragas, and a heart at its greatest fullness, will sing on.

Ad astra, my darlings.

My love and I are with you always,

Ann

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads