An evaluation of a professional development program aimed at empowering teachers’ agency for social justice

- 1School of Education, HAN University of Applied Sciences, Nijmegen, Netherlands

- 2Fontys School of Teacher Training for Educational Needs, Fontys University of Applied Sciences, Tilburg, Netherlands

- 3Behavioural Science Institute, Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands

- 4Leiden University, Education and Child Studies, Leiden, Netherlands

This article reports on an evaluation study of a professional development program to promote teachers’ agency for social justice and educational equality. Despite that teachers are seen as change agents for social justice, few studies have investigated what empowers them to adopt this role. Therefore, we designed a theory of change with seven manifestations of agency for social justice (e.g., being committed and experts, taking initiatives). Fourteen primary school teachers participated, engaging in individual reflections, focus group interviews, and an open-ended questionnaire. Thematic analysis was used to code manifestations of agency such as commitment and initiatives. The results demonstrated an empowered sense of agency among the participants. For example, they displayed heightened awareness of inequalities and a critical stance toward their own actions, school policies, and the education system in relation to educational equality. This study contributes to theoretical knowledge about how a professional development program for experienced teachers can be used to develop agency for social justice. Key factors that supported teachers’ agency included sufficient time and support in the program to familiarize themselves with social justice and educational equality concepts, as well as receiving comprehensive knowledge on practical interventions and dedicated time for discussing their applicability in their own teaching practice.

1 Introduction

In most western societies, schools are considered to be engines for social justice (Autin et al., 2015). Educational equality is fundamental to achieving social justice (Bartell et al., 2019). However, international surveys show that education fails to fulfill this “equalizer” role, as students’ social backgrounds still strongly predict their educational attainment (OECD, 2023). In other words, the ideal of educational equality has not been attained (Autin et al., 2015). There are large gaps between privileged and disadvantaged groups worldwide in terms of educational opportunities and outcomes (Cochran-Smith et al., 2016).

Teachers are the most critical in-school actors because they might apply pedagogical approaches that dismantle the educational environment’s structural inequalities and improve the academic performance of disadvantaged students (Ainscow, 2020; Min et al., 2021). Their choices can and do make a difference in what and how students learn (Hattie, 2009). For example, teachers can choose alternative grouping strategies instead of homogeneous ability grouping, which increases inequalities between students with different social backgrounds (Francis et al., 2019), or they can take collaborative actions to address inequality issues beyond the classroom (Florian and Spratt, 2013). Because of teachers’ potential influence on student achievement, they are being called upon worldwide to become “agents of change,” a call that is often linked to a social justice agenda (Pantić and Florian, 2015; Bartell et al., 2019).

Many studies suggest that, as agents of change, teachers must learn to engage in dialogue and join forces to become social justice advocates and address educational equality (Wang et al., 2017). Engaging in dialogue involves considering social justice concerns and working toward what is good for all children (Pantić and Florian, 2015; Wang et al., 2017; Van Vijfeijken et al., 2021). Despite the general agreement among educational scholars that teachers as change agents play an essential role in pedagogical approaches that promote social justice in their classrooms, few studies have investigated what empowers them to adopt this role (Pantić et al., 2019; Min et al., 2021). There is a pressing need to support teachers’ agency for social justice (e.g., Pantić and Florian, 2015; Min et al., 2021). More specifically, there is little clarity about how agency for social justice can be developed in a professional development program for experienced teachers (Pantić and Florian, 2015; Kauppinen et al., 2020). This study aims to fill this knowledge gap by evaluating a professional development program designed for experienced primary school teachers and examining the elements contributing to teachers’ agency for social justice and educational equality.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Social justice and educational equality

Despite the calls for teachers to act as “change agents” (Fullan, 1993; Van der Heijden et al., 2015; Cochran-Smith et al., 2022) with social justice issues in policies and literature (Pantić and Florian, 2015; Bartell et al., 2019), “social justice” is rarely defined (Grant and Agosto, 2008; Francis et al., 2017; Pantić, 2017). Generally, social justice is associated with distributive justice (Brighouse et al., 2018), which is concerned with the distribution of the conditions and resources that affect individual well-being (Deutsch, 1975; Espinoza, 2007). As for this distribution, social justice is often based on assumptions about fairness (Rawls, 1999). Therefore, distributive justice provides rules or principles people can use to decide whether a practice or outcome is fair (Wright and Boese, 2015).

Two distributive justice principles can be highlighted in the context of education: the principle of equality and the principle of need. Teachers who apply the principle of equality attempt to equally distribute their attention, resources, and options among all students, regardless of their backgrounds (Wright and Boese, 2015; Cropanzano and Molina, 2017). However, applying this principle may lead teachers to neglect the history and social contexts that learners bring to the classroom (Bradbury et al., 2011). Equal treatment in unequal situations is likely to lead to unequal learning opportunities and outcomes (Mijs, 2016). In contrast, teachers who apply the principle of need do not attempt to equally distribute their attention, resources, and options (Wright and Boese, 2015). Instead, students’ needs are linked to their history and social contexts. Students from less educationally supportive backgrounds are considered more in need of education in school settings and thus deserve more support from teachers (Resh and Sabbagh, 2016). This principle contributes to narrowing achievement gaps and is considered fairer for creating equal educational opportunities. However, teachers can perceive unequal distribution of attention and resources as unfair or unjust in educational practice because students from disadvantaged backgrounds benefit from positive discrimination. From different social justice perspectives, teachers can morally justify how they teach students from different social backgrounds. Creating equal educational opportunities calls for need-based teaching practice. However, a need-based distribution of resources will not solve fundamental inequality issues in education because it does not solve the merit-based social inequalities that result from different educational credentials (Sandel, 2020). From a critical social justice perspective, many studies problematize the western meritocratic education system because it legitimates social inequalities as justly deserved, indicating that misfortune is likely to be misunderstood as a personal failure (Sandel, 2020). In a meritocracy, a fair education system leads to unequal social status positions based on individual merit, defined by ability and effort. In such a system, teachers are significant actors in creating social inequalities. Teachers may feel uneasy about this role and could feel they have less agency for social justice.

How can teachers be prepared for their role as change agents for social justice? Given the contentious nature of the term “social justice”, we broadened teachers understanding of social justice with a strong emphasize on social justice as a system of beliefs that underscores principles such as equity and need. The focus of the development program lies in providing high-quality education to all students, irrespective of their race and socioeconomic background. The ultimate objective of social justice oriented education is to address and mitigate the achievement gap that exists between disadvantaged students and their more privileged peers (Miller and Martin, 2015). A professional development program aimed at strengthening agency for social justice not only requires attention to promoting educational equality in the teaching practice but also to structural social inequalities in a meritocratic system (Cochran-Smith et al., 2016).

2.2 Change agents for social justice and educational equality

Studies define “being a change agent” in different ways. However, this term generally suggests that change agents are personally driven to initiate change at both the classroom and school levels by deploying their professional agency (Fullan, 1993; Eteläpelto et al., 2013; Van der Heijden et al., 2015). Professional agency is the willingness and ability to act on professional values, beliefs, goals, and knowledge in teachers’ contexts and situations (Toom et al., 2015). Teaching competencies linked to change agency are broadly conceptualized as encompassing relevant knowledge and understanding as well a capacity to engage with educational change and reflect on one’s beliefs and values (Korthagen, 2004; Pantić and Wubbels, 2010). Preparing teachers as change agents to promote social justice and educational equality requires clarity about what teachers need to know and do, their beliefs, and how they will exercise their agency. Therefore, we used Pantić’s (2015) model of teacher agency, which focuses on teachers’ contributions to greater social justice as the foundation of the professional development program designed for this study. While there is some agreement in the literature about the knowledge, skills and values teachers need to be effective with diverse groups of students (Pantić and Florian, 2015), little is known about how agency for social justice can be developed in a professional development program (Pantić and Florian, 2015; Kauppinen et al., 2020).

