| Key Strategies for a Focus on Creative Writing in ELT – Using Mentor Texts in Teacher Education

Janice Bland |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Student language teachers exploring literary texts for language education mostly focus on what is written, and the opportunities that could arise for stimulating classroom discussions. In teacher education, helping student teachers discover how a powerfully persuasive text is created is frequently overlooked. With this article I explore whether a brief unit with specific guidelines for creative writing in teacher education could achieve several related aims: supporting student teachers’ confidence in guiding children to see how compelling texts achieve impact, supporting student teachers’ confidence in how the activity of creative writing might work in the classroom, and supporting them in setting creative writing tasks themselves. I show how mentor texts, or literary models – in this article by authors David Almond and Philip Pullman – can illustrate sensory imagery, lexical chains, and the enlivening effect of semantic and phonological repetition. Such devices foreground language, catching the reader’s attention, while ideally enriching and extending the sense of the text – the meanings and perceptions. Examples from creative writing units I have taught over numerous years illustrate how student teachers can acquire a grasp of the mechanics of creative writing, hopefully to later help their own students enjoy both reading and writing. I contend that student teachers can best recognize the power of intentional repetition and inventive language choices through their own efforts in creative writing.

Keywords: David Almond, Philip Pullman, creative writing, mentor text, poetic devices, teacher education

Dr Janice Bland is Professor of English Education, Nord University, Norway, and Visiting Professor at Oslo Metropolitan University. Her research interests are picturebooks, young adult fiction, creative writing, visual and critical literacy, English language and literature pedagogy, global issues, ecocriticism, interculturality and drama. Her latest book is Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy (2022).

Introduction

In this article on creative writing, I draw on my experience teaching creative writing in language teacher education in Germany and Norway over nearly two decades, and on my student teachers’ experiences with creative writing in their classrooms. My deliberations consist in whether brief but focused creative writing input in teacher education (circa eight hours face-to-face specialist training for undergraduate student teachers with tasks to complete at home) could (1) increase confidence among student teachers in their own writing competence, and (2) increase confidence among student teachers to set meaningful creative writing tasks for school students. I find it important to ascertain the efficacy of short-term teaching, as teacher education programmes are often crowded, and achieving more than one desirable aim in the limited time available seems very advantageous. Norwegian teachers must study for five years to gain a master, and primary and lower secondary school teachers tend to be generalists – in the sense that they must cover several school subjects – so the hours they can commit to any one subject in their studies are considerably limited.

Poetic writers for children and young adults have been an important influence on my design for a creative writing unit, which always includes a focus on one mentor text that all student teachers read, and which could also be read in primary or lower secondary school. A consummate literary model or mentor text (Gallagher, 2014; Moses, 2014) can scaffold the novice creative writer, whether in school or in teacher education, in that a degree of freedom is reduced, so reducing the scope for failure, while the poetic devices are highlighted. In this way, the scaffolding effect of mentor texts can heighten the chances of success while sensitising learners to language possibilities, choices, and constraints. As Carol Read (2015) writes, ‘creativity doesn’t happen in a vacuum. There is always something that stimulates and underpins the generation of children’s original thinking, such as an idea, picture, text, story, object, question or problem, or some combination of these’ (p. 29). Debra Myhill (2020) emphasizes developing children’s rhetorical repertoires to help them discover how language will express their nuanced meanings, since ‘linguistic development might be more effectively enabled if we connect linguistic choice and rhetorical purpose’ (p. 199). Therefore, Myhill et al. (2018) point to the use of a literary model to deepen students’ acquisition of ‘metalinguistic awareness of the repertoire of possibilities of language choices’ (p. 7). Responding to literary texts with creative writing, integrating inventive recreation and the urge to explore linguistic choices, language learners may not only become more confident writers, but more confident readers as well. Alan Maley (2013) highlights the synergy between reading and writing for language learners:

Creative writing also feeds into more creative reading. It is as if, by getting inside the process of creating the text, learners come to intuitively understand how such texts work, and this makes them easier to read. Likewise, the development of aesthetic reading skills provides the learner with a better understanding of textual construction, and this feeds into their writing. (p. 164)

Naomi Baron (2015) similarly emphasizes how reading and writing are intertwined, and that ephemeral online reading habits lead to less precision and stamina in writing: ‘Computers, and now portable digital devices, coax us to skim rather than read in depth, search rather than traverse continuous prose. As a result, how – and how much – we write is already shifting’ (p. xiii). Peter Lutzker (2015, unpaginated) claims there are multiple arguments for an emphasis on literature and creative writing in second language education, asserting that ‘developing the skills called for in both reading literature and creative writing invariably hinges on having enough opportunities to practise both creative writing and the reading of literature.’ Through his recent research in Sweden, Paul Morris (2023) identifies ‘the relief that outlandish creativity and playful writing’ can provide students of English, and adds, ‘if imaginative and creative writing is beneficial to pupils’ well-being, as English teachers we are duty-bound to include it in our practice’ (p. 233). For the adolescents in his study, Morris further expounds how ‘English extends their reach into the world, but also, they can think and write without the emotional baggage of their mother tongue’, while also gaining access to ‘a larger playground for imaginative and speculative thought’ (p. 234).

Authorial Agency and Redressing an Imbalance of Power

Creative writing can offer students more choices in their linguistic behaviour and more initiative in how they deal with a topic. In this sense, creative writing supports a more agentic, more personal and less judgemental approach to writing. Cummins et al. (2015) have researched creative writing and how identity-affirming, dual-language literacy practices usually increase students’ literacy engagement, especially when they have different home languages. They argue that, with the aid of motivating feedback, ‘creative writing and other forms of cultural production or performance (for example, art, drama, video creation, etc.) represent expressions of identity, projection of identity into new social spheres, and re-creation of identity’ (p. 557, emphasis in original). Creative writing sometimes allows the contravention of rules, and in this sense moves away from prescriptive grammar, aligning more with poetic and every-day oral creativity. David Crystal (1998) argues that the playful or ludic function is central to language and ‘should be at the heart of any thinking we do about linguistic issues’ (p. 1), and Guy Cook (2000) has identified copious language play, which often transgresses rules, in everyday discourse.

