-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Natasha Wiggins, Joanne Droney, Kabir Mohammed, Julia Riley, Katherine E Sleeman, Understanding the factors associated with patients with dementia achieving their preferred place of death: a retrospective cohort study, Age and Ageing, Volume 48, Issue 3, May 2019, Pages 433–439, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz015

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

dying in one’s preferred place is a quality marker for end-of-life care. Little is known about preferred place of death, or the factors associated with achieving this, for people with dementia.

to understand preferences for place of death among people with dementia; to identify factors associated with achieving these preferences.

adults with a diagnosis of dementia who died between December 2015 and March 2017 and who were registered on Coordinate My Care, an Electronic Palliative Care Coordination System.

retrospective cohort study.

multivariable logistic regression investigated factors associated with achieving preferred place of death.

we identified 1,047 people who died with dementia; information on preferred and actual place of death was available for 803. Preferred place of death was most commonly care home (58.8%, n = 472) or home (39.0%, n = 313). Overall 83.7% (n = 672) died in their preferred place. Dying in the preferred place was more likely for those most functionally impaired (OR 1.82 95% CI 1.06–3.13), and with a ceiling of treatment of ‘symptomatic relief only’ (OR 2.65, 95% CI 1.37–5.14). It was less likely for people with a primary diagnosis of cancer (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.28–0.97), those who were ‘for’ cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.16–0.62) and those whose record was created longer before death (51–250 days (ref <50 days) OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.38–0.94).

most people with dementia want to die in a care home or at home. Achieving this is more likely where goals of treatment are symptomatic relief only, indicating the importance of advance care planning.

Key points

This is the first study to compare preferred and actual place of death for people dying with dementia.

Preferred place of death was most commonly care home (58.8%, n = 472) or home (39.0%, n = 313).

There are modifiable factors that impact the likelihood of a patient dying in their preferred place.

People with a ceiling of treatment of symptomatic treatment only were more likely to achieve their preferred place of death.

In this study, low functional status was associated with increased chance of dying in a preferred place.

Introduction

Over the last decade, having choice and control over the place of death has been increasingly considered a marker of a ‘good’ death [1–3]. Given a hypothetical choice, most people would like to die at home [4]. A range of personal, illness-related and environmental factors have been shown to be associated with achieving preferred place of death, including a solid tumour cancer diagnosis, being married, early referral to palliative care, higher performance status, higher socio-economic status and decreasing age [5–7].

Enabling people with dementia to remain in their usual place of residence is considered an essential component of good care [8, 9]. Several studies have looked at where people with dementia die [10–12]. A study from the USA found most people (66.9%) with dementia died in a nursing home, in contrast to their age-related peers with cancer who either died at home (37.8%) or in an acute hospital (35.4%) [12]. In England, place of death in dementia has shifted from hospitals to care homes in recent years [11]. Analysis of deaths from dementia across five countries demonstrated that place of death was related to age, sex, available hospital and nursing home beds, and country of residence [10].

Understanding preferences for place of death, and the factors that influence achieving these, could guide service development and lead to more people dying in their preferred place. Despite its prominence in national and international strategies, [13, 14] there is a paucity of research addressing preferred place of death in people with dementia [15]. The aim of this study was to understand preferences for place of death among people with dementia, and to identify the factors associated with achieving these preferences.

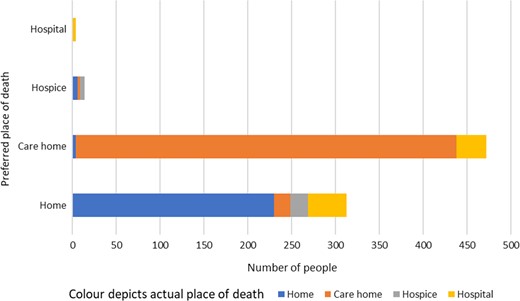

Actual place of death in the context of the decedents’ preferred place of death.

Methods

Design: retrospective cohort study

Setting and data source

The study used anonymised data collected as part of Coordinate My Care (CMC). CMC is an Electronic Palliative Care Co-ordination System (EPaCCS), hosted by the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, and available to all patients with chronic illness living in London. CMC records are created by trained healthcare professionals with input from patients and their carers, and aim to facilitate communication and coordination of healthcare. CMC enables patients to record their preferences for end of life care such as preferred place of death, ceiling of treatment and resuscitation status, as well as clinical details and social support information. CMC records are stored on a secure digital platform that enables access by healthcare providers including acute hospitals, primary care, ambulance services, and emergency departments. To date, CMC records have been created for over 50,000 patients.

Population

Adults with a diagnosis of dementia who died between 1 December 2015 and 31 March 2017, and who had a CMC record were included. Data were extracted in September 2017.

Variables

Individual-level variables included gender and age (extracted in bands of <79, 80–84, 85–89, 90–94 and 95+).

Illness-related variables included primary diagnosis (coded as dementia, cancer or other) and type of dementia (Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body, Vascular, unspecified). Information on functional status, derived from WHO performance status score, was dichotomised into ‘0, 1, 2, 3’ (from fully active to capable of only limited self-care) and ‘4’ (totally confined to bed or chair) based on the data distribution.

Variables related to record creation included the type of consent obtained for completion of the record (coded as individual consent obtained, lasting power of attorney or a ‘best interests’ decision). The time between record creation and an individual’s death was measured in days and categorised as <50 / 51–250 / 251–450 / >450 days.

Variables related to end of life decision making included preferred place of death (categorised as care home/hospital/home/hospice/unknown), cardiopulmonary resuscitation status (for/not for cardiopulmonary resuscitation; people without a decision were included with the ‘for resuscitation’ group based on standard UK clinical practice). Capacity to make a decision about cardiopulmonary resuscitation was categorised as yes/no/clinician unsure. The ceiling of treatment was recorded in CMC as ‘full active treatment including cardiopulmonary resuscitation/full active treatment including in acute hospital setting but not cardiopulmonary resuscitation/treatment of any reversible conditions (including acute hospital setting if needed) but not for any ventilation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation/treatment of any reversible conditions but only in the home or hospice setting: keep comfortable/symptomatic treatment only: keep comfortable/Not completed’.