This model was based on broader theories of human and professional agency (Giddens, 1984; Archer, 2000) and applied to inclusive teaching practices. The conceptual model articulates potential factors—translated into four domains—that influence teachers’ agency for social justice (Pantić, 2015): (1) a sense of purpose—teachers’ beliefs about their role as agents and understanding of social justice; (2) competence—teachers’ abilities to address the exclusion and underachievement of some students; (3) autonomy—teachers’ perceptions of environments and context-embedded interactions with others; and (4) reflexivity—teachers’ capacity to analyze and evaluate their practices and institutional settings. In addition, the model recognizes that agency depends on structures and cultures (e.g., rules, resources, and power relationships within a school team) and agents can transform these conditions. Finally, agentic teachers can interact intentionally with others as a resource for learning and to support others (Toom et al., 2015).

2.3 Professional development program: change agents for social justice and educational equality

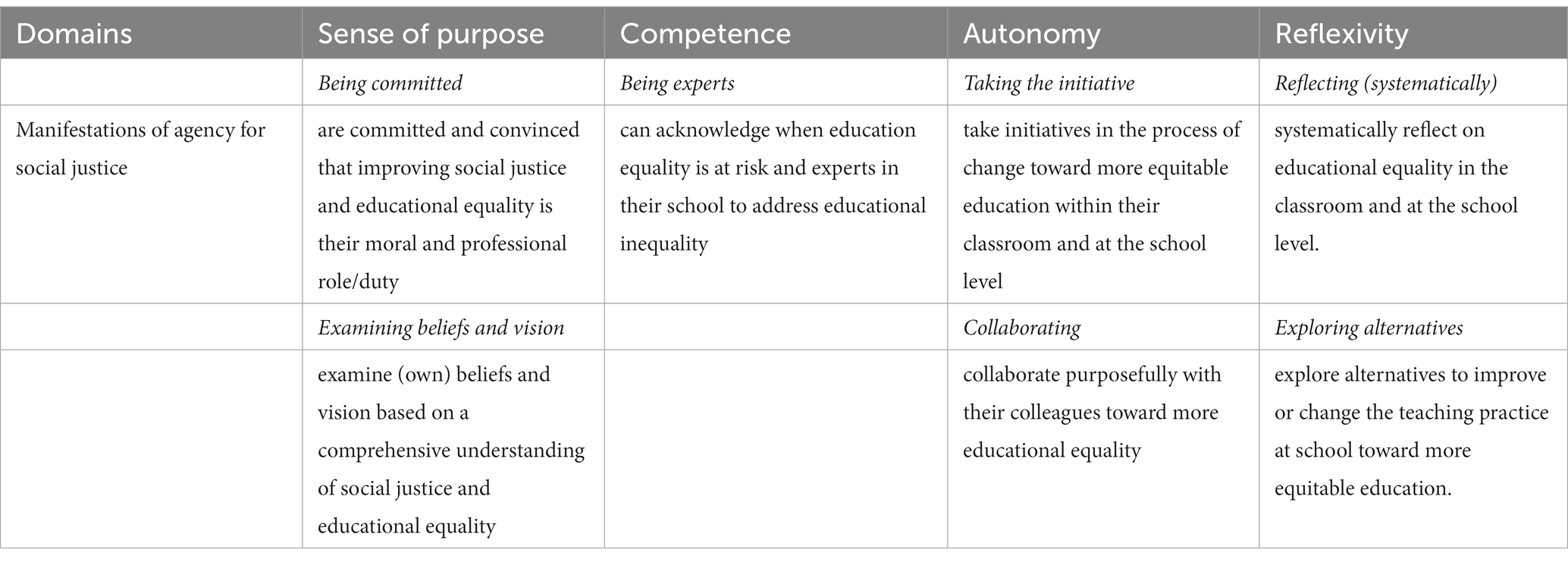

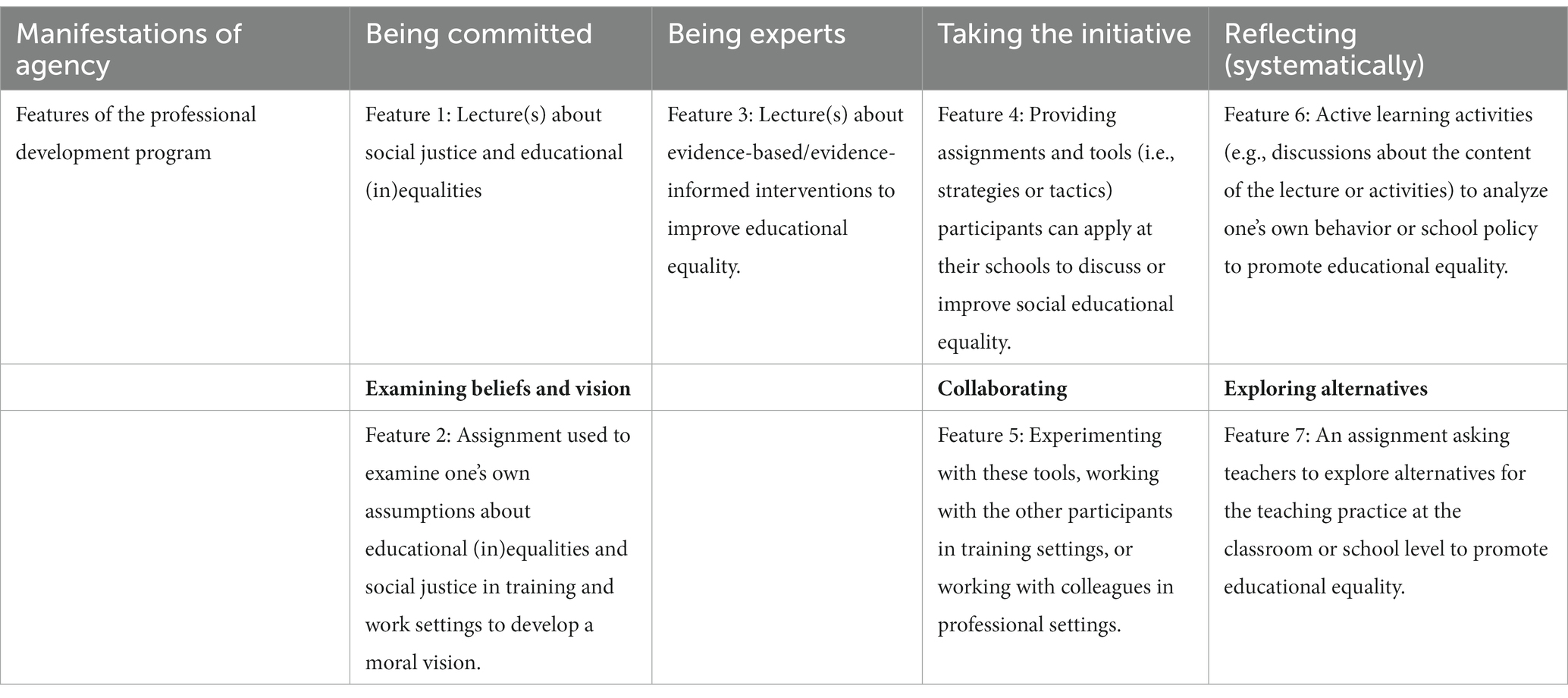

An effective professional development program needs to have a well-defined “theory of change” (Desimone, 2009; Van Veen et al., 2012). A theory of change refers to the assumed relationship between the features of the program and the change in teachers’ behavior. The intended behavior in this study is that participating teachers use their agency to promote educational equality at the classroom and school levels. Each domain in Pantić’s model was used to identify the main manifestations of teachers as change agents for educational equality, and the aim was to empower them through the professional development program (see Table 1).