In a similar vein, but as a children’s literature scholar, Peter Hunt (2010) explores what he calls a childist approach to children’s literature, proposing that poetry for the young may offer ‘an openness of mind to language and its possibilities’ (p. 22) through its celebration of language play. Influential children’s literature scholars write on the importance of valuing young people’s viewpoints and trying to avoid an imbalance of power in our approach to texts for young people. Maria Nikolajeva (2010; 2014) has coined the term aetonormativity, which refers to the view that adult experiences are standard (adult normativity), as often represented in literary texts, while the experiences of children and adolescents are accordingly nonstandard or Other. Nikolajeva compares aetonormativity to heteronormativity and Western ethnocentrism. However, children’s literature can have transgressive potential, which can be discovered and explored, as suggested by literature scholars such as Bradford et al. (2007), Deszcz-Tryhubczak (2016), Oziewicz (2015) and Reynolds (2007), while educationalists such as Bland (2022), Leland et al. (2013) and Simpson and Cremin (2022) emphasize reading literature as social practice, working dialogically with students in the classroom, while also exploring the critical literacy opportunities of literary texts for children. Particularly in the language classroom, where motivation and self-efficacy are all important for confidence in the new role of speaking and writing in another language, this exploration of, and sensitivity to, power dynamics could support students’ counter-hegemonic voices. Students’ voices can be expressed both through their oral contributions and their writing, and creative writing might be experienced as emancipation from the domination of curriculum constraints, or the distorting impact of assessment practices.

The Mechanics of Creative Writing

Introducing insights and strategies from mentor texts can guide and support children, adolescents, and student teachers as they develop their own creative writing in a process-oriented way (rather than product-oriented). There are certain techniques that can help students articulate their thoughts persuasively and find formulations to express ideas and feelings with nuance. Noticing poetic techniques in mentor texts and trying them out is important for creativity, which involves playing with ideas freely, according to Read (2015), while ‘at the same time, it involves disciplined thinking, curiosity, and attention to detail and effort. It also needs to be underpinned by the development of specific strategies and skills’ (p. 29). The understanding of poetic devices should include how language and meaning can be shaped by consciously and carefully connecting choices of words, formulaic sequences, and poetic images with a rhetorical objective. This accords with Crystal’s statement (2004) that ‘the educational aim today is to place grammar within a frame of reference which demonstrates its relevance to the active and creative tasks of language production and comprehension’ (p. 10). Besides, the capacity to write persuasively is of societal importance and central to educational success in school (Cremin & Oliver, 2017) and is also an aspect of academic writing in tertiary education.

As a mnemonic, I introduce five key areas or strategies to notice and practise when focusing on creative writing (though these areas constantly overlap in practice).

- Stylistic cohesion – attention to lexical chains, intentional lexical repetition, explicit connectivity such as anaphora and the melodic tricolon, or rhetorical rule of three.

- Setting and sensory imagery – attention to delivering sensory impressions, so the reader can see, hear, and bodily feel the scene, potentially smell and taste certain details. Dramatic sounds and onomatopoeia energize the writing and help the reader hear as well as visualize the scene.

- Phonological patterns – attention to patterned sound such as rhythm, alliteration, and potentially rhyme, which create the perception of hearing a text even when it is read silently.

- Characterization – attention to details that bring a character alive, and attention to coherence that creates a convincing character.

- Variation – attention to the opportunities of schema refreshment, deviation from the familiar, dissolving of boundaries, typographic experimentation and potentially breaking rules.

In the following, I will look at each of these key areas in turn, providing examples from five mentor texts: Wild Girl, Wild Boy (Almond, 2002), The Savage (Almond, illus. McKean, 2008), Mouse Bird Snake Wolf (Almond, illus. McKean, 2013), The Firework-Maker’s Daughter (Pullman, 1995) and Clockwork (Pullman, 1996). Excerpts from student teachers’ work (2020-22), which are extracted from activities that are integral to a compact creative writing unit, provide further illustration. The tuition takes place as two four-hour sessions, which form part of a larger teacher education module for second-year undergraduates in Norway.

Stylistic cohesion

Synonyms, collocations, and ellipses help to provide cohesion, so that a text glues well together. While synonyms create redundancy, they also create shades of meaning and lexical density. Repetition is the basis of all language and literature, just as it is the basis of music and all arts that rely on pattern. Repetition is also essential for first and second language acquisition, and re-formulations in literature are far more than mere duplications of language: they can be a means of foregrounding language, of poetic play, of catching the reader’s attention and therefore making language noticeable for language learners. Repeated language patterns can intensify meaning when fresh iterations provide added layers of significance: ‘the accretion or attenuation of meaning from one iteration of the word to the next’ as Corinna Russell (2018, p. 49) writes in discussing the trope of repetition in William Blake’s poetry.