Actual place of death was categorised as care home/hospital/home/hospice/unknown.

Analysis

Data were cleaned and checked. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the total study population, those who achieved their preferred place of death, those who did not, and patients for whom either preferred or actual place of death was missing. Correlation between explanatory variables was assessed using Pearson correlation, and variables with a correlation of 0.7 or higher were removed from analysis.

The primary outcome was achieving preferred place of death (yes/no), derived from creation of a new variable where preferred place of death (care home/hospital/home/hospice) matched actual place of death (care home/hospital/home/hospice).

Unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression was used to understand factors associated with achieving preferred place of death. Explanatory variables were selected according to a priori hypotheses (age and gender) and significance in unadjusted analyses (P < 0.1) and forced to stay in the model. The area under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess how best the model predicts the outcome. Data analysis was done in IBM SPSS statistics v24.

The Reporting of Studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-Collected Health Data (RECORD) extension to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines was used in the reporting of this study [16, 17].

Approvals

Patients consent to the use of their anonymised information for research at the time of consenting to creation of a CMC record. This project was approved by the Royal Marsden Committee for Clinical Research.

Results

In total, 1,047 people with a diagnosis of dementia and who died between December 2015 and March 2017, were identified.

Most people were women (64.6%) and the commonest age group at death was 85–89 (26.8%). The primary diagnosis was dementia for 794 (75.8%) and cancer in 105 cases (10.0%). Cardiac disease (41, 4.4%), vascular disease (20, 2.2%), respiratory disease (16, 1.7%), and neurological disease (15, 1.6%) made up the remaining 148 cases (14.1%). Most people (882, 84.2%) had a WHO performance status of 4 (Table 1).

Characteristics of all individuals in the study, including those who died in their preferred place and those who did not

| Characteristic . | All (%) n = 1047 . | Died in their preferred place n = 672 (%) . | Did not die in their preferred place n = 131 (%) . | No PPD recorded n = 181 . | No APD recorded n = 63 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 377 (36.0) | 223 (33.2) | 51 (38.9) | 76 (42.0) | 27 (42.9) |

| Female | 670 (64.6) | 449 (66.8) | 80 (61.1) | 105 (58.0) | 36 (57.1) |

| Age at death | |||||

| Not completed | 37 (3.5) | 20 (3.0) | 7 (5.3) | 8 (4.4) | 2 (3.2) |

| <79 | 144 (13.8) | 88 (13.1) | 20 (15.3) | 28 (15.5) | 8 (12.7) |

| 80–84 | 173 (16.5) | 114 (17.0) | 19 (29.0) | 30 (16.6) | 10 (15.9) |

| 85–89 | 281 (26.8) | 173 (25.7) | 38 (29.0) | 53 (29.3) | 17 (27.0) |

| 90–94 | 256 (24.5) | 161 (24.0) | 31 (23.7) | 42 (23.2) | 22 (34.9) |

| 95+ | 156 (14.9) | 116 (17.3) | 16 (12.2) | 20 (11.0) | 4 (6.3) |

| Primary diagnosis | |||||

| Dementia | 794 (75.8) | 520 (77.4) | 88 (67.2) | 141 (77.9) | 45 (71.4) |

| Cancer | 105 (10.0) | 56 (8.3) | 22 (16.8) | 20 (11.0) | 7 (11.1) |

| Other | 148 (14.1) | 96 (14.3) | 21 (16.0) | 20 (11.0) | 11 (17.5) |

| Type of dementia | |||||

| Alzheimers | 253 (24.2) | 170 (25.3) | 38 (29.0) | 31 (17.1) | 14 (22.2) |

| Vascular | 229 (21.9) | 150 (22.3) | 25 (19.1) | 43 (23.8) | 11 (17.5) |

| Lewy-body | 29 (2.8) | 20 (3.0) | 4 (3.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (4.8) |

| Unspecified | 536 (51.6) | 332 (49.4) | 64 (48.9) | 105 (58.0) | 35 (55.0) |

| WHO performance status | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| 2 | 22 (2.1) | 8 (1.2) | 4 (3.1) | 9 (5.0) | 1 (1.6) |

| 3 | 140 (13.4) | 68 (10.1) | 31 (23.7) | 31 (17.1) | 10 (15.9) |

| 4 | 882 (84.2) | 596 (88.7) | 94 (71.8) | 140 (77.3) | 52 (82.5) |

| Consent type for CMC record | |||||

| Patient consent | 129 (12.3) | 68 (10.1) | 29 (22.1) | 25 (13.8) | 7 (11.1) |

| ‘Best interests’ decision | 813 (77.7) | 532 (79.2) | 90 (68.7) | 144 (79.6) | 47 (74.6) |

| Lasting Power of Attorney | 105 (10.0) | 72 (10.7) | 12 (9.2) | 12 (6.6) | 9 (14.3) |

| Number of days between record creation and death | |||||

| <50 | 538 (51.4) | 381 (56.7) | 54 (41.2) | 89 (49.2) | 31 (48.7) |

| 51–250 | 339 (32.4) | 200 (29.8) | 58 (44.3) | 68 (37.5) | 24 (37.6) |

| 251–450 | 82 (7.8) | 51 (7.6) | 16 (12.2) | 18 (9.9) | 4 (6.3) |

| >450 | 8 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (1.6) |

| Done in retrospect | 43 (4.1) | 38 (5.7) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (4.8) |

| Mean = 80.53 | |||||

| Preferred place of death | |||||

| Care home | 521 (49.8) | 434 (64.6) | 38 (29.0) | 49 (77.8) | |

| Home | 326 (31.1) | 230 (34.2) | 83 (63.4) | 13 (20.6) | |

| Hospice | 15 (1.4) | 5 (0.7) | 9 (6.9) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Hospital | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Unknown | 181 (17.3) | 181 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| CPR decision | |||||