Each domain is discussed in detail below, including the main manifestations of agency for social justice and the features of the professional development program. In addition, core features of effective professionalization interventions e.g., content focus on classroom practices; evidence-based or evidence-informed content; active learning; collective participation and coherence (e.g., Desimone, 2009; Van Veen et al., 2012) are incorporated into the design of the professional development program. This design led to seven features of the professional development program (see Table 2).

2.3.1 A sense of purpose

A primary assumption in Pantić’s (2015) model is that teachers’ actions as agents for social justice are informed by their commitment and belief that this is part of their professional role. In line with this assumption, Villegas and Lucas (2002) state that teachers as change agents see schools as potential sites for promoting social equality. They commit themselves to social justice or desire to make a difference in students’ lives, and they link their agency to a moral vision (Fullan, 2016). Doing that requires teachers to examine and explicate their own beliefs or vision regarding social justice and educational equality (Pantić et al., 2019; Van Vijfeijken et al., 2023). This might enable them to examine the effectiveness of their school’s practices for promoting educational equality. Some teachers do not prioritize a social justice mandate or work in situations that are receptive to questioning the status quo of educational equality at their school (Bartell et al., 2019). In such cases, teachers might have to take an activist stance. Persisting in their commitment to creating more just educational opportunities for students requires teachers to have significant levels of agency that allow them to create support networks (Bartell et al., 2019). Because of the focus on commitment and one’s own beliefs, this agency domain is strongly linked to the (development of) professional identity by teachers. This is in line with other studies that explicate the relationship between teachers’ sense of agency and professional identity (Bartell et al., 2019).

Concerning this domain, two manifestations of agency were defined for social justice and educational equality (see Table 1). First, change agents for social justice should be committed and convinced that improving social justice and educational equality is their moral and professional duty. Second, they should examine their vision and beliefs based on a comprehensive understanding of social justice and educational equality with their perceived professional role. The professional development program would then involve (see Table 1):

• Lecture(s) about social justice and educational (in)equalities (Feature 1).

• Assignment used to examine one’s own assumptions about educational (in)equalities and social justice in training and work settings to develop a moral vision (Feature 2).

2.3.2 Competence

In the model, competence refers to teaching practice that reflects teachers’ beliefs about their professional skills regarding social justice (Pantić, 2015). Teachers acting as agents for social justice need the proper knowledge and skills to avoid marginalizing students at risk (e.g., students from ethnic minorities or low-educated families, or students who are disadvantaged by poverty). In the United Kingdom and the United States, organizations such as the Education Endowment Foundation, the Leaning Policy Institute, and What Works Clearinghouse provide lists of interventions, programs, and measures that can contribute to equal opportunities and smaller achievement gaps. Comparable overviews are available in the Netherlands (e.g., www.onderwijskennis.eu).

We defined one primary manifestation in this domain (see Table 1). Teachers acting as change agents for social justice should be experts in their schools and have sufficient comprehensive teaching knowledge and skills to address exclusion and underachievement. This expertise is a crucial quality and condition for gaining colleagues’ support for applying initiatives that change education at the school level (Van der Heijden et al., 2015). Furthermore, teachers need the knowledge and skills to be able to acknowledge when educational equality may be at risk. The professional development program would then involve (see Table 2):

• Lecture(s) about evidence-based/evidence-informed interventions to improve educational equality (Feature 3).

2.3.3 Autonomy

Autonomy refers to one’s power within social structures given the levels of autonomy and interdependence with other agents (Giddens, 1984; Archer, 2000; Pantić, 2015). Teachers who want to act as agents of change for social justice need the support of other actors at the school. Those other actors also need to be willing and able to work with them purposefully and flexibly to contribute to building positive collective efficacy beliefs about improving educational equality at the school (Lipponen and Kumpulainen, 2011; Van der Heijden et al., 2015; Bartell et al., 2019). Teachers in safe training settings can practice exchanging ideas, engage with a range of viewpoints, and work collaboratively and co-construct knowledge, using dialogue as inquiry to become more agentive in their practice (Wallen and Tormey, 2019). However, depending on the traditions, habits, and power relationships between actors, teachers who want to use their agency for social justice will experience more or fewer opportunities or barriers (Kelchtermans and Ballet, 2002). Teachers, irrespective of formal leadership roles, play a pivotal role in initiating change processes and require support from the school principal (King and Stevenson, 2017).

Concerning this domain, we defined two main manifestations (see Table 1). First, teachers acting as change agents for social justice take the initiative in the change process and collaborate purposefully (van der Heijden et al., 2015) toward more educational equality in their classroom and at the school level. The professional development program would then involve (see Table 2):

• Providing assignments and tools (i.e., strategies or tactics) participants can apply at their schools to discuss or improve social educational equality (Feature 4).

• Experimenting with these tools, working with the other participants in training settings, or working with colleagues in professional settings (Feature 5).

2.3.4 Reflexivity

Reflexivity refers to teachers’ capacity to articulate their practical knowledge (i.e., tacit knowledge) and use it to justify their practices. Reflexivity also refers to the capacity to abandon routines (Thompson and Pascal, 2012). Agency for social justice requires teachers to step back and critically reflect on their assumptions and practices to explore alternatives. Teachers can use this reflexivity to transform their schools to provide more equitable education (Pantić, 2015).

Concerning this domain, two main manifestations were defined (see Table 1). First, teachers acting as change agents for social justice should reflect systematically (Van der Heijden et al., 2015) on educational equality at the classroom and school levels. Second, they should explore alternatives to develop themselves professionally so they can improve or change the teaching practice at their school to deliver more equitable education. The professional development program would then involve (see Table 2):

• Active learning activities (e.g., discussions about the content of the lecture or activities) to analyze one’s own behavior or school policy to promote educational equality (Feature 6).

• An assignment asking teachers to explore alternatives for the teaching practice at the classroom or school level to promote educational equality (Feature 7).

2.4 Research question

The purpose of the professional development program was to contribute to agency for social justice and educational equality among experienced primary school teachers. This leads to the central question: Did the professional development program empower the participating teachers in their role as change agents for social justice? To answer this question, we map the participants’ learning experiences using the main manifestations of agency for social justice (as summarized in Table 1). In addition, we examine which features of the professional development program (see Table 2) the participants believed contributed to these learning experiences. This study provides insight into the necessary ingredients for a professional development program to promote change agency for social justice among experienced teachers.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Participants

The study was conducted in a two-year program at a university of applied sciences in the Netherlands that leads to a master’s degree in education. All participants held a bachelor’s degree that qualified them to teach in primary education. Primary schools in the Netherlands serve students from ages 4 (grade 1) to 12 (grade 8). In total, 14 teachers participated in this study: nine women and five men. They ranged in age from 28 to 52 years and had between 4 and 19 years of teaching experience. The participating teachers taught children in various grades at different schools in the Netherlands.