A lexical chain, which refers to a string of words in proximity that add semantic depth by an accumulation of related meaning, is a powerful way to create cohesion. The following extract illustrates a lexical chain around ‘story’: wizards, fairies, once upon a time, adventures and they all lived happily ever after; it is taken from David Almond’s micro-graphic novel, The Savage (2008), about a boy called Blue and his invention of a savage, whom he creates to deal with his grief:

Once I started writing the story, it was like I couldn’t stop, which was strange for me. I’d never been one for stories. I couldn’t stand all the stuff about wizards and fairies and ‘once upon a time’ and ‘they all lived happily ever after’. That’s not what life’s like. Me, I wanted blood and guts and adventures, so that’s what I wrote. (p. 12)

The poetic device known as the rhetorical rule of three, or tricolon, is playful and extremely effective in delivering tension, rhythm and a pleasing pattern to a text. The power of the three-fold pattern may in part emanate from the magical triples of fairy tales and oral storytelling, and the third of the triple often suggests a climax. The tricolon is an inviting and catchy pattern that is ubiquitous in children’s literature, poetry, and oral literature as well as in advertising, political slogans, and speeches. Encouraging students to use the tricolon means inspiring them to enrich their vocabulary and create an energetic textual rhythm; as an example – a tricolon can create meaning that evolves, mutates, and transmutes to fresh significance.

Creative writing is not a silent mode, and language learners (and student teachers) can better attend to the rhythm of their writing if they read their own texts aloud. This also allows them to focus on the poetic and other auditory aspects of the text, just like listeners of oral storytelling. Even in predominantly literate societies, aspects of pre-literate orality still strongly influence poetry, speech writing and other creative uses of contemporary written language and can often be identified in children’s literature as a cohesive rhetorical force. Orality researcher Walter Ong (2002) refers to serious thought being intertwined with methods of remembering, such as, ‘heavily rhythmic, balanced patterns, in repetitions or antitheses, in alliterations and assonances’ (p. 34). Repetition and near repetition are important for the storyteller as a mnemonic tool and crucial to enable the listener to follow the story with ease.

Additive language, a key feature of orality, is an avoidance of complex sentences. This is clearly relevant for English language learners, for complex sentences, which contain subordinate clauses, are difficult for novices to master. Expert children’s literature authors often make use of the additive characteristic of oral tales, such as multiple ‘ands’ or polysyndeton. Used in close sequence, polysyndeton can generate intensity and determination. This is shown in the following extract from Philip Pullman’s The Firework-Maker’s Daughter (1995), in which the protagonist, Lila, is determined to climb up a volcano:

And her throat was parched and her lungs were panting in the hot thin air, and she fell to her knees and clung with trembling fingers as the stones began to roll under her again. […] She dragged herself on bleeding knees up and up, until every muscle hurt, until she had no breath left in her lungs, until she thought she was going to die; and still she went on. (p. 69)

With this urgent and intense writing, we are made to feel with Lila how the painful ascent of Mount Merapi batters and burns her throat, knees, and fingers. Polysyndeton, the repetition of conjunctions, is a rhetorical device that young children often use in their own storytelling. Here, it emphasizes the inexorable painfulness of the climb: And her throat / and her lungs / and she fell / and clung. Finally, the three-fold repetition of until in the last sentence relentlessly builds up to the climax ‘and still she went on’, illustrating the power of the rhetorical rule of three.

Rhetorical anaphora is a poetic device that creates rhythm and emphasis by repeating words or word sequences at the beginning of neighbouring sentences in prose, or the beginning of lines in poetry. In The Savage (Almond, 2008), the narrator, Blue, emphasizes the closeness between himself and the savage he creates by his use of rhetorical anaphora (repetition of I could…): ‘When I drew him and wrote about him, I could see him, I could hear him, I could smell him. Sometimes, it was nearly like I was him and he was me’ (p. 31).

The poetic play of repetition and anaphora, and other stylistic elements that create cohesion, can be illustrated by Almond and McKean’s (2013, unpaginated) Mouse Bird Snake Wolf. This is a mystical tale about mankind’s creative power, but with a dangerous edge that is highly topical: that destruction, perhaps even evil, will follow hubristic anthropocentric creativity. Can anything be done to rid the world of a perilous thing once it has been created? The book begins: ‘Long ago and far away’, and it tells of a world not quite finished. The gods who created this world became complacent and inept, so one day, three children, Little Ben, Sue, and Harry, inspired to creativity themselves, invent some missing animals: a mouse, a bird, a snake, and a wolf. While the language seems simple in the style of an oral tale, it illustrates the suggestiveness of rhythmical repetition and storytelling rich in sensory imagery. Little Ben begins by creating a mouse: ‘The mouse tottered to its tiny feet; it sniffed the air; it peeped into the sky with its little bright eyes. It squeaked, and squeaked again, and squeaked again, and scampered right away.’ All at once ambitious, Harry, an older boy, becomes creative and conjures a twisty, legless thing: ‘And yes! The snake hissed. It lifted its head and it hissed again. It slithered towards them across the grass. Its scales glittered. Its eyes gleamed. It bared its sharp little teeth. It flicked its forked little tongue.’ We can truly hear the snake’s hissing, which makes for an impressive first meeting.

Little Ben, Sue and Harry are thrilled at their success, and, having invented a mouse, a bird and a snake, they become more audacious, ‘They stood up straight and they stared across the earth and they stared into their minds and they searched their thoughts and they searched their dreams and they wondered.’ The alliteration – repetition of ‘s’ – seems to underline their searching for ideas. Suddenly, they decide to create a wolf. Inventing a wolf in what seems to be a fairy tale is likely to be a risky undertaking – this is a hauntingly illustrated tale on the hope, the beauty, and the danger of creativity. Almond uses anaphora to emphasize the inevitability of the peril:

And yes, the wolf stirred!

And yes, it stood up!

And yes, it howled up!

And yes, it ran!

