Not so long ago, we might have looked forward to a heatwave, particularly here in the UK – a chance to enjoy the sunshine and balmy evenings. Heatwaves, however, can cause a range of health problems. If you cannot find somewhere cool or off-load the excess heat from your body it can be very serious indeed and the extreme heat seen in recent years, such as the July 2022 heatwave, has resulted in a significant number of excess deaths.

Keeping cool is particularly problematic when the heat is ‘humid’. This is when the air contains lots of water vapour. High humidity makes it very hard for sweat to evaporate from our bodies which means that we cannot cool down. For people working outside or in overheating buildings, especially where the work is physically demanding, humid heat is a big problem. The world is getting warmer, and many places are also seeing increases in water vapour and the resulting humidity.

Researching exposure to high humidity and dry heat events

The distinction between humid heat and dry heat is a relatively new area of research. What we do know is that dry heat events can be much ‘hotter’ than humid heat events, and at present appear to be more lethal, or at least high temperature shows a stronger relationship with mortality than high humidity. However, humidity plays an important role in health and ‘productivity’. People ‘feel’ worse when the humidity is high and cannot maintain physical activity at the same level. This could mean slower progress in construction, lower yields for manual food harvesting or fewer completed tasks within a factory, which have economic as well as health impacts.

Climate change and heat health is the focus of some of the research being undertaken by the Weather and Climate Science for Services Partnership (WCSSP) programme, supported by the UK Government’s Newton Fund. A CSSP China project has been developing a global dataset of extreme wet bulb temperature (Tw) and air temperature (T) – HadISDH.extremes – that enables us to study the current level of exposure of regions to both high humidity heat events and dry heat events and measure the rate at which such events have increased in severity and frequency over the last 50 years. Wet bulb temperature is a common way of measuring humidity, is less complex than other measures of heat, and provides a critical threshold of 35°C beyond which the human body cannot survive for long. This is because human skin temperature is around 35°C. If the wet bulb temperature and skin temperature are both 35°C, sweating no longer works because the air next to the skin cannot hold any additional water and the body cannot cool down. In reality, even physically fit people struggle to undertake normal light activity when the wet bulb temperature gets within a few degrees of this threshold.

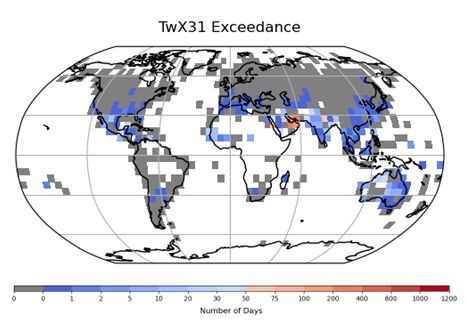

The HadISDH.extremes dataset allows us to identify those regions already experiencing very high wet bulb temperatures. Figure 1 shows that 31°C has already been reached several times over much of the tropics. This new dataset also allows us to investigate the two different types of events explicitly and explore what might be termed ‘stealth heat events’ where the air temperature might not be excessively high, but the wet bulb temperature is high enough to affect health and productivity.

Further global research

Other WCSSP programme research is also focused on heat health including:

- Researching which weather patterns bring humid heat over China, a region where high humidity heat is commonplace already because the hottest season also tends to be the wettest. Climate change will make this worse;

- Producing a global gridded dataset of ‘sector specific’ indices related to temperature such as ‘Heating Degree Days’, a ‘Warm Spell Duration Index’ and ‘Excess Heat Factor’;

- Using satellite Land Surface Temperature to produce an interactive high resolution gridded dataset of temperature indices and urban hot spots;

- Quantifying the current and future population exposed to high heat over Brazil, for present day and for a range of potential futures depending on future greenhouse gas emissions. This data has also been used globally;

- Exploring the predictability of heatwaves and their corresponding impact on population relating to weather patterns over South Africa;

- Investigating levels of solar and infrared radiation on people from surrounding building layout and fabric, which can significantly affect the heat impact in warm weather; and

- Assessing the contribution of human-induced climate change to heatwaves and specific heat events, including how much more likely they become.

As our climate continues to change, research into health impacts will be critical to enable appropriate adaptation measures to be put in place. And by reducing emissions, we can minimise the worst impacts of climate change.

You must be logged in to post a comment.