3.2 General picture of participants’ beliefs on educational (in)equality prior to the professional development program

Participants were asked four open-ended questions to gain insight into their beliefs and vision on educational (in)equality before the professional development program. The questions were: (1) To what extent do you see inequality between students from different family backgrounds in your class? (2) What do you see as the main reasons for educational inequality? (3) Do you see a task for yourself to combat inequality? If so, what is it? (4) What could be done at the school level to address the problem of educational inequality? The participants were given ample time to answer these questions and most took about half an hour to do so. Participants then emailed the answers to the teacher of the professional development program.

Before the professional development program, the participants mentioned that they observed inequality in educational opportunities between students from different social backgrounds. The participants believed this inequality arose from differences related to students’ social contexts, including their home language, the amount of home support, the financial situation (problematic) family situations, migration background, parents’ education, parents’ ambitions, the status of the parents’ profession, and the neighborhood where the students live. However, the participants rarely mentioned education-related factors (e.g., the teacher’s actions, the school, or the education system). For example, Teacher A: “In my opinion, the main cause is that not all parents have the capacity to guide their child. In addition, not all parents have the financial resources to take their children to a museum, for example.” Participants considered combating educational inequality to be one of their professional tasks. Their examples about how they did this mainly related to their teaching practice in the classroom. Teacher B:

The teacher’s task is to provide equal opportunities for every child. This is, of course, easy to say, but it is also really my goal. I try to honestly weigh what is needed for each child and to realize what lies within my scope.

3.3 The professional development program

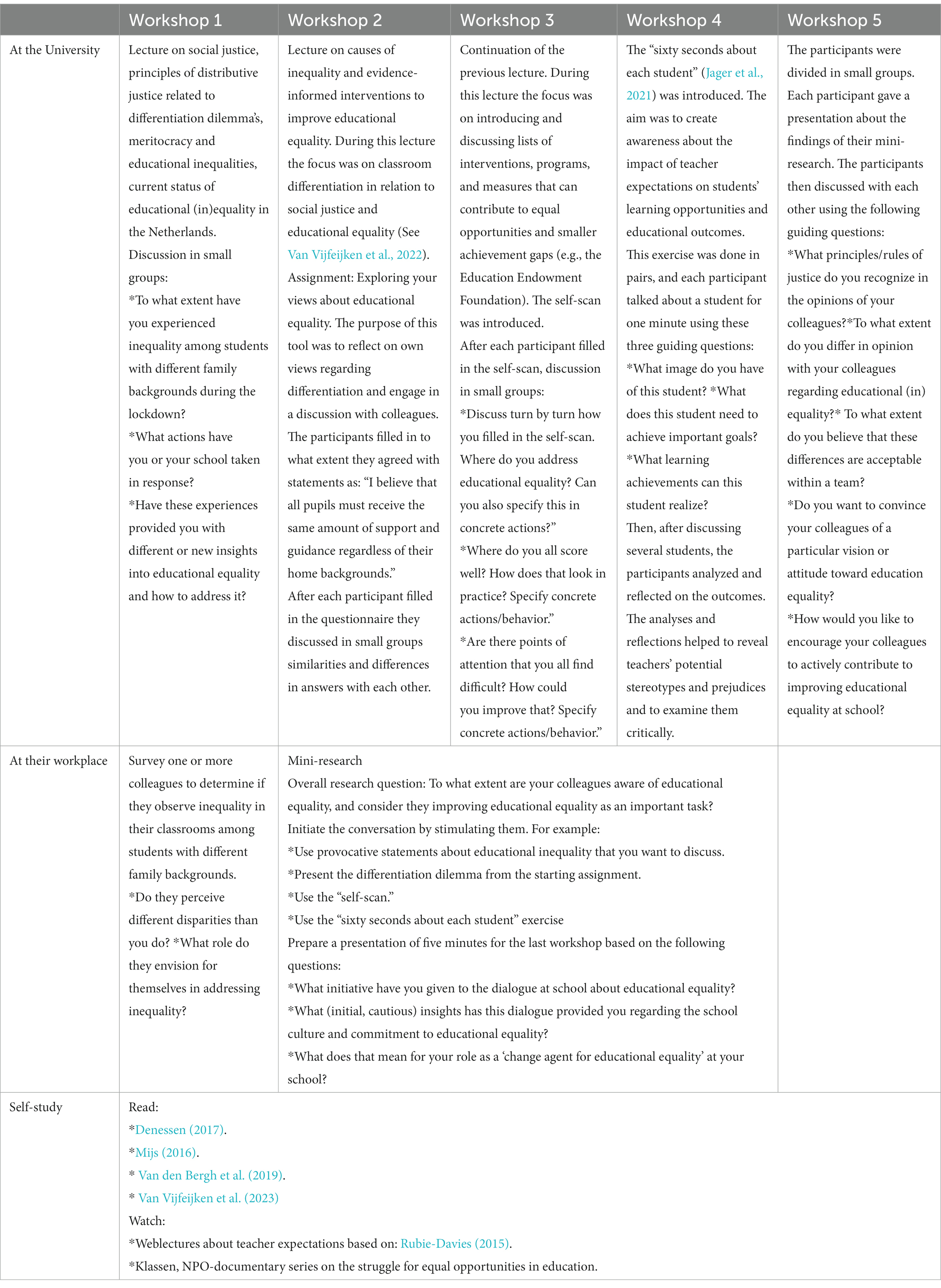

The professional development program was designed based on the “theory of change” as earlier described (see Table 2). Five workshops were designed for the professional development program, each lasting one and a half hours. The workshops were scheduled over four months with approximately three weeks intervals to provide sufficient time to practice, reflect, and self-study (Desimone, 2009; Van Veen et al., 2012). The participants were in their second training year of the master’s program. They attended classes at the university one day every two weeks and the other workdays they worked as primary school teachers. This gave them the ability to apply what they had learned in practice or carry out specific assignments. The workshops were part of a broader full-day program at the master’s program at the university. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the last two workshops were given online. The text below broadly explains the content of the workshops. References are made to the features of Table 2. The workshops are elaborated on in more detail in Table 3. The main assignments applied during the workshops have been translated into English and are openly accessible on the university’s website.1

The first workshop contained a lecture on social justice, principles of distributive justice and related (differentiation) dilemmas (Van Vijfeijken et al., 2021, 2023), meritocracy, and educational (in)equalities (Feature 1). Then, the participants were given information about educational equality in Dutch education based on reports from the Education Inspectorate. After the lecture, the participants broke into small groups to discuss and share experiences and insights regarding the lecture’s content (Feature 2).

At the end of each workshop, participants were challenged to start a dialogue with colleagues (workplace activities) (Feature 2), and to do self-study activities as watching web lectures about teacher expectations (Rubie-Davies, 2015) and to study articles about inequalities (Features 1 and 3).

The second and third workshops focused on transferring knowledge about causes of inequality and evidence-based and evidence-informed interventions to improve educational equality (Feature 3). In addition to these lectures, there was room for individual reflection and group discussion in response to the provided content (Features 2 and 6). For instance, during the third workshop, a self-scan was introduced (Feature 4). The self-scan involved seven aspects of teaching practice (differentiation and learning goals, high expectations, recognition and appreciation of differences, collaboration with parents, compensation for educational disadvantage, fair decision-making, and cooperative learning). This scan contained about seven practices per aspect that could improve educational equality. For example, “I organize no fixed homogeneous ability groups.” was a practice linked to differentiation and learning goals. In the self-scan, the teachers could indicate per practice to what extent that practice reflected their teaching practice. Participants completed the self-scan during the workshop and shared and discussed their plans to improve equal opportunities (Feature 7).