It howled and it ran straight at Harry and Sue…

Setting and sensory imagery

For the reader to be able to visualize characters and the setting, novice writers need to focus on providing sensory details, so that we can experience the setting and engage with the characters in a multisensory way, recreating scenes the writer evokes bodily in our perceptions, our emotions, and thoughts. Karen Coats (2013) suggests that the songs and poetry that adults share with infants can fundamentally bring ‘the two planes of our existence – sensory experience and conceptual language – together as one’ (p. 135). Through this learning and communicative musicality, we discover not only how to share a vision, but also achieve that others may ‘do something more profound than merely understand, but actually re-experience that vision’ (p. 135). Coats writes of feeling with and connecting to others through poetic texts:

Sometimes that connection is through a message that is communicated by the words of a poem, but sometimes the connection is not message-driven at all but rather an experience of emotional attunement. Rhythm is contagious, rhyme is predictable, and the result is that children’s poetry is almost irresistibly participatory. (p. 137)

Myhill (2020) refers to a weakness in secondary school writing as ‘over-emphasis on plot, resulting in plot-driven narratives with much weaker characterisation, and establishment of setting’ (p. 204). This over-emphasis on plot might be due to the long-established concept of a dramatic arc, with an introduction followed by tense rising action, leading to a climax or turning point, with problems then ensuing and a suspenseful reversal, foreshadowing the final catastrophe (or a hopeful, promising resolution). However, this classic plot structure (Freytag, 1863/1905, p. 102) was meant to describe a five-act play (or potentially a three-act play); it is far less relevant for students’ narrative creative writing. Resources found on the internet are often misleading too – if teachers use search machines to find guidance on ‘How to organise a story in English’ or ‘Narrative writing step by step’, for example, they will find outlines that look easy to follow, but that completely ignore the painstaking craft aspect of writing, and poetic word choices, which can best be exemplified by works of expert writers (and not by simplistic schemes).

Pullman’s writing can powerfully illustrate the central role of sensory imagery in creating settings. In The Firework-Maker’s Daughter, Pullman (1995) evokes a vivid backdrop for Lila, the young girl who wishes to become a firework-maker:

All the jungle sounds, the clicking and buzzing of the insects, the cries of the birds and monkeys, the drip of water off the leaves, the croaking of the little frogs, were behind her now. […] now there was nothing except the sound of her foot on the path and the occasional rumble from the mountain, which was so deep that she felt it through her feet as much as she heard it through her ears. (p. 64)

As students read this passage, they can reflect on the sensory imagery – how they can visualize the insects, birds, monkeys, and frogs, hear the noises they make, feel the drips of water on their skin and the threatening rumble of the volcano reverberating through their frame.

Clockwork is another short chapter book by Pullman (1996). It is particularly suitable for dark winter months, when the teacher could make a formidable impression by reading aloud some of the enigmatic and eery chapters in a shadowy classroom, lit only by candlelight, rather like tales around a wintry campfire. The setting of Clockwork is again established with rich sensory imagery:

It began on a winter’s evening, when the townsfolk were gathering in the White Horse Tavern. The snow was blowing down from the mountains, and the wind was making the bells shift restlessly in the church tower. The windows were steamed up, the stove was blazing brightly, Putzi the old black cat was snoozing on the hearth; and the air was full of the rich smells of sausage and sauerkraut, of tobacco and beer. (pp. 11–12)

A creative task can be for students to try to emulate the generation of sense impressions of Pullman’s settings – of sight, sound, movement, touch, taste, and smell – in their own creative writing, especially when crafting the beginning of a story and establishing the setting. Below is an example of a student teacher’s response to the task: ‘Write the beginning of a new story (one or two paragraphs), inspired by Pullman’s opening of Clockwork.’ The student’s work includes varied sensory imagery and carefully maintained connectivity:

It began in the Norwegian fall, a Sunday around noon […] The smell of hot chocolate and lukewarm cinnamon buns drifted through the wind. The wind was beginning to get cold and was so powerful that it had almost stripped the trees of leaves. The orange and brown leaves were collected in piles, and you could hear the children’s laughter miles away when they jumped in them, spreading the leaves around the nearby neighbourhood. The neighbourhood where everyone was at home snuggling under cosy blankets, with Netflix on and the candles lit. Just going by, you could feel the warmth and happiness from inside, and sense the smell of lamb and cabbage stew heating up.

Phonological patterns

Phonological rhetorical devices include alliteration, assonance, cacophony, onomatopoeia and, of course, rhythmical patterns, which can make reading and listening more compelling as the sound extends the sense. Cacophony describes word choices to create a discordant, chaotic, and perhaps riotous situation by using jarring, explosive words. In Almond’s stage play (2002), Wild Girl, Wild Boy, the voices of schoolmates, teachers or neighbours are often used as a chorus, to comment on the action, but also to deride, taunt and bully the young protagonist, Elaine. The following chorus scene illustrates Almond’s use of cacophony:

THE CHORUS OF VOICES

– She’s crackers, of course.

– Really crackers. Right round the twist.

– Have you heard her? Howling and yowling.

– Chanting and ranting.

– Making a noise fit to wake the dead. […]

– See her dancing like a loony.

– See her banging on the windows.

– Hear her yelling, Let me out!

– Let me out!

– Let me out! (p. 61)

Rhythm is a fundamental feature of dance and music as well as language, and participation can provide a shared social experience, and a sense of wellbeing, for all age groups. Any topic can be rapped, and adding a catchy rhythm and movement to a message is likely to create potent multisensory learning in language education. Raps are recited rapidly, echoing features of poetry, and performed over a rhythmical instrumental backing, echoing dance and song. A rap is a prose-like poetic format intensifying the natural rhythms of spoken language to create an insistent pattern – a 4/4 time signature – that needs to be heard in performance, as the rhythmic delivery by the rapper and strongly rhythmic accompaniment are key features. Rap energizes through its embodied rhythms and dynamic but chant-like performance, including rhyme that may be multisyllabic, and a strong metronomic beat, to create a flowing delivery.