| Not for CPR | 946 (90.4) | 634 (94.4) | 111 (84.7) | 149 (82.3) | 52 (82.6) |

| For CPR | 101 (9.6) | 38 (5.6) | 21 (15.3) | 32 (17.7) | 11 (17.4) |

| Patient capacity re CPR | |||||

| Had capacity | 70 (6.7) | 39 (5.8) | 17 (13.0) | 11 (6.3) | 3 (4.8) |

| No capacity | 802 (76.6) | 538 (80.1) | 89 (67.9) | 129 (71.3) | 46 (73.0) |

| Clinician unsure | 74 (7.1) | 57 (8.5) | 5 (3.8) | 9 (5.0) | 3 (4.8) |

| Not completed | 101 (9.6) | 38 (5.7) | 20 (15.3) | 32 (17.7) | 11 (17.5) |

| Ceiling of treatment | |||||

| Full active treatment | 34 (3.3) | 10 (1.4) | 8 (6.1) | 13 (7.2) | 3 (4.8) |

| Admission to hospital but no CPR | 110 (10.5) | 59 (8.8) | 21 (16.0) | 34 (18.8) | 5 (8.0) |

| Reversible conditions but stay in community | 343 (32.8) | 218 (32.4) | 47 (35.9) | 56 (30.9) | 22 (34.9) |

| Symptomatic only | 338 (32.3) | 252 (37.5) | 25 (19.1) | 41 (22.7) | 20 (31.7) |

| Not completed | 199 (21.1) | 133 (19.8) | 30 (22.9) | 37 (20.4) | 13 (20.6) |

| Actual place of death | |||||

| Care home | 533 (50.9) | 434 (64.6) | 23 (17.6) | 76 (42.0) | |

| Home | 277 (26.5) | 230 (34.2) | 10 (7.6) | 37 (20.4) | |

| Hospital | 127 (12.1) | 3 (0.4) | 78 (59.5) | 50 (27.6) | |

| Hospice | 33 (3.2) | 5 (0.7) | 20 (15.3) | 8 (4.4) | |

| Not completed | 73 (7.0) | 10 (5.5) | 63 (100.0) |

| Characteristic . | All (%) n = 1047 . | Died in their preferred place n = 672 (%) . | Did not die in their preferred place n = 131 (%) . | No PPD recorded n = 181 . | No APD recorded n = 63 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 377 (36.0) | 223 (33.2) | 51 (38.9) | 76 (42.0) | 27 (42.9) |

| Female | 670 (64.6) | 449 (66.8) | 80 (61.1) | 105 (58.0) | 36 (57.1) |

| Age at death | |||||

| Not completed | 37 (3.5) | 20 (3.0) | 7 (5.3) | 8 (4.4) | 2 (3.2) |

| <79 | 144 (13.8) | 88 (13.1) | 20 (15.3) | 28 (15.5) | 8 (12.7) |

| 80–84 | 173 (16.5) | 114 (17.0) | 19 (29.0) | 30 (16.6) | 10 (15.9) |

| 85–89 | 281 (26.8) | 173 (25.7) | 38 (29.0) | 53 (29.3) | 17 (27.0) |

| 90–94 | 256 (24.5) | 161 (24.0) | 31 (23.7) | 42 (23.2) | 22 (34.9) |

| 95+ | 156 (14.9) | 116 (17.3) | 16 (12.2) | 20 (11.0) | 4 (6.3) |

| Primary diagnosis | |||||

| Dementia | 794 (75.8) | 520 (77.4) | 88 (67.2) | 141 (77.9) | 45 (71.4) |

| Cancer | 105 (10.0) | 56 (8.3) | 22 (16.8) | 20 (11.0) | 7 (11.1) |

| Other | 148 (14.1) | 96 (14.3) | 21 (16.0) | 20 (11.0) | 11 (17.5) |

| Type of dementia | |||||

| Alzheimers | 253 (24.2) | 170 (25.3) | 38 (29.0) | 31 (17.1) | 14 (22.2) |

| Vascular | 229 (21.9) | 150 (22.3) | 25 (19.1) | 43 (23.8) | 11 (17.5) |

| Lewy-body | 29 (2.8) | 20 (3.0) | 4 (3.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (4.8) |

| Unspecified | 536 (51.6) | 332 (49.4) | 64 (48.9) | 105 (58.0) | 35 (55.0) |

| WHO performance status | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| 2 | 22 (2.1) | 8 (1.2) | 4 (3.1) | 9 (5.0) | 1 (1.6) |

| 3 | 140 (13.4) | 68 (10.1) | 31 (23.7) | 31 (17.1) | 10 (15.9) |

| 4 | 882 (84.2) | 596 (88.7) | 94 (71.8) | 140 (77.3) | 52 (82.5) |

| Consent type for CMC record | |||||

| Patient consent | 129 (12.3) | 68 (10.1) | 29 (22.1) | 25 (13.8) | 7 (11.1) |

| ‘Best interests’ decision | 813 (77.7) | 532 (79.2) | 90 (68.7) | 144 (79.6) | 47 (74.6) |

| Lasting Power of Attorney | 105 (10.0) | 72 (10.7) | 12 (9.2) | 12 (6.6) | 9 (14.3) |

| Number of days between record creation and death | |||||

| <50 | 538 (51.4) | 381 (56.7) | 54 (41.2) | 89 (49.2) | 31 (48.7) |

| 51–250 | 339 (32.4) | 200 (29.8) | 58 (44.3) | 68 (37.5) | 24 (37.6) |

| 251–450 | 82 (7.8) | 51 (7.6) | 16 (12.2) | 18 (9.9) | 4 (6.3) |

| >450 | 8 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (1.6) |

| Done in retrospect | 43 (4.1) | 38 (5.7) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (4.8) |