The fourth workshop focused on providing and experimenting with tools and strategies to make teachers aware of the effects of (un)conscious teacher expectations on student educational outcomes (Features 4 and 5). For instance, the “sixty seconds about each student” exercise (Jager et al., 2021) was introduced here. It aims to create awareness about the impact of teacher expectations on students’ learning opportunities and educational outcomes. This exercise was done in pairs, and each participant talked about a student for one minute using these three guiding questions: What image do you have of this student? What does this student need to achieve important goals? What learning achievements can this student realize? Then, after discussing several students, the participants analyzed and reflected on the outcomes. The analyses and reflections helped to reveal teachers’ potential stereotypes and prejudices and to examine them critically.

Finally, in the last workshop, each participant gave a presentation about the new insights they had gained and how they saw their role as change agents for social justice (Features 2 and 7). The professional development program was designed by the authors of this article and conducted by the first author.

3.4 Data collection

Kirkpatrick’s model of program evaluation (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick, 2006) was used to evaluate the professional development program. This is a widely applied evaluation model adapted to education (Praslova, 2010). This model was chosen for its simplicity and our focus on unraveling the features of the program (see Table 2) that the participants believed contributed to their individual learning experiences. Although we acknowledge that more recent conceptualizations of professional learning reveal a more reciprocal interaction between the program, the context of the participants and the participating teachers, this model was considered to fit our purposes, because the program was designed as a linear training (King et al., 2023). Kirkpatrick’s model has four levels: reaction, learning, behavior, and results. Given the scope of this study, the focus was on the reaction, learning and behavior levels. The reaction level refers to how much the participants enjoyed the training and how much they believe they have learned. The learning level refers to evaluating the educational outcomes. The behavior level, also called the transfer level, identifies the effect of training on work performance. In this study, we examined participants’ self-reported behavior. Three methods were used to collect data: individual reflection, a focus group interview, and an open questionnaire.

3.4.1 Individual reflection and focus group interviews

The individual reflection and focus group interviews were conducted immediately after the final workshop of the professional development program. The primary purpose was to obtain insights into participants’ satisfaction with the program and the extent of knowledge acquisition (reaction level), the participants’ perceived (empowered) agency for social justice (learning and behavior level) and which elements of the professional development program had contributed to this. Before the focus group interviews, participants were given 30 min to individually answer open-ended questions about the professional development program (see Appendix A). Then, the participants were randomly divided into three focus groups.

The focus group interviews were conducted online by three researchers (two of whom were not further involved in this study). The first author of this article instructed them how to conduct these interviews. The participants could explain their answers on the individual reflection form during the focus group interviews. In-depth questions were asked to gain more insight into their growth toward becoming a change agent for social justice (see Appendix A). A sample question was: “What steps have you taken or do you want to take to improve equal opportunities in your classroom or at the school level?” Participants also were asked in-depth questions about the activities of the professional development program that contributed to their growth. A sample question was: “What activities contributed most to making you feel committed to improving equal opportunity?” After the focus group interviews, participants submitted their completed reflection forms to the teacher of the professional development program.

3.4.2 Open-ended questionnaire

The open-ended questionnaire aimed to examine to what extent the professional development program had empowered participating teachers to act as change agents for social justice (learning and behavior levels). The participants were asked to answer the same open-ended questions as before they began the professional development program (see Section 3.1.2) plus two additional questions: “To what extent have you changed your mind about educational inequality?” and “To what extent did you improve your actions in your classroom and at the school level to improve educational equality, and can you provide examples?” Because Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick (2006) emphasizes that it takes time for behavior to be reflected in the participants’ actions at work (behavior level), the participants were asked to answer these questions three to six months after completing the professional development program. During this period, the participants had to deal with pandemic-related lockdowns for a few short periods, meaning they had to teach online.

3.5 Data analysis

Thematic analysis (Joanna et al., 2015) was used to code the data from the three measures (individual reflection, focus group interviews, and open-ended questionnaire) to answer the main research question (Does the professional development program empower the participating teachers in their role as change agents for social justice?). The thematic analysis enabled flexibility in coding (Braun and Clarke, 2006) by combining deductive and inductive approaches. The first step was to transcribe the focus group interviews fully. The second step was to become familiar with the data by reading through the self-evaluation data, focus group interviews, and the open questionnaire. The third step was to carry out the deductive coding of the data. The seven manifestations of agency for social justice (see Table 1) were used as coding themes. The focus was on manifestations of social justice agency that were strengthened by the professional development program, so only those manifestations for which the participants reported a change or improvement in their behavior were coded. The fourth step was inductive coding, which helped us uncover unexpected data (Punch, 2013). Developing a coding system involves searching the data for patterns and topics (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Sub-codes or sub-themes were formulated in some codes (manifestations of the agency for social justice). An example of two sub-themes was the “take initiatives” code, for which it was discovered that a distinction could be made between “planned initiatives” and “implemented initiatives.”

To ascertain the reliability of the coding, the first two authors independently coded the collected data. First, they analyzed the collected data from five participants. Then, they critically examined each other’s coding to ensure the thematic structure could be justified. Through an iterative process of further modification and review, they agreed on the sub-themes that could be applied. This coding scheme allowed the data to be thematically organized and classified. It also led to a narrative report on the strengthening of the participants’ agency for social justice due to the professional development program (see Section 4.1). Since participants were asked which activities had contributed to strengthening agency during the individual reflections and the focus group interviews, this could be added to the narrative report. The authors’ analytical comments on this report are discussed in the results and discussion section.

4 Results

The goal of the professional development program was to contribute to increasing agency for social justice and educational equality among experienced primary school teachers. In the following sections, it will be explained per domain which manifestations of agency for social justice were strengthened and which elements from the professional development program contributed to this. Each quotation includes a notation in parentheses next to the participant that indicates where the statement was made (1 = individual reflection, 2 = focus group interview, 3 = open-ended questionnaire).

4.1 A sense of purpose

4.1.1 Being committed—shift from classroom level commitment to classroom and school level commitment

The participants expanded their professional task from ensuring educational equality in their classroom to promoting educational equality at the school level. After the professional development program, they indicated that they feel responsible for initiating activities that could improve educational equality at the school level. Teacher C (2): “Because no one automatically starts talking about it, we have to do that.” The participants wanted to transfer the awareness and knowledge they had gained to their colleagues. Teacher B (3):

It has become an important theme for me as I have gained more knowledge about it and have come to realize that the choices we make as teachers can have far-reaching consequences. This means I remain aware and try to put educational equality on the team’s agenda.

The evaluations revealed that no specific content or activity contributed to extending that commitment to the school level. Instead, the individual reflections listed almost all of the activities as important in affecting their commitment. As Teacher C stated (1): “Reading literature, the dialogue during the lectures, watching video fragments and the web lectures: it really is the total that had an impact.” As Teacher C stated (1): “Reading literature, the dialogue during the lectures, watching video fragments and the web lectures: it really is the total that had an impact.”