According to Derek Attridge (1995), the metrical structure of rap consists of lines with four stressed beats,

separated by other syllables that may vary in number and may include other stressed syllables. The strong beat of the accompaniment coincides with the stressed beats of the verse, and the rapper organizes the rhythms of the intervening syllables to provide variety and surprise. (p. 90)

A rap as mentor text could be the impressive three-minute ‘Save the Planet’ song, created by Wonder Raps (MC Grammar, 2021), which is available on YouTube (https://tinyurl.com/m56n7ysz). If student groups create their own raps, the remainder of the class could easily supply the regular backing rhythm. Alternatively, students could film their raps to backing music and show the recorded performance in class.

Creative writing, Jane Spiro claims (2004), ‘is for teachers who wish to add a sense of production, excitement, and performance to the language classroom, to give students the opportunity to say something surprising and original, even while they practice new aspects of language’ (p. 5). According to Spiro, creative writing activities will help students ‘develop an appreciation of the sounds and rhythms of language, sentence patterns, the shape and meaning of words, how words and sentences connect with one another to form texts, and the features of different text types’ (p. 10). All of these, Spiro points out, are skills that the confident reader has a good chance to develop.

Characterization

Being able to appreciate, and perhaps also create and write convincing characters, may help students relate to literary texts, as the ability to empathize with characters, emotionally connecting to another and tangible perspective-taking, is essential for literary engagement. Michael Toolan argues (2014) that in a narrative storyworld characters are expected to be self-consistent physically and mentally as well as emotionally: ‘character is perhaps the most striking domain in which coherence within the storyworld normally needs to be protected by the author’ (p. 73). Brown et al. (2019) have coined a new term, protagonism, as their study has revealed that character interaction and psychological dynamics are central to contemporary story. Protagonism refers to the phenomenon that narrative is typically character-driven and not (as often supposed) primarily plot-driven – stories are mediated by the characters, and their emotions and experiences are the driving force. Previously, Noam Chomsky (1988) had already surmised that psychological dynamics and complex characters drive the plot of a story, rather than vice versa:

it is quite possible – overwhelmingly probable, one might guess – that we will always learn more about human life and human personality from novels than from scientific psychology. The science-forming capacity is only one facet of our mental endowment. We use it where we can but are not restricted to it, fortunately. (p. 159)

With this in mind, we can consider interpreting and understanding character to be an essential exercise in interculturality (see, for example, Bland, 2020) – seeing and respecting other perspectives – as well as critical for the development of literary literacy.

A significant moment in the development of a characterization is often when the figure is first introduced. In Wild Girl, Wild Boy (Almond, 2002), the wild girl Elaine fears a character named McNamara, who tends to carve everything into rigid categories. Elaine, on the other hand, has had poetic, dream-like and magical experiences with her father and now, following his death, seems to have lost her way. With very few carefully chosen words and images, expressed by the characters in the play, first Dad, then the character of McNamara, are skilfully created:

DAD A lark’s egg. See? Speckled white outside. And brilliant white inside. A chick came out from this. Can you believe it? A little chick made from a yellow yolk and a salty white that’ll one day soon be flying over us and singing the loveliest of songs. A miracle. Look! Larks, larks, larks. (p. 18)

ELAINE McNamara. Had the allotment next to Dad’s. Beady eyes, beady stare. Always watching us, he was, always sneering at us. His place was all neat and trim with peas and beans and onions in neat trim rows. (p. 21)

Both of these brief portrayals include ellipsis – words such as subject pronouns are missing, so emphasizing key ideas by jettisoning redundant, unnecessary words, and some sentences are incomplete, which also tends to intensify meanings by omitting dispensable words. Fragmentary utterances that lack a finite verb can be found everywhere in masterful creative writing, even though this is not normally acceptable in more formal writing, such as this article. Used perceptively (students should read their own texts aloud and attend closely to its sound and rhythm), fragmentary utterances and ellipsis can help create a pleasing percussion effect and further focus and accentuate meanings. However, the above characterizations strongly differ in the lexical choices – Dad’s wonder at the miracle of life is suggested by a lexical chain around birds (lark’s egg, chick, yellow yolk, salty white, flying, singing) whereas Elaine uses a lexical chain that implies McNamara glowers with suspicion at others (beady eyes, staring, watching, sneering), and the repetition of neat and trim reinforces his dissimilarity to Dad. This is carefully crafted but can seem visceral; as Coats writes (2013), ‘poetic language shapes our world, enchants it with patterned sound and metaphors that link our bodies to the world around us’ (p. 134).

Students can be asked to write a memorable first meeting with a character. Here is a student teacher’s characterization of the wolf on its first appearance in Mouse Bird Snake Wolf. The portrayal illustrates how sensory imagery can enable the reader to see, smell and feel the fear and horror the wolf inspires:

A wolf, a predator that could have been plucked from the darkest corners of children’s nightmares. This horror wore a coat as dark as the deepest night, swirling and twisting like a tempest. The monster’s scent danced through the air, its odour a kind to fear. […] Its presence was not just a tale told to children; it was a living, breathing embodiment of terror itself.

A very simple but thoughtful creative writing task, which gives students the opportunity to reflect on character, is the acrostic. This is a composition around a single word or name, which is spelled out by the first letter of each line. The following examples show acrostics student teachers have written on characters from Clockwork (Pullman, 1996). The characters’ names (Otto and Dr Kalmenius) are read vertically:

Demonic in his ways

Roams into the bar during Fritz’s story

Keen on helping Prince Otto make his son from clockwork

All of his clockworks fail, almost like they died

Lingering dark and ominous presence

Mysterious and creepy

Eludes all intentions

Not to be trusted

Immoral in his actions

Unemotional

Speaks in riddles.

Out of his mind with fury

Trying his best to save his heir

Traded his heart for his son’s life

Overcome by the love of his son.