| Mean = 80.53 | |||||

| Preferred place of death | |||||

| Care home | 521 (49.8) | 434 (64.6) | 38 (29.0) | 49 (77.8) | |

| Home | 326 (31.1) | 230 (34.2) | 83 (63.4) | 13 (20.6) | |

| Hospice | 15 (1.4) | 5 (0.7) | 9 (6.9) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Hospital | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Unknown | 181 (17.3) | 181 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| CPR decision | |||||

| Not for CPR | 946 (90.4) | 634 (94.4) | 111 (84.7) | 149 (82.3) | 52 (82.6) |

| For CPR | 101 (9.6) | 38 (5.6) | 21 (15.3) | 32 (17.7) | 11 (17.4) |

| Patient capacity re CPR | |||||

| Had capacity | 70 (6.7) | 39 (5.8) | 17 (13.0) | 11 (6.3) | 3 (4.8) |

| No capacity | 802 (76.6) | 538 (80.1) | 89 (67.9) | 129 (71.3) | 46 (73.0) |

| Clinician unsure | 74 (7.1) | 57 (8.5) | 5 (3.8) | 9 (5.0) | 3 (4.8) |

| Not completed | 101 (9.6) | 38 (5.7) | 20 (15.3) | 32 (17.7) | 11 (17.5) |

| Ceiling of treatment | |||||

| Full active treatment | 34 (3.3) | 10 (1.4) | 8 (6.1) | 13 (7.2) | 3 (4.8) |

| Admission to hospital but no CPR | 110 (10.5) | 59 (8.8) | 21 (16.0) | 34 (18.8) | 5 (8.0) |

| Reversible conditions but stay in community | 343 (32.8) | 218 (32.4) | 47 (35.9) | 56 (30.9) | 22 (34.9) |

| Symptomatic only | 338 (32.3) | 252 (37.5) | 25 (19.1) | 41 (22.7) | 20 (31.7) |

| Not completed | 199 (21.1) | 133 (19.8) | 30 (22.9) | 37 (20.4) | 13 (20.6) |

| Actual place of death | |||||

| Care home | 533 (50.9) | 434 (64.6) | 23 (17.6) | 76 (42.0) | |

| Home | 277 (26.5) | 230 (34.2) | 10 (7.6) | 37 (20.4) | |

| Hospital | 127 (12.1) | 3 (0.4) | 78 (59.5) | 50 (27.6) | |

| Hospice | 33 (3.2) | 5 (0.7) | 20 (15.3) | 8 (4.4) | |

| Not completed | 73 (7.0) | 10 (5.5) | 63 (100.0) |

Characteristics of all individuals in the study, including those who died in their preferred place and those who did not

| Characteristic . | All (%) n = 1047 . | Died in their preferred place n = 672 (%) . | Did not die in their preferred place n = 131 (%) . | No PPD recorded n = 181 . | No APD recorded n = 63 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 377 (36.0) | 223 (33.2) | 51 (38.9) | 76 (42.0) | 27 (42.9) |

| Female | 670 (64.6) | 449 (66.8) | 80 (61.1) | 105 (58.0) | 36 (57.1) |

| Age at death | |||||

| Not completed | 37 (3.5) | 20 (3.0) | 7 (5.3) | 8 (4.4) | 2 (3.2) |

| <79 | 144 (13.8) | 88 (13.1) | 20 (15.3) | 28 (15.5) | 8 (12.7) |

| 80–84 | 173 (16.5) | 114 (17.0) | 19 (29.0) | 30 (16.6) | 10 (15.9) |

| 85–89 | 281 (26.8) | 173 (25.7) | 38 (29.0) | 53 (29.3) | 17 (27.0) |

| 90–94 | 256 (24.5) | 161 (24.0) | 31 (23.7) | 42 (23.2) | 22 (34.9) |

| 95+ | 156 (14.9) | 116 (17.3) | 16 (12.2) | 20 (11.0) | 4 (6.3) |

| Primary diagnosis | |||||

| Dementia | 794 (75.8) | 520 (77.4) | 88 (67.2) | 141 (77.9) | 45 (71.4) |

| Cancer | 105 (10.0) | 56 (8.3) | 22 (16.8) | 20 (11.0) | 7 (11.1) |

| Other | 148 (14.1) | 96 (14.3) | 21 (16.0) | 20 (11.0) | 11 (17.5) |

| Type of dementia | |||||

| Alzheimers | 253 (24.2) | 170 (25.3) | 38 (29.0) | 31 (17.1) | 14 (22.2) |

| Vascular | 229 (21.9) | 150 (22.3) | 25 (19.1) | 43 (23.8) | 11 (17.5) |

| Lewy-body | 29 (2.8) | 20 (3.0) | 4 (3.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (4.8) |

| Unspecified | 536 (51.6) | 332 (49.4) | 64 (48.9) | 105 (58.0) | 35 (55.0) |

| WHO performance status | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| 2 | 22 (2.1) | 8 (1.2) | 4 (3.1) | 9 (5.0) | 1 (1.6) |

| 3 | 140 (13.4) | 68 (10.1) | 31 (23.7) | 31 (17.1) | 10 (15.9) |

| 4 | 882 (84.2) | 596 (88.7) | 94 (71.8) | 140 (77.3) | 52 (82.5) |

| Consent type for CMC record | |||||

| Patient consent | 129 (12.3) | 68 (10.1) | 29 (22.1) | 25 (13.8) | 7 (11.1) |

| ‘Best interests’ decision | 813 (77.7) | 532 (79.2) | 90 (68.7) | 144 (79.6) | 47 (74.6) |

| Lasting Power of Attorney | 105 (10.0) | 72 (10.7) | 12 (9.2) | 12 (6.6) | 9 (14.3) |

