JAPAN • The economic development of post-war Japan has been supported by people working long hours, submitting to job relocation and rarely refusing to travel for business.

It is difficult to combine such a work culture with family life.

Karoshi (death from overwork) and companies that overwork their employees have become real problems for society.

According to a report last year by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Japan's productivity ranked the lowest among the Group of Seven nations, well below the average.

With the working population decreasing due to a decline in birth rate and an increase in the number of elderly, there is a widespread labour shortage that has affected even the service industry. Many enterprises have been forced to shorten business hours due to a lack of workers.

One might think that working less leads to lower profits. But in Hadano, Kanagawa prefecture, one ryokan (traditional Japanese inn) managed to double its profits despite closing its doors three days a week. The average annual salary of its workers grew by 40 per cent.

-

3

-

Number of days a week that Jinya inn is closed. Yet, profits have doubled.

The Jinya inn's watershed moment came after the sudden death of its owner in 2009. His eldest son Tomio Miyazaki, now 40, left his job as an engineer with a major automaker to take over the business. His wife Tomoko, also 40, became its manager just two months after giving birth, even though she had never worked in a ryokan before.

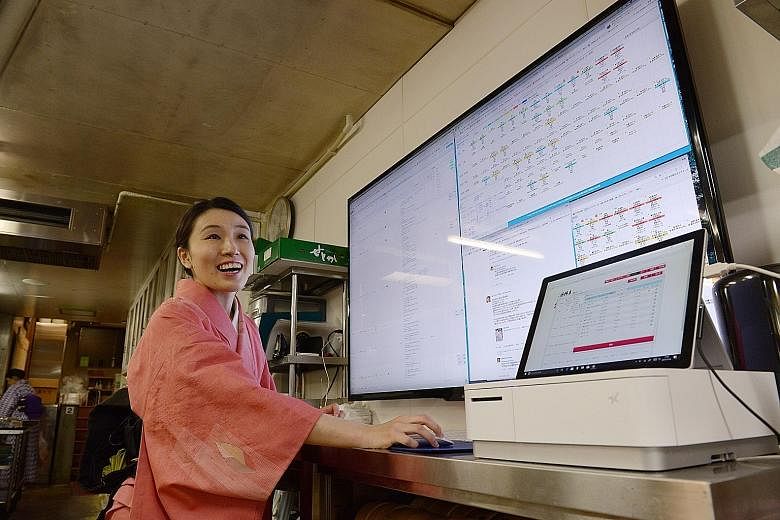

They found the inn had debts of one billion yen (S$12.2 million) due to mismanagement and excessive waste. Turning to information technology as the solution to the problems, they developed software to manage and standardise a range of tasks, from reservations to accounting.

The couple distributed tablets to all staff members so that they could share information, such as customer preferences, to improve customer service.

They also installed sensors in the communal bath, notifying employees when the number of customers exceeded a certain cut-off. Staff members no longer had to visit the bath repeatedly to check whether it needed cleaning.

The couple reduced wasteful working practices, and channelled their employees' energies towards creating better meals and other selling points. They gradually raised room rates, and created an extra revenue stream by selling the management system to other inns.

Business improved but at the same time, a new problem emerged - Mrs Miyazaki was exhausted from working non-stop.

"Even if customer satisfaction rises, it is meaningless if the workers' quality of life does not improve too," she said.

In 2014, the couple made the radical move to close the inn every Tuesday and Wednesday. They went further in 2016, deciding to close after lunch on Mondays and to stop taking overnight guests that day.

Despite the changes, total annual sales for the inn and its group of companies increased from 290 million yen in 2010 to 726 million yen today. Workers' annual average incomes increased from 2.88 million yen to 3.98 million yen, while employee turnover dropped from 33 per cent to 4 per cent.

"I want to promote a way of working that can accommodate different stages of life, such as child-rearing and nursing care, for the entire industry," Mrs Miyazaki said. "I'm aiming to make inns an industry in which people long to work."