Variation

While poetic-repetitive patterns are important in creative writing, so is variation. This includes innovative metaphors and lexical expressions as well as variation in style. Geoff Hall (2018) writes, ‘variation is the most basic characteristic of language use in literature and a wider range of variation is typically found in literary texts than in any other text type or [discourse] genre’ (p. 266). Toolan (2012) writes of the ‘urge to hybridize’ (p. 18) and the breaking of rules regarding format and literary genre, offering new opportunities for originality in creating innovative texts. We see this in two of Almond’s texts quoted in this article, for The Savage and Mouse Bird Snake Wolf are both extremely difficult to fit into current categorizations of literary format.

Novice creative writers can be challenged to give rhythm to their writing by varying the tempo; flashes of brevity should be juxtaposed with lengthier, imagery-rich detail. Gary Provost (2019) illustrates the power that variation of sentence length can have to enliven writing, to slow down or accelerate the pace:

This sentence has five words. Here are five more words. Five-word sentences are fine. But several together become monotonous. Listen to what is happening. The writing is getting boring. The sound of it drones. It’s like a stuck record. The ear demands some variety.

Now listen. I vary the sentence length, and I create music. Music. The writing sings. It has a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony. I use short sentences. And I use sentences of medium length. And sometimes when I am certain the reader is rested, I will engage him with a sentence of considerable length, a sentence that burns with energy and builds with all the impetus of a crescendo, the roll of the drums, the crash of the cymbals – sounds that say listen to this, it is important. (pp. 60–61)

This is persuasive advice on varying sentence length, and it holds true for academic writing as well as creative writing.

Typographic creativity refers to the playful use of typography, often used in comics and picturebooks and increasingly in chapter books, which may intensify or add to the meaning of the printed words. Alternating distinctive typefaces can distinguish the words or thoughts of different characters, while font variations in thickness, size and obliqueness can be used to signify importance, emotion, or tone of voice. Books for young readers have recently become very rich in typographic creativity, using assorted typefaces and fonts, and often hand-written lettering, blurring the distinction between illustration and verbal text. Words may dance off the horizontal lines and there may be a creative use of marks such as dots and asterisks. In this way, typographic creativity carries meaning, such as when the desperation of Little Ben’s attempt to rescue Harry and Sue from the terrifying wolf in Mouse Bird Snake Wolf is indicated by a five-fold repetition of ‘Turn back again, wolf’, first in italics, then in capital letters of ever-increasing size.

In his research on Swedish adolescents who write creatively in English outside of their English lessons, Morris (2022) uses the term outlandish ‘to describe the imaginative and even bizarre stories, or story elements, created by some participants’ (p. 121), and derives the pedagogical implication from his study that, for many school students, opportunities for ‘outlandishness and vivid imagination are most welcome’ (p. 144). According to Morris’s research, adolescents – just as much as children – derive enjoyment and satisfaction from challenge, and ‘this tension between seriousness and play, or imagination and realism, or outlandishness and our lives’ (p. 134). The inclination for outrageousness and playful silliness is foreshadowed in young children who react with such pleasure to their nursery rhymes and ‘the kinesthetic bounce of repetition and surprise’ (Coats, 2013, p. 133). The concept of outlandishness seems to recall Hunt’s (2010) childist approach to children’s literature, and Nikolajeva’s (2010) suggested rejection of aetonormativity, or adult normativity, in that both literature for the young and creative writing may encourage an openness of mind as well as tolerance of ambiguity, an important personality trait to promote for both language and literature learning. Teachers (and student teachers) often believe they should provide answers to all questions (Reynolds, 2017), but understanding literature reading as social practice teaches us that dialogic learning is vastly more productive than single-stance answers. Moreover, schema refreshment, which might be considered the essence of literary worth, relies on the reader’s openness to enlightening, often outlandish surprise.

Developing Creative Writing Tasks for School Students

In the 8-hour unit, I first set out to increase student teachers’ confidence in their own writing competence, by trialling, also as group work, the five key areas as I introduce them in class. Longer tasks, aiming to consolidate the key strategies, are completed at home. I find all students manage some successful examples of creative writing. I am creatively flexible in defining ‘successful’ (for example achieving a satisfying impact on the reader/listener), as a central goal is the writer’s increase in self-confidence and self-efficacy and, ideally, tolerance of ambiguity. Student teachers are invited to read one or other of their favourite pieces aloud in class – this provides an opportunity for peer feedback as well as important read-aloud practice for on-going teachers. Student teachers usually need practice in developing their teacher’s voice, which entails learning to read aloud clearly and at a slightly slower tempo, emphasizing the rhythm, while maintaining eye contact with their audience (see Bland 2022, p. 288, for a definition of ‘creative teacher talk’).

In a next step, I give the student teachers the assignment to design creative writing tasks based on a mentor text that all have read, which I also used to illustrate the key strategies. A mentor text should be a work of children’s fiction, for when student teachers are able to try out their tasks in their school teaching practice they are likely to receive ideal feedback on their ideas – from the children themselves. Pullman’s Clockwork offers many opportunities for creative response, which might be suitable for 8th and 9th grade students in Norway (13- to 15-year-old students), who have been learning English since primary school. The following tasks are some of the motivating ideas fashioned by Norwegian student teachers:

- Use your imagination to describe mysterious Dr Kalmenius’s workshop. Remember that he is a clever man, a ‘philosopher of the night’ (Pullman, 1996, p. 27), and a marvellous clockmaker who can make just about anything with clockwork. Describe how it looks, what you can see, smell, hear, and how you feel when you’re walking around in the workshop. Focus on your descriptive words to create a picture of what you experience in the workshop.

- Create a crime board featuring one of the crimes in the story. Describe where the crime takes place, and include a map, the murder weapon, and some of the main characters. Mark the characters as victim, suspect(s), and witness(es). (See Figure 1 for a student teacher’s crime board based on Clockwork.)