4.1.2 Examining beliefs and vision—ongoing search process

The professional development program made the participants think about their beliefs and visions of social justice and educational equality. The evaluations suggest that the process of searching for personal beliefs or opinions was still ongoing after the professional development program. Teacher D (2): “I still go back and forth, and that’s because of all the opinions you read. And that helps you in that, but I’m not yet that far that I can say: that’s how I stand with it.” The search for self-concepts expressed by the teachers focused on values related to social justice principles. The participants needed to become more familiar with the term “social justice.” Specifically, they were unfamiliar with including distributional principles or values from social justice theory in their vision of education. Teacher E (2): “I have gained insight into social justice and educational equality, but I could perhaps delve more into that.” The participants asserted that it was rare to discuss social justice and educational equality and develop a joint vision at their schools. After the professional development program, the participants indicated they wanted to have a dialogue at their school to reach a shared vision. Teacher C (2):

And what I got out of these lectures is, yes, what principle are we reasoning from? What is our vision? And I’m thinking about whether we want to strive for equal input or equal output…well, you name all those equality rules. So those are added values I want to discuss with my colleagues.

The evaluations showed the participants felt that the lectures on social justice, the differentiation dilemmas (Van Vijfeijken et al., 2021, 2023), and meritocracy were the most important triggers for examining one’s own vision and opinions. However, these contents were experienced as complex. Teacher F (2): “Social justice is very interesting, but I notice that it takes me a little longer to understand the principles at once, so to speak.” What was still missing from the professional development program was an assignment in which the participants could actively transform these theories into educational practice.

4.2 Competence

4.2.1 Being experts—have more knowledge than colleagues

Although the participants were experienced teachers, they felt the professional development program gave them new knowledge and ideas they could use to improve educational equality. After the professional development program, they felt more expert than their colleagues. This strengthened their feeling that they are the ones who can act as a driving force to improve educational equality at the school level. Teacher A (3): “They still know little about this on the team. It is my task to give them more insight into educational inequalities.” Their increased expertise led the participants to have confidence in their ability to enter into a dialogue with colleagues and the school principal and to convey the importance of paying attention to educational equality.

The evaluations showed that the participants found the content provided with (evidence-based and evidence-informed) interventions for improving educational equality during the lectures, web lectures, and self-study material to be essential to increasing their expertise. They also mentioned that conversations with fellow participants or colleagues about the content had increased their expertise. The time reserved in the lectures for such discussions and the assignments for the workplace were necessary to develop the participants’ expertise. This also shows that the participants were critical and wanted to avoid blindly adopting new insights into their practice; instead, they wanted to discuss them.

4.3 Autonomy

4.3.1 Taking the initiatives—planned initiatives and implemented activities

The participants identified initiatives they still intend to implement in favor of educational equality. Teacher G (1): “I am going to make educational equality a subject of discussion by sharing knowledge and stimulating the discussion about how this will be given a place in our education.” Participants also identified initiatives they had carried out during and after the professional development program. Some shared knowledge about educational equality and/or organized a study afternoon to inspire their colleagues. Others had taken the initiative to reexamine previous practices in light of educational equality (e.g., joint agreements about the use of grouping forms in cognitive subjects or the policy the team used when advising students about the transition from primary to secondary education). Teacher E described starting research into how flexible grouping of students could contribute to educational equality at their school (3): “I have started talking with my colleagues about how we can create flexible instruction groups to increase equality of opportunity. Ultimately, we want to create new agreements about grouping students and put these agreements on a quality map.” Some participants noted that they had informally taken the initiative to make educational equality a subject of discussion in their school team. They did this by reacting directly to situations where there was a risk of inequality or social injustice. Teacher H (2):

I now notice more often that colleagues use children’s home situations as an excuse to lower expectations about these students. I react very strongly to that now. Now, I’m saying, “Guys, don’t do that. Don’t let this student down.”

The evaluations showed that the content, the self-scan, and the “sixty seconds about each student” exercise they experimented with during the workshops enhanced the participants’ ability to act. The participants mentioned that completing the self-scan had increased their awareness about choices that could lead to equal or less equal opportunities for all students. Teacher E (1): “Actually ‘measure’ what you are doing or not doing with the self-scan.” In addition, the self-scan helped the participants determine, together with their colleagues, which adjustments they could make in their teaching to improve educational equality. They appreciated the self-scan because of the concrete aspects it described based on knowledge about improving educational equality. Teacher I (2):

That scan was full of small concrete, practical matters you can directly trace back to how you are doing in class. Those kinds of matters are easy to discuss in a team and with colleagues because they recognize them very quickly. We can do a lot with small adjustments in our teaching practice in the classroom and at the school level.

The evaluations showed that the participants appreciated the “sixty seconds about each student” exercise because they consider it a powerful reflection tool. Teacher I: “That was a great step-by-step plan. And then I thought, this is also nice to do with colleagues. You then really look at your actions concerning educational equality. And the reflection moment that it contains is powerful.” The participants found the dialogues with fellow participants that were created by both tools particularly relevant. Several participants indicated that they would like to use these tools with their colleagues.

4.3.2 Collaborating—differences in perceived professional space

Most of the initiatives planned and implemented at participants’ schools focused on collaboration. Teacher J (3): “I am not going to make a difference on my own, but together with my team, I will!” Participants who were able to exert agency received positive reactions from their team. For example, Teacher E sent colleagues an article with reflection questions that had also been discussed in the workshops. The colleagues’ reactions were positive (2): “Yes, they found the questions difficult, but also super interesting, and I think I have very passionate colleagues, so they absorb it like a sponge.” Subsequently, Teacher E felt empowered to initiate more actions to improve educational equality.

The evaluation showed that the participants used the various input (e.g., articles, tools) of the professional development program to collaborate with their colleagues. However, participants differed in the extent to which they could implement initiatives or (be able to) take the space to exert influence. For example, Teacher C had a different experience. Their colleagues did not read the literature Teacher C shared and, in their opinion, that was characteristic of the culture at the school (3): “Yes, my colleagues ignored the information, even after I sent a reminder.” Teacher C also experienced no support from the school principal (3): “My school principal said: ‘Do you know how many articles I get? I am so afraid that I overload you all with information.” These experiences reduced Teacher C’s perceived space to manifest agency. In addition, Teacher C felt insecure about how to bring educational inequality to the attention of the team without giving them the impression they were not doing their job well (3): “How do you handle that without making colleagues feel like they have not done a good job so far, you know, things like that?” The professional development program provided little guidance for participants who perceived little space to address educational equality.

4.4 Reflexivity

4.4.1 Reflecting (systematically)—more reflection on educational equality at the school

The participants indicated that the professional development program had made them reflect on equal opportunities in educational practice. This made them more aware of educational inequalities. For example, participants stated that they had underestimated educational inequality as a problem. Teacher C (3): “I was a bit more naïve. I thought the problem was not too bad, but I have become more aware of the magnitude of the problem.” Teacher J (1): “I now see that it can also play a role in my daily teaching practice.” Before the professional development program, the participants mainly named causes of inequality from the viewpoint of the student and (the background of the) parents. In the evaluations, the participants reflected more on possible causes of inequality from the perspective of the social context, the school system, the school, and their own (unconscious) actions. Teacher I (2):

Yes, I am more aware that I must consider whether my actions lead to equal opportunities. And there are also topics I would really like to discuss with the team. For instance, we assign homework, and I wonder if we should because children come from different families that provide them with different amounts of support. Some parents will do the homework for the student, while other students have to do it all by themselves. So, I find it interesting to discuss this with my colleagues in terms of educational equality.

Participants regularly mentioned that they wanted to include the educational equality perspective in school development or innovations. Teacher J (1): “Before this program, I had not studied it in depth and I had never spoken about it at school. Now it is in my head as a ‘value,’ and I will always consider this perspective in school development.” Participants also became more critical of policies at their schools. Teacher L (2): “Now you ask your colleagues critical questions. Are we doing it right in light of equal opportunity?” Some participants became more critical of the Dutch education system. Teacher D (2): “Because our system is built upon those class differences. If we continue to approach pre-university education students as better than pre-vocational secondary education students, everything will stay the same.”