| Number of days between record creation and death | |||||

| <50 | 538 (51.4) | 381 (56.7) | 54 (41.2) | 89 (49.2) | 31 (48.7) |

| 51–250 | 339 (32.4) | 200 (29.8) | 58 (44.3) | 68 (37.5) | 24 (37.6) |

| 251–450 | 82 (7.8) | 51 (7.6) | 16 (12.2) | 18 (9.9) | 4 (6.3) |

| >450 | 8 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (1.6) |

| Done in retrospect | 43 (4.1) | 38 (5.7) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (4.8) |

| Mean = 80.53 | |||||

| Preferred place of death | |||||

| Care home | 521 (49.8) | 434 (64.6) | 38 (29.0) | 49 (77.8) | |

| Home | 326 (31.1) | 230 (34.2) | 83 (63.4) | 13 (20.6) | |

| Hospice | 15 (1.4) | 5 (0.7) | 9 (6.9) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Hospital | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Unknown | 181 (17.3) | 181 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| CPR decision | |||||

| Not for CPR | 946 (90.4) | 634 (94.4) | 111 (84.7) | 149 (82.3) | 52 (82.6) |

| For CPR | 101 (9.6) | 38 (5.6) | 21 (15.3) | 32 (17.7) | 11 (17.4) |

| Patient capacity re CPR | |||||

| Had capacity | 70 (6.7) | 39 (5.8) | 17 (13.0) | 11 (6.3) | 3 (4.8) |

| No capacity | 802 (76.6) | 538 (80.1) | 89 (67.9) | 129 (71.3) | 46 (73.0) |

| Clinician unsure | 74 (7.1) | 57 (8.5) | 5 (3.8) | 9 (5.0) | 3 (4.8) |

| Not completed | 101 (9.6) | 38 (5.7) | 20 (15.3) | 32 (17.7) | 11 (17.5) |

| Ceiling of treatment | |||||

| Full active treatment | 34 (3.3) | 10 (1.4) | 8 (6.1) | 13 (7.2) | 3 (4.8) |

| Admission to hospital but no CPR | 110 (10.5) | 59 (8.8) | 21 (16.0) | 34 (18.8) | 5 (8.0) |

| Reversible conditions but stay in community | 343 (32.8) | 218 (32.4) | 47 (35.9) | 56 (30.9) | 22 (34.9) |

| Symptomatic only | 338 (32.3) | 252 (37.5) | 25 (19.1) | 41 (22.7) | 20 (31.7) |

| Not completed | 199 (21.1) | 133 (19.8) | 30 (22.9) | 37 (20.4) | 13 (20.6) |

| Actual place of death | |||||

| Care home | 533 (50.9) | 434 (64.6) | 23 (17.6) | 76 (42.0) | |

| Home | 277 (26.5) | 230 (34.2) | 10 (7.6) | 37 (20.4) | |

| Hospital | 127 (12.1) | 3 (0.4) | 78 (59.5) | 50 (27.6) | |

| Hospice | 33 (3.2) | 5 (0.7) | 20 (15.3) | 8 (4.4) | |

| Not completed | 73 (7.0) | 10 (5.5) | 63 (100.0) |

| Characteristic . | All (%) n = 1047 . | Died in their preferred place n = 672 (%) . | Did not die in their preferred place n = 131 (%) . | No PPD recorded n = 181 . | No APD recorded n = 63 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 377 (36.0) | 223 (33.2) | 51 (38.9) | 76 (42.0) | 27 (42.9) |

| Female | 670 (64.6) | 449 (66.8) | 80 (61.1) | 105 (58.0) | 36 (57.1) |

| Age at death | |||||

| Not completed | 37 (3.5) | 20 (3.0) | 7 (5.3) | 8 (4.4) | 2 (3.2) |

| <79 | 144 (13.8) | 88 (13.1) | 20 (15.3) | 28 (15.5) | 8 (12.7) |

| 80–84 | 173 (16.5) | 114 (17.0) | 19 (29.0) | 30 (16.6) | 10 (15.9) |

| 85–89 | 281 (26.8) | 173 (25.7) | 38 (29.0) | 53 (29.3) | 17 (27.0) |

| 90–94 | 256 (24.5) | 161 (24.0) | 31 (23.7) | 42 (23.2) | 22 (34.9) |

| 95+ | 156 (14.9) | 116 (17.3) | 16 (12.2) | 20 (11.0) | 4 (6.3) |

| Primary diagnosis | |||||

| Dementia | 794 (75.8) | 520 (77.4) | 88 (67.2) | 141 (77.9) | 45 (71.4) |

| Cancer | 105 (10.0) | 56 (8.3) | 22 (16.8) | 20 (11.0) | 7 (11.1) |

| Other | 148 (14.1) | 96 (14.3) | 21 (16.0) | 20 (11.0) | 11 (17.5) |

| Type of dementia | |||||

| Alzheimers | 253 (24.2) | 170 (25.3) | 38 (29.0) | 31 (17.1) | 14 (22.2) |

| Vascular | 229 (21.9) | 150 (22.3) | 25 (19.1) | 43 (23.8) | 11 (17.5) |

| Lewy-body | 29 (2.8) | 20 (3.0) | 4 (3.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (4.8) |

| Unspecified | 536 (51.6) | 332 (49.4) | 64 (48.9) | 105 (58.0) | 35 (55.0) |

| WHO performance status | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| 2 | 22 (2.1) | 8 (1.2) | 4 (3.1) | 9 (5.0) | 1 (1.6) |

| 3 | 140 (13.4) | 68 (10.1) | 31 (23.7) | 31 (17.1) | 10 (15.9) |

| 4 | 882 (84.2) | 596 (88.7) | 94 (71.8) | 140 (77.3) | 52 (82.5) |

| Consent type for CMC record | |||||

| Patient consent | 129 (12.3) | 68 (10.1) | 29 (22.1) | 25 (13.8) | 7 (11.1) |

| ‘Best interests’ decision | 813 (77.7) | 532 (79.2) | 90 (68.7) | 144 (79.6) | 47 (74.6) |