Figure 1. Student teacher’s Crime Board based on Clockwork

- Create a comic strip (pictures that together tell a story) of a scene in Clockwork that stood out for you. Create one strip with at least three panels telling the story of the moment you have chosen. Use literary devices that are typical for comics, like onomatopoeia, speech and thought balloons. Scenes you could use: Fritz’s story, Dr Kalmenius creating Prince Florian, Karl’s death, Gretl saving Prince Florian, or choose another scene.

- Write a short story with Putzi as the narrator and the main character. Try to put your head inside Putzi, and describe the cat’s thoughts and feelings in a scene from the book, for example in the clocktower watching Karl carrying Prince Florian, or outside the inn listening to Fritz telling his story.

- Imagine you were the apprentice of Herr Ringelmann, the clockmaker. Draw a picture of the figure you would create for the clock of Glockenheim and then describe it in detail. What does it do once it is wound up and displayed as the hour strikes?

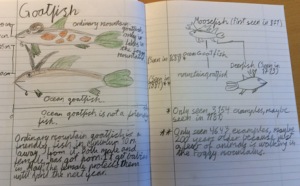

Ideally, teachers use their inventiveness to develop tasks to respect and exploit the imagination of young creative writers, while encouraging the use of the key strategies. The following examples illustrate the potential of Almond and McKean’s Mouse Bird Snake Wolf (2013). These are likely to be suitable for 5th to 7th grade students in Norway (10- to 13-year-olds):

- Can you invent an amazing animal for a new Weird World? Decide how you want to name your creature and write a detailed description. Where does the creature live? What does it like to eat? Is it friendly? Is it endangered? Make sure to illustrate your amazing animal. (See Figures 2 and 3 for examples from a 5th grade English class.)

- In Mouse Bird Snake Wolf, the gods do little – they sip tea, they lay on their clouds, they nibble sandwiches and cakes, they chat about their creations, they sleep and snore. Discuss, imagine, and write down what else the gods might do, and describe their setting, while the story of Little Ben, Sue and Harry evolves.

- The wolf in Mouse Bird Snake Wolf is scary. In Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Harry is taught how to transform a terrifying boggart (a shapeshifter that portrays the beholder’s worst fear) into something funny. Create a description and illustration of what you would transform the wolf into if you had the magic to do so.

- What was the wolf’s backstory? Why did she turn ferocious? Write half a page about the wolf’s previous experiences, including a shocking event which led to her turning savage. Feel free to draw the wolf as well.

Figure 2. Weird World: Meet amazing animals!

Figure 3. Weird World: Meet goatfish and moosefish

Concluding Remarks

I have found that even brief training in creative writing strategies, with circa eight hours dedicated to this in teacher education, can considerably increase confidence among student teachers both in their own creative writing competence and in their designing creative writing tasks for school students learning English. Observing some of my student teachers during their teaching practice in Norway, I could witness their enthusiasm for working with creative writing in the lessons they designed. However, I find student teachers need reminding to focus on building confidence first with small, carefully planned steps when including creative writing in their teaching. There is always the danger that language learners will focus too much on plot events and dialogue, which they tend to believe is easier. But neither writing dialogues, nor writing summaries, will practise the key strategies of narrative as outlined in this article as a useful foundation for creative writing. I find the shared reading of a well-chosen mentor text, as put forward in this article, is an important part of creative writing guidance.

Spending time on creative writing in English language education, teachers give their students a reason to invest thoughtfulness, personal significance, and feelings in their writing, awakening intrinsic motivation, and aspiration to write well. Creative writing tasks can help school students to write effectively, to take care in their language choices and pride in their work. The processes of creative writing include students exchanging their ideas with peers, crafting a first version, then editing, polishing, attending to layout and presentation, editing again and finally sharing. Students’ carefully crafted creative writing could be kept as individual collections, as a class anthology or as part of a school online presence. Creative texts may be displayed on the wall or performed in the classroom and at school events, with potentially considerable increases in resultative motivation and self-efficacy. This might reverse the current trend, influenced by social media communication, that encourages students to understand writing as a fleeting activity.

A systematic review of teachers as writers (Cremin & Oliver, 2017) indicates ‘fossilised notions of authorised writing’ (p. 292), and, moreover,

that teachers have narrow conceptions of what counts as writing and being a writer and that multiple tensions exist. These relate to low self-confidence, negative writing histories, and the challenge of composing and enacting the positions of teacher and writer in the classroom. This suggests that for many teachers, the teaching of writing is experienced as problematic. (pp. 291-2)

Fortunately, I have observed that most student teachers, when they focus on the key strategies, are able to increase both their skill and their confidence in writing, although it is more difficult to discern an increase in tolerance of ambiguity with such a brief teaching unit. Similarly, it is difficult to claim that creative writing tuition with student teachers has a lateral effect of increase in competence for academic writing, which has very different conventions and aims. Still, the observable growth of student teachers’ confidence in their written work is likely to be transferable to academic writing. Moreover, academic reading (and the reading and understanding of any verbal text) undoubtedly profits from an ability to sense the stance of the author through increased attention to how meaning-making processes can be channelled (and sometimes indeed manipulated) through, for example, the rhetorical devices of repetition, sensory imagery, and stylistic cohesion.

Bibliography

Almond, David (2002). Wild Girl, Wild Boy. Hodder Children’s Books.

Almond, David, illus. Dave McKean (2008). The Savage. Walker Books.

Almond, David, illus. Dave McKean (2013). Mouse Bird Snake Wolf. Candlewick Press.

MC Grammar (2021, October 29). Save the Planet [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FreR7ZhqRQQ

Pullman, Philip (1995). The Firework-Maker’s Daughter. Corgi Yearling Books.