The evaluations showed that dialogue between the participants and colleagues at their schools had been essential to strengthening reflexivity. Their reflexivity helped them translate the information provided in the professional development program into their educational practice, and it taught them to look at educational equality from multiple perspectives. Teacher C (1):

I always found the discussion interesting. I was asking questions and talking with the teacher and fellow students. I feel like some things are more nuanced than some literature presents, so I needed to do more than just read the literature.

4.4.2 Exploring alternatives—exploration in collaboration with colleagues

The participants indicated that the professional development program had made them reflect on improving their professionalism. This could be deduced from statements such as Teacher F’s (2): “What can I still do to improve myself?” Participants also stated that they wanted to develop initiatives with colleagues to explore suitable interventions. Teacher B (3): “I’m exploring how to get started with this in practice.” From some examples, it became clear that participants broke through certain daily routines after the professional development program (e.g., no longer using homogeneous ability groups).

The evaluations showed that no specific content or activity contributed to exploring alternative courses of action at the classroom or school level. In other words, it was more the total program that had contributed to that.

5 Discussion

5.1 Empowered sense of agency

This study evaluated a professional development program designed for experienced primary school teachers and examined the elements contributing to teachers’ agency for social justice and educational equality. We aimed to fill the knowledge gap regarding what teachers empower to adopt a role as a change agent for social justice and education equality. Therefore, we designed a “theory of change” with seven manifestations of agency for social justice based on earlier studies (e.g., Pantić, 2015; Van der Heijden et al., 2015): (1) being committed, (2) examining beliefs and vision, (3) being experts, (4) taking the initiative, (5) collaborating, (6) reflecting (systematically) and (7) exploring alternatives (see Table 1). In addition, core features of effective professionalization interventions (e.g., Desimone, 2009; Van Veen et al., 2012) were incorporated into the design of the professional development program which had led to seven features (see Table 2) of the professional development program (e.g., lecture about evidence-informed practical interventions to promote educational equality and assignments to discuss and examine own behavior or the current school policy to promote educational equality).” The central question: Did the professional development program empower the participating teachers in their role as change agents for social justice?

An empowered sense of agency for social justice was manifested. It seemed that the participants expanded their professional task from ensuring educational equality in their classroom to promoting educational equality at the school level (Domain, A sense of purpose). Such a task concept that is not only aimed at bringing about a change in personal behavior but also has an impact at the school level fits the characteristics of a change agent (Villegas and Lucas, 2002; Van der Heijden et al., 2015). By broadening the participants’ commitment at the school level, the professional development program strengthened the participants’ agency for social justice. Although previous studies have indicated that teachers and school teams often lack familiarity with linking social justice values to their personal or collective perspectives on education (Biesta et al., 2015; Pantić, 2017; Van Vijfeijken et al., 2023), the professional development program proved effective in fostering a desire among the participants to connect social justice values to their beliefs and the school’s vision. This can be seen as a first step in the process of taking a clear or critical stance in the discourse to promote social justice and educational equality. The ability to act as change agents for social justice requires strong commitment and persistence (Villegas and Lucas, 2002; Cochran-Smith et al., 2016; Bartell et al., 2019).

After the professional development program, the participants felt more expert than their colleagues (Domain, competence). Comprehensive knowledge and skills are crucial to receiving colleagues’ support for initiatives that lead to change at the school level (Van der Heijden et al., 2015). The participants were critical and wanted to avoid blindly adopting new insights from the professional development program into their practice; instead, they wanted to discuss them. Adopting a critical attitude is one characteristic of teachers who act as change agents (Sannino, 2010; Van der Heijden et al., 2015).

The participants identified initiatives they still intend to implement in favor of educational equality and initiatives they had carried out during and after the professional development program (Domain, Autonomy). The professional development program strengthened the participants’ capacity for action, an essential aspect of change agency (Van der Heijden et al., 2015). The results might also suggest that the participants dared to experiment systematically to look for alternatives that distribute educational opportunities or educational outcomes more fairly. The courage to experiment fits the characteristics of a change agent (Van der Heijden et al., 2015). Most of the initiatives planned and implemented at participants’ schools focused on collaboration. However, they experienced different degrees of power to act as change agents within the context of their school, given the levels of autonomy and interdependence with the other actors (Pantić, 2015). To be able to act as change agents, teachers need other actors to be willing and able to collaborate purposefully to contribute to positive collective “efficacy beliefs” regarding improving educational equality (Bartell et al., 2019). Especially the school principal is crucial in this regard, as teachers require support from the school principal to initiate processes of change (King and Stevenson, 2017). Not all participants, however, were found to receive this support.

The professional development program strengthened the teachers’ reflective attitude toward educational (in)equality (Domain, Reflexivity). Reflexivity is needed to justify practices related to equitable education (Pantić, 2015), and developing agency for social justice requires a critical attitude toward educational practice and inequality in the education system and society (Cochran-Smith et al., 2016). Moreover, the participants broke through certain daily routines crucial for change agents to dare (Thompson and Pascal, 2012), especially those routines where educational equality may be at stake.

5.2 Lessons learned

Built on the results of this evaluation study, we suggest seven lessons learned about an effective professional development program for in-service teachers aimed at promoting agency for social justice.

1. Provide a wide range of content and learning activities. We posit that, in a professionalization program where a commitment to promoting social justice is crucial, it is not merely a singular activity or content that contributes, but rather the entirety of the program.

2. Allow sufficient time and support in the program for teachers to become familiar with social justice and educational equality terms and theories. Social justice principles can be valuable in exploring one’s own views on education and developing shared views about equal educational opportunities at the school level. Since most teachers are unfamiliar with social justice theory, it seems important to devote sufficient time to this and to offer support for translating social justice principles to practice.

3. Teach evidence-based and evidence-informed knowledge about practical educational equality interventions and allocate time for in-depth discussions on the application of these interventions. In other words, the program should go beyond the mere transmission of information and reserve time for participants to engage in explicit discussions on the practical relevance and applicability of these interventions. The evaluation results indicated a preference among participants to refrain from blindly adopting new insights into their practice.

4. Provide valuable tools and strategies teachers can use to start a dialogue about educational equality at the school. The participants expressed that the discussions during the workshops, which were based on the content of the professional development program, contributed to transferring the acquired knowledge to practice. The “self-scan” and the “sixty seconds about each student” exercise were particularly appreciated.

5. Let teachers experiment with conducting a dialogue about social justice and educational equality in the safe context of training sessions. Teachers benefit from experimenting and engaging in dialogue with colleagues who work at other schools in a safe learning environment, such as the professional development program.

6. Organize participants’ exchange of experiences and mutual support, especially for those teachers who experience less willingness and capacity from other actors at their school to promote educational equality.

7. Consult the school management in advance to determine what extra support (individual) teachers and school teams may need to take steps toward more educational equality. During this consultation, the significance of garnering support from the school principal must be emphasized for teachers to be able to initiate change processes.

5.3 Follow-up research questions

The professional development program empowered teachers’ agency for social justice and educational equality. We addressed two opportunities for improvement and further research. First, teachers and school teams seemed to be unfamiliar with discussing ethical dilemmas and connecting social justice values to personal or collective views on education (Biesta et al., 2015; Pantić, 2017; Van Vijfeijken et al., 2023). The evaluated professional development program showed that lectures about social justice, the differentiation dilemmas and meritocracy are crucial triggers for examining one’s own vision and opinions. However, these contents were experienced as complex. The professional development program lacked an assignment in which the participants could actively transform these theories into educational practice. A follow-up question to this study is: What are relevant and suitable methods for increasing teachers’ knowledge of social justice in a way that allows them to apply it in making responsible educational decisions?