| Lasting Power of Attorney | 105 (10.0) | 72 (10.7) | 12 (9.2) | 12 (6.6) | 9 (14.3) |

| Number of days between record creation and death | |||||

| <50 | 538 (51.4) | 381 (56.7) | 54 (41.2) | 89 (49.2) | 31 (48.7) |

| 51–250 | 339 (32.4) | 200 (29.8) | 58 (44.3) | 68 (37.5) | 24 (37.6) |

| 251–450 | 82 (7.8) | 51 (7.6) | 16 (12.2) | 18 (9.9) | 4 (6.3) |

| >450 | 8 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (1.6) |

| Done in retrospect | 43 (4.1) | 38 (5.7) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (4.8) |

| Mean = 80.53 | |||||

| Preferred place of death | |||||

| Care home | 521 (49.8) | 434 (64.6) | 38 (29.0) | 49 (77.8) | |

| Home | 326 (31.1) | 230 (34.2) | 83 (63.4) | 13 (20.6) | |

| Hospice | 15 (1.4) | 5 (0.7) | 9 (6.9) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Hospital | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Unknown | 181 (17.3) | 181 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| CPR decision | |||||

| Not for CPR | 946 (90.4) | 634 (94.4) | 111 (84.7) | 149 (82.3) | 52 (82.6) |

| For CPR | 101 (9.6) | 38 (5.6) | 21 (15.3) | 32 (17.7) | 11 (17.4) |

| Patient capacity re CPR | |||||

| Had capacity | 70 (6.7) | 39 (5.8) | 17 (13.0) | 11 (6.3) | 3 (4.8) |

| No capacity | 802 (76.6) | 538 (80.1) | 89 (67.9) | 129 (71.3) | 46 (73.0) |

| Clinician unsure | 74 (7.1) | 57 (8.5) | 5 (3.8) | 9 (5.0) | 3 (4.8) |

| Not completed | 101 (9.6) | 38 (5.7) | 20 (15.3) | 32 (17.7) | 11 (17.5) |

| Ceiling of treatment | |||||

| Full active treatment | 34 (3.3) | 10 (1.4) | 8 (6.1) | 13 (7.2) | 3 (4.8) |

| Admission to hospital but no CPR | 110 (10.5) | 59 (8.8) | 21 (16.0) | 34 (18.8) | 5 (8.0) |

| Reversible conditions but stay in community | 343 (32.8) | 218 (32.4) | 47 (35.9) | 56 (30.9) | 22 (34.9) |

| Symptomatic only | 338 (32.3) | 252 (37.5) | 25 (19.1) | 41 (22.7) | 20 (31.7) |

| Not completed | 199 (21.1) | 133 (19.8) | 30 (22.9) | 37 (20.4) | 13 (20.6) |

| Actual place of death | |||||

| Care home | 533 (50.9) | 434 (64.6) | 23 (17.6) | 76 (42.0) | |

| Home | 277 (26.5) | 230 (34.2) | 10 (7.6) | 37 (20.4) | |

| Hospital | 127 (12.1) | 3 (0.4) | 78 (59.5) | 50 (27.6) | |

| Hospice | 33 (3.2) | 5 (0.7) | 20 (15.3) | 8 (4.4) | |

| Not completed | 73 (7.0) | 10 (5.5) | 63 (100.0) |

Most (946, 90.4%) were not for cardio-pulmonary resuscitation and 802 (76.6%) people did not have capacity to make and communicate decisions around cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The ceiling of treatment was not completed for 199 (21.1%) people. The ceiling of treatment was full active treatment for 34 people (3.3%); admission to hospital but not for cardiopulmonary resuscitation for 110 people (10.5%); treatment of reversible conditions but not for hospital admission for 343 people (32.8%); and symptomatic relief only for 338 people (32.3%).

Consent for creation of a CMC record was a ‘best interests’ decision for 813 people (77.7%). The patient gave consent in 129 (12.3%) of cases and the person’s lasting power of attorney for health and welfare gave consent in 105 cases (10.0%).

The records of 538 (51.4%) people were created <50 days before death; 8 (0.8%) records were created >450 days before death. The mean number of days between record creation and death was 80.5 and the interquartiles were: 25:6; 50:32; 75:125.

Preferred place of death was care home for 521 (49.8%), home for 326 (31.1%), hospice for 15 (1.4%) and hospital for 4 (0.4%). Preferred place of death was unknown for 181 people (17.3%). Actual place of death was documented for 974 (93.0%) people. Of those, 533 (50.9%) died in a care home, 277 (26.5%) died at home, 127 (12.1%) died in hospital and 33 (3.2%) died in a hospice. There were 803 people for whom preferred and actual place of death were known. Figure 1 preferred place of death was achieved by 672 (83.7%) of the people for whom both the preferred and actual place of death were known and not achieved by 131 (16.3%) (Table 1).

In unadjusted analysis, a primary diagnosis of dementia, not being for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, absence of capacity regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision, ceiling of treatment of ‘symptomatic only’ and ‘treat reversible conditions but stay in the community’, WHO performance status of 4, a ‘best interests’ or lasting power of attorney consent for the creation of the CMC record and a smaller number of days before death the record was created were associated with achieving preferred place of death.

In the multivariable model, the following factors remained significantly associated with higher odds of dying in the preferred place: a ceiling of treatment for ‘symptomatic relief only’ compared to ‘full active treatment’, performance status 4 compared to 0, 1, 2 or 3, cardiopulmonary resuscitation status and having a CMC record created closer to death. A primary diagnosis of cancer was associated with decreased odds of achieving preferred place of death (Table 2). The ROC area under the graph was 0.72 (0.67–0.77) P = 0.03.