Pullman, Philip (1996). Clockwork. Doubleday.

References

Attridge, D. (1995). Poetic rhythm: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Baron, N. S. (2015). Words onscreen: The fate of reading in a digital world. Oxford University Press.

Bland, J. 2020. Using literature for intercultural learning in English language education. In M. Dypedahl, & R. Lund (Eds.), Teaching and learning English interculturally (pp. 69–89). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Bland, J. (2022). Compelling stories for English language learners. Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy. Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350190016

Bradford, C., McCallum, R., Mallan, K., & Stephens, J. (2007). New world orders in contemporary children’s literature. Utopian transformations. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230582583

Brown, S., Berry, M., Dawes, E., Hughes, A., & Tu, C. (2019). Character mediation of story generation via protagonist insertion. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 31(1), 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2019.1624367

Chomsky, N. (1988). The view beyond: Prospects for the study of mind. In N. Chomsky (Ed.), Language and problems of knowledge. The Managua lectures (pp. 133–170). MIT Press.

Coats, K. (2013). The meaning of children’s poetry: A cognitive approach. International Research in Children’s Literature, 6(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.3366/ircl.2013.0094

Cook, G. (2000). Language play, language learning. Oxford University Press.

Cremin, T., & Oliver, L. (2017). Teachers as writers: A systematic review. Research Papers in Education, 32(3), 269–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1187664

Crystal, D. (1998). Language play. Penguin Books.

Crystal, D. (2004). Rediscover grammar. Longman.

Cummins, J., Hu, S., Markus, P., & Montero, M. K. (2015). Identity texts and academic achievement: Connecting the dots in multilingual school contexts. TESOL Quarterly, 49(3), 555–581. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.241

Deszcz-Tryhubczak, J. (2016). Yes to solidarity. No to oppression. Radical fantasy fiction and its young readers. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego.

Gallagher, K. (2014). Making the most of mentor texts. Educational Leadership, 71(7), 28–33.

Freytag, G. (1863/1905). Die Technik des Dramas (10th ed.). S. Hirzel Verlag https://www.gutenberg.org/files/50616/50616-h/50616-h.htm

Hall, G. (2018). Literature and the English language. In P. Seargeant, A. Hewings, & S. Pihlaja (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English languages studies (pp. 265–279). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351001724-19

Hunt, P. (2010). Confronting the Snark: The non-theory of children’s poetry. In M. Styles, L. Joy, & D. Whitley (Eds.), Poetry and childhood (pp. 17–23). Trentham Books.

Leland, C., Lewison, M., & Harste, J. (2013). Teaching children’s literature: It’s critical! Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203125311

Lutzker, P. (2015). The complementary roles of literature and creative writing in foreign language learning. Humanising Language Teaching, 17(2). http://old.hltmag.co.uk/apr15/mart04.htm

Maley, A. (2013). Creative writing for L2 students and teachers. In J. Bland, & C. Lütge (Eds.), Children’s literature in second language education (pp. 161–172). Bloomsbury.

Morris, P. (2022). Creative writers in a digital age. Swedish teenagers’ insights into their extramural English writing and the school subject of English. Mälardalen University. http://mdh.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1611856&dswid=-2391

Morris, P. (2023). ‘Oh, Hello Word!’ Boundary crossing between Swedish and English. Changing English, 30(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2023.2202304

Moses, L. (2014). What do you do with hands like these? Close reading facilitates exploration and text creation. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 2(1), 44–56. https://clelejournal.org/what-do-you-do-with-hands-like-these/

Myhill, D. (2020). Wordsmiths and sentence-shapers. Linguistic and metalinguistic development in secondary writers. In H. Chen, D. Myhill, & H. Lewis (Eds.), Developing writers across the primary and secondary years: Growing into writing (pp. 194–211). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018858-11

Myhill, D., Lines, H., & Jones, S. M. (2018). Texts that teach: Examining the efficacy of using texts as models. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 18, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.17239/L1ESLL-2018.18.03.07

Nikolajeva, M. (2010). Power, voice and subjectivity in literature for young readers. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203866924

Nikolajeva, M. (2014). Reading for learning: Cognitive approaches to children’s literature. John Benjamins.

Ong, W. (2002). Orality and literacy (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203426258

Oziewicz, M. (2015). Justice in young adult speculative fiction: A cognitive reading. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315749907

Provost, G. (2019). 100 ways to improve your writing (updated ed.). Berkley.

Read, C. (2015). Seven pillars of creativity in primary ELT. In A. Maley, & N. Peachey (Eds.), Creativity in the English language classroom (pp. 29–36). British Council.

Reynolds, D. W. (2017). ‘Teachers want to know answers to questions’: Dudley Reynolds on teacher research, interviewed by Daniel Xerri. ETAS Journal, 34(3), 12–13.

Reynolds, K. (2007). Radical children’s literature: Future visions and aesthetic transformations in juvenile fiction. Macmillan.

Russell, C. (2018). Free play revisited. The poetics of repetition in Blake’s Songs of Innocence. In K. Wakely-Mulroney, & L. Joy (Eds.), The aesthetics of children’s poetry (pp. 47–58). Routledge.

Simpson, A., & Cremin, T. (2022). Responsible reading: Children’s literature and social justice. Education Sciences, 12(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12040264

Spiro, J. (2004). Creative poetry writing. Oxford University Press.

Toolan, M. (2012). Poems: Wonderfully repetitive. In R. Jones (Ed.), Discourse and creativity (pp. 17–34). Pearson.

Toolan, M. (2014). Coherence. In P. Hühn, J. C. Meister, J. Pier, & W. Schmid (Eds.), Handbook of narratology (2nd ed., pp. 65–83). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110316469.65