Second, to be able to act as change agents, teachers need other actors to be willing and able to collaborate purposefully to contribute to positive collective “efficacy beliefs” regarding improving educational equality (Bartell et al., 2019). An essential factor in this is support and trust from the school’s management. Furthermore, teachers’ perceived and exploited space to initiate collective initiatives is influenced by personal and contextual factors (Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., 2017). From a personal point of view, the uncertainty of individual teachers can hinder the manifestation and development of agency (Kauppinen et al., 2020). From a contextual point of view, a school’s culture can negatively affect the teacher’s ability to manifest agency (e.g., because of a lack of trust in the school’s management). These hindrances were not identified at the onset of the professional development program. The findings of this study underline the importance of identifying the learning needs of individual teachers with regard to their school’s context or culture at the start of the program. An interesting question for future research would be: How can school communities be involved in a professionalization program to increase individual teachers’ agency for social justice? Another interesting question would be how the professional development program could provide more attention to students’ various school contexts in order to learn how these might affect their agency and discuss possibilities to develop agency in ways that are better attuned to their personal work contexts.

5.4 Limitations

This study had some limitations. The first author knew the participants because she was the teacher for the professional development program, so some comments in the written evaluations may have been less critical than if the assessments had been anonymous. However, the students were used to conducting formative evaluations from a critical distance at part of their master’s program. In addition, participants received no credits for attending the workshops and completing the assignments. To ascertain the reliability of the coding, the data were independently coded by the first and the second author. The latter did not know the participants. Furthermore, the measurements of this evaluation study mostly came from self-reports (Copur-Gencturk and Thacker, 2021). We tried to minimize the effects of this limitation by examining the data from different measures (i.e., individual reflection, focus group interviews, and open-ended questions) and encouraging openness and honesty during the evaluation process.

5.5 Implications for the initial teacher education

Although the professional development program evaluated in this study involved experienced teachers, the findings are also relevant for initial teacher training and (other) master’s programs in education. The experienced teachers seemed to be unfamiliar with analyzing and specifying values. And before beginning the professional development program the participating teachers lacked comprehensive knowledge about concepts like meritocracy, educational equality, and social justice. Therefore, we recommend that more attention be paid to social (in)justice and educational (in)equality in initial teacher education to encourage teachers to explore their own beliefs and values. Comprehensive knowledge about social justice and educational equality will help prepare teachers to engage in the public debate about educational equality. Although the entire professional development program cannot be adopted as a blueprint in initial teacher training, parts of it probably can. For example, in teacher education, prospective teachers can learn about the meritocratic education system and develop a critical attitude toward it through discussion with peers or with colleagues during the internship. Furthermore, they can attend lectures on evidence-based and evidence-informed interventions in the classroom that contribute to improving equal opportunities. Paying more attention to educational inequality in teacher education might inspire new teachers to want to learn how to act as change agents for social justice and educational equality.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MV, TS-M, LB, RS, and ED contributed to the conception and design of the study. MV and TS-M contributed to qualitative analysis and analyzed and coded qualitative data, which was discussed in iteration with the whole team until the results became clear. MV prepared the manuscript. TS-M, LB, RS, and ED were involved in publication planning, providing advice on directions for the research and manuscript, reading drafts, and giving suggestions for changes and feedback on the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participating teachers in the professional development program for their contributions to the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1244113/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: lessons from international experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 6, 7–16. doi: 10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587

Autin, F., Batruch, A., and Butera, F. (2015). Social justice in education: how the function of selection in educational institutions predicts support for (non)egalitarian assessment practices. Front. Psychol. 6:707. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00707

Bartell, T., Cho, C., Drake, C., Petchauer, E., and Richmond, G. (2019). Teacher agency and resilience in the age of neoliberalism. J. Teach. Educ. 70, 302–305. doi: 10.1177/0022487119865216

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., and Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 21, 624–640. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

Bradbury, B., Corak, M., and Waldfogel, J., nd Washbrook, E. (2011). Inequality during the early years: child outcomes and readiness to learn in Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, and United States. Bonn, IZA – Institute of Labor Economics

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brighouse, H., Ladd, H. F., Loeb, S., and Swift, A. (2018). Educational goods: values, evidence, and decision-making. Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press.

Cochran-Smith, M., Craig, C. J., Orland-Barak, L., Cole, C., and Hill-Jackson, V. (2022). Agents, agency, and teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 73, 445–448. doi: 10.1177/00224871221123724

Cochran-Smith, M., Ell, F., Grudnoff, L., Haigh, M., Hill, M., and Ludlow, L. (2016). Initial teacher education: what does it take to put equity at the center? Teach. Teach. Educ. 57, 67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.006

Copur-Gencturk, Y., and Thacker, I. (2021). A comparison of perceived and observed learning from professional development: relationships among self-reports, direct assessments, and teacher characteristics. J. Teach. Educ. 72, 138–151. doi: 10.1177/0022487119899101

Cropanzano, R., and Molina, C. (2017). “Organizational justice” in International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. ed. J. D. Wright. 2nd ed (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 379–384.

Denessen, E. (2017). Ongelijke kansen in het onderwijs: verklaringen en voorstellen voor beleid [Inequality in education: explanations and policy proposals]. Jubileum uitgave 1992–2017. In K. Hoogeveen, J. IJsbrand, and F. Studulski, (Red.), Kansen bieden in plaats van uitsluiten. Jubileum Uitgave 1992–2017 (pp. 19–39). Utrecht: Sardes.

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educ. Res. 38, 181–199. doi: 10.3102/0013189X08331140

Deutsch, M. (1975). Equity, equality, and need: what determines which value will be used as the basis of distributive justice? J. Soc. Issues 31, 137–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1975.tb01000.x

Espinoza, O. (2007). Solving the equity-equality conceptual dilemma: a new model for analysis of the educational process. Educ. Res. 49, 343–363. doi: 10.1080/00131880701717198

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., and Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educ. Res. Rev. 10, 45–65. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Florian, L., and Spratt, J. (2013). Enacting inclusion: a framework for interrogating inclusive practice. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 28, 119–135. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2013.778111

Francis, B., Mills, M., and Lupton, R. (2017). Towards social justice in education: contradictions and dilemmas. J. Educ. Policy 32, 414–431. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2016.1276218

Francis, B., Taylor, B., and Tereshchenko, A. (2019). Reassessing ‘ABILITY’GROUPING: improving practice for equity and attainment. New York: Routledge

Fullan, M. (2016). The new meaning of educational change (5th ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge, Polity Press; Blackwell.

Grant, C. A., and Agosto, V. (2008). “Teacher capacity and social justice in teacher education”, Educational Leadership and Policy Studies Faculty Publications 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=els_facpu

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York: Routledge.

Jager, L., Denessen, E., Cillessen, A. H., and Meijer, P. C. (2021). Sixty seconds about each student–studying qualitative and quantitative differences in teachers’ knowledge and perceptions of their students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 24, 1–35. doi: 10.1007/s11218-020-09603-w

Joanna, B., Serena, M., Emma, T., and Nigel, K. (2015). The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 12, 202–222. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

Kauppinen, M., Kainulainen, S., Hökkä, P., and Vähäsantanen, K. (2020). Professional agency and its features in supporting teachers’ learning during an in