Multivariable logistic regression investigating factors associated with dying in the preferred place

| Characteristic . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | Ref | 0.674 |

| Female | 1.10 (0.70–1.73) | |

| Age at death | ||

| <79 | Ref | 0.754 (overall) |

| 80–84 | 1.16 (0.56–2.42) | 0.695 |

| 85–89 | 0.90 (0.47–1.74) | 0.761 |

| 90–94 | 0.92 (0.46–1.82) | 0.804 |

| 95+ | 1.36 (0.60–3.03) | 0.446 |

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| Dementia | Ref | 0.111 (overall) |

| Cancer | 0.52 (0.28–0.97) | 0.039 |

| Other | 0.80 (0.45–1.41) | 0.435 |

| CPR decision | ||

| Not for CPR | Ref | 0.001 |

| For CPR | 0.32 (0.16–0.62) | |

| Ceiling of treatment | ||

| Active treatment including hospital admission ± CPR | Ref | 0.029 (overall) |

| Reversible conditions but stay in community | 1.59 (0.86–2.91) | 0.136 |

| Symptomatic only | 2.65 (1.37–5.14) | 0.004 |

| Not completed | 2.00 (1.02–3.93) | 0.044 |

| WHO performance status | ||

| 0, 1, 2 or 3 | Ref | 0.030 |

| 4 | 1.82 (1.06–3.13) | |

| Consent for CMC record | ||

| Usual consent | Ref | 0.232 (overall) |

| Best interests | 1.62 (0.91–2.88) | 0.098 |

| Lasting power of attorney | 1.76 (0.74–4.24) | 0.204 |

| Number of days before death the record was created | ||

| <50 | Ref | 0.030 |

| 51–250 | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | 0.026 |

| 251–450 | 0.50 (0.25–0.99) | 0.048 |

| >451 | 0.16 (0.02–1.24) | 0.079 |

| Characteristic . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | Ref | 0.674 |

| Female | 1.10 (0.70–1.73) | |

| Age at death | ||

| <79 | Ref | 0.754 (overall) |

| 80–84 | 1.16 (0.56–2.42) | 0.695 |

| 85–89 | 0.90 (0.47–1.74) | 0.761 |

| 90–94 | 0.92 (0.46–1.82) | 0.804 |

| 95+ | 1.36 (0.60–3.03) | 0.446 |

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| Dementia | Ref | 0.111 (overall) |

| Cancer | 0.52 (0.28–0.97) | 0.039 |

| Other | 0.80 (0.45–1.41) | 0.435 |

| CPR decision | ||

| Not for CPR | Ref | 0.001 |

| For CPR | 0.32 (0.16–0.62) | |

| Ceiling of treatment | ||

| Active treatment including hospital admission ± CPR | Ref | 0.029 (overall) |

| Reversible conditions but stay in community | 1.59 (0.86–2.91) | 0.136 |

| Symptomatic only | 2.65 (1.37–5.14) | 0.004 |

| Not completed | 2.00 (1.02–3.93) | 0.044 |

| WHO performance status | ||

| 0, 1, 2 or 3 | Ref | 0.030 |

| 4 | 1.82 (1.06–3.13) | |

| Consent for CMC record | ||

| Usual consent | Ref | 0.232 (overall) |

| Best interests | 1.62 (0.91–2.88) | 0.098 |

| Lasting power of attorney | 1.76 (0.74–4.24) | 0.204 |

| Number of days before death the record was created | ||

| <50 | Ref | 0.030 |

| 51–250 | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | 0.026 |

| 251–450 | 0.50 (0.25–0.99) | 0.048 |

| >451 | 0.16 (0.02–1.24) | 0.079 |

Multivariable logistic regression investigating factors associated with dying in the preferred place

| Characteristic . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | Ref | 0.674 |

| Female | 1.10 (0.70–1.73) | |

| Age at death | ||

| <79 | Ref | 0.754 (overall) |

| 80–84 | 1.16 (0.56–2.42) | 0.695 |

| 85–89 | 0.90 (0.47–1.74) | 0.761 |

| 90–94 | 0.92 (0.46–1.82) | 0.804 |

| 95+ | 1.36 (0.60–3.03) | 0.446 |

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| Dementia | Ref | 0.111 (overall) |

| Cancer | 0.52 (0.28–0.97) | 0.039 |

| Other | 0.80 (0.45–1.41) | 0.435 |

| CPR decision | ||

| Not for CPR | Ref | 0.001 |

| For CPR | 0.32 (0.16–0.62) | |

| Ceiling of treatment | ||

| Active treatment including hospital admission ± CPR | Ref | 0.029 (overall) |

| Reversible conditions but stay in community | 1.59 (0.86–2.91) | 0.136 |

| Symptomatic only | 2.65 (1.37–5.14) | 0.004 |

| Not completed | 2.00 (1.02–3.93) | 0.044 |

| WHO performance status | ||

| 0, 1, 2 or 3 | Ref | 0.030 |

| 4 | 1.82 (1.06–3.13) | |

| Consent for CMC record | ||

| Usual consent | Ref | 0.232 (overall) |

| Best interests | 1.62 (0.91–2.88) | 0.098 |

| Lasting power of attorney | 1.76 (0.74–4.24) | 0.204 |

| Number of days before death the record was created | ||

| <50 | Ref | 0.030 |

| 51–250 | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | 0.026 |

| 251–450 | 0.50 (0.25–0.99) | 0.048 |

| >451 | 0.16 (0.02–1.24) | 0.079 |

| Characteristic . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | Ref | 0.674 |

| Female | 1.10 (0.70–1.73) | |

| Age at death | ||

| <79 | Ref | 0.754 (overall) |

| 80–84 | 1.16 (0.56–2.42) | 0.695 |

| 85–89 | 0.90 (0.47–1.74) | 0.761 |

| 90–94 | 0.92 (0.46–1.82) | 0.804 |

| 95+ | 1.36 (0.60–3.03) | 0.446 |

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| Dementia | Ref | 0.111 (overall) |

