There are currently around 75,000 children in care in England. These children will grow up seriously disadvantaged by their childhood experiences – despite government interventions.

Care leavers, for example, are six times more likely to enter the criminal justice system, are more likely to be homeless – and often have low levels of emotional well-being.

Children who have grown up in care are also more likely to struggle to pass exams, get a job, or to attend further and higher education – almost 40% of care leavers aged 19 to 21 are not in education, employment or training.

Many people who grow up in care have gaps in their childhood memories, not least unanswered questions such as “Why was I taken into care?” or “Where did I live?” And for many care leavers, accessing their care records can be part of a therapeutic process of coming to terms with the past.

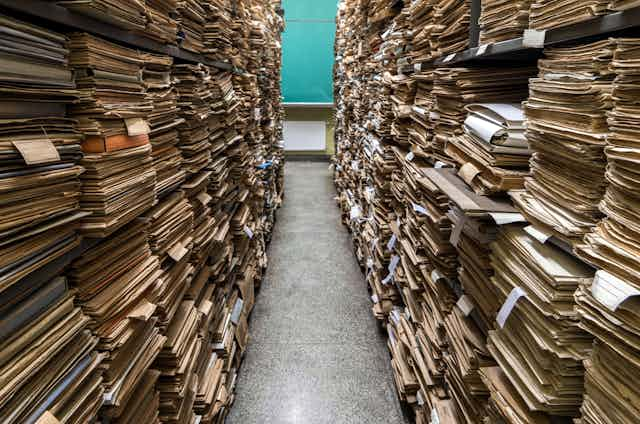

But many care leavers who try to access records held by local authorities and charities often find their files are missing. And when people do receive their records, they have often been heavily redacted, or censored to remove any “third party information” – such as names of parents, siblings, family members and carers.

The power of the past

As part of our recent research, we worked with people who grew up in care to find out what it was like for them to access their care records. The MIRRA project, led by UCL with the Care Leaver’s Association and the charity Family Action, collected interview and focus group data from more than 80 care leavers, social workers and information managers working for local authorities and charities who look after children.

We found that accessing care records can play a significant role for care leavers – acting as a “paper self” long after they have left care. Care leaver Gina explained:

There came a point where I wanted to know where I’d been, I wanted to know who’d fostered me, because there was little chunks of my life missing, like where I’d gone to school? Did I have any friends? How long was I there?

Susan, who was in care in the 1970s and 1980s, told us why her records matter:

For the first time in my life, I was free. And it was all because of those records. It was very emotional. It was so important to me … it can put things away so that you can carry on with the rest of your life.

But our research also shows how the voices of children and young people who lived in care were often entirely missing from records. And this can cause significant distress and upset – as John-george explained:

One of the most profound things for me about the file is my lack of voice. It is totally stolen and words are put in your mouth, saying this is how you feel about certain occasions and certain people, and at times there’s conflict with what I believe.

The voices, experiences and feelings of children and young people in care are rarely heard in their records. And they have few family or childhood photographs or stories that might answer their questions. All of which can have a huge impact on their sense of self later in life and the memories they have about their childhood.

Even if they are able to access their records, many care leavers are handed files rendered virtually meaningless by the thick black lines of redaction. Nor is there support or signposting to organisations that can help.

Care leaver Jackie explained how this can be deeply troubling, making people feel powerless, rejected and dehumanised:

There’s pieces of paper that are just blacked out, and there’s absolutely nothing on them. And then there’s other pieces of paper where there’s just a sentence in there. And I’m looking at it … and all it’s showing me is I’ve been rejected again.

A child’s voice

Care leavers have often had very difficult experiences as children, and making the transition into independent adult life can be tough. But our research highlights the vital role care records can play in helping care leavers to get a better understanding of their past.

Records can help care leavers to understand why they went into care. They may help them come to terms with what happened and to understand why they could not be looked after at home. But it can be traumatic to read care files. So instead of a culture of record-keeping for compliance, there needs to be a culture of caring record-keeping. Encouraging children in care to write about what they know about their life story can help to add their voice in the records. As can allowing them to keep personal memory objects, such as toys or photographs.

As our research highlights, care records must put the experiences of the child at the heart of the file – from what is written down in the first place, to how records are kept and stored, to how decisions are made about access. All of which can make a big difference to someone at what can be a very vulnerable time in their life.