| Cancer | 0.52 (0.28–0.97) | 0.039 |

| Other | 0.80 (0.45–1.41) | 0.435 |

| CPR decision | ||

| Not for CPR | Ref | 0.001 |

| For CPR | 0.32 (0.16–0.62) | |

| Ceiling of treatment | ||

| Active treatment including hospital admission ± CPR | Ref | 0.029 (overall) |

| Reversible conditions but stay in community | 1.59 (0.86–2.91) | 0.136 |

| Symptomatic only | 2.65 (1.37–5.14) | 0.004 |

| Not completed | 2.00 (1.02–3.93) | 0.044 |

| WHO performance status | ||

| 0, 1, 2 or 3 | Ref | 0.030 |

| 4 | 1.82 (1.06–3.13) | |

| Consent for CMC record | ||

| Usual consent | Ref | 0.232 (overall) |

| Best interests | 1.62 (0.91–2.88) | 0.098 |

| Lasting power of attorney | 1.76 (0.74–4.24) | 0.204 |

| Number of days before death the record was created | ||

| <50 | Ref | 0.030 |

| 51–250 | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | 0.026 |

| 251–450 | 0.50 (0.25–0.99) | 0.048 |

| >451 | 0.16 (0.02–1.24) | 0.079 |

Discussion

This study provides the first data on preferences for place of death among people with dementia, and the factors associated with achieving these, in a large English sample. Most people with dementia had a recorded preference to die in a care home or at home, and 83.7% died in their preferred location. Dying in the preferred place was more likely for individuals with a ceiling of treatment of ‘symptomatic relief only’, for people with the poorest performance status, and for those patients who had a shorter time interval between CMC record creation and death. Having a primary diagnosis of cancer (with a concurrent diagnosis of dementia) and being ‘for’ cardio-pulmonary resuscitation were associated with being less likely to die in the preferred place.

Half of our cohort had a recorded preference to die in a care home and a third at home. This is similar to a small cross-sectional survey of patients with dementia in Japan [18] which found that 46% (15/29) had a preferred place of death of home and 42% (14/29) had a preferred place of death of care home. We found just 1.4% of our cohort had a recorded preference to die in a hospice (n = 15). In contrast, research by Gomes et al. found 41% of people aged over 75 if faced with a hypothetical diagnosis of advanced cancer had a preference for hospice death [4], which may reflect setting (Gomes’ study excluded people living in care homes) or diagnosis.

In this study, a high proportion of people (83.7%) died in their preferred place. A 1 year mortality follow back study in the Netherlands found 44.4% (malignant diagnoses) and 19.4% (non-malignant diagnoses) of people achieved their preferred place of death [19]. The high proportion of people dying in their preferred place in our study is likely to reflect the setting: registration on an Electronic Palliative Care Coordination System is more likely among those most engaged with end of life decision making [20, 21]. Other studies using Electronic Palliative Care Coordination Systems have found that 55.0–77.5% of people achieved their preferred place of death [22, 23].

Just under 80% of the patients in our cohort had a ceiling of treatment recorded, indicating that making decisions on, and recording information about, ceilings of treatment is feasible in this patient population. While multiple ceiling of treatment options are available in CMC, for the majority of our cohort with dementia, the ceiling of treatment was focussed in the community. Having an increasingly ‘palliative’ ceiling of treatment was associated with greater odds of dying in the preferred place, illustrating the importance of making ceiling of treatment decisions with this patient population. We found people with the least good performance status were more likely to die in their preferred place. This contrasts with a UK study in people with lung cancer in which poor performance status increased the chances of dying in hospital [6].

The association between poor performance status and achieving preferred place of death may reflect unmeasured confounders; residential or nursing care have been shown to be less likely to transition into hospital near the end of life [24, 25]. We were unable to include information on place of residence in our model. Having a primary diagnosis of cancer was associated with lower likelihood of dying in the preferred place. This contrasts with a meta-analysis concluding that a non-cancer diagnosis increases chances of ‘incongruence’ between preferred and actual place of death [26], though our data should be interpreted with caution due to small numbers of people with cancer. We found people whose CMC record was created closer to death had higher odds of dying in their preferred place, which may reflect changing preferences as death approaches [27, 28]. It may be that the high proportion of records created fewer than 4 months prior to death reflect that CMC is predominantly used for terminal care planning rather than ‘supportive and palliative’ care. It was not possible to determine whether the preferred place of death decision recorded was made by the person with dementia or in their ‘best interests’. The influences on preferences for care for older people are complex [29].

This is the first study to investigate achievement of preferred place of death at an individual level for people with dementia. Our cohort was relatively large. However, it was limited to people with a CMC record and the generalisability of our findings to other populations, for example rural populations or those without access to electronic palliative care records should be investigated. Our study was limited by the variables available. We were not able to investigate several factors likely to influence whether preferred place of death is achieved, such as place of residence (care home or home), marital status, or presence of caregivers.

This study has provided important data on factors that may be important in dying in the preferred place for people with dementia. Further studies are needed to explore other aspects of end of life care quality, for example transitions into hospital in the last months of life. In addition, the role and effectiveness of Electronic Palliative Care Coordination Systems in improving the end of life care experiences requires further evaluation. The ability to link these data to primary and secondary care data would be valuable.

Conclusion

Despite a national and international focus on achieving preferred place of death as a marker of the quality of end of life care, to date there has been a paucity of knowledge about the wishes of people dying with and from dementia. We found that care homes are the most common preferred place of death for people with dementia. Given the increase in the projected number of people dying from dementia in 2040 [30] investment in care homes is urgently needed. In addition, the study has highlighted the importance of discussing and agreeing ceilings of treatment to achieve end of life preferences, and the importance of revisiting these preferences as death approaches.

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank Dr Benjamin Allin for assistance with data analysis.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest: JR is clinical lead for Coordinate My Care.

Declaration of Sources of Funding: KES is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinician Scientist Fellowship (CS-2015-15-005). This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. NW received funding from the Kirby Laing Foundation, via Cicely Saunders International, to fund the MSc for which this research was completed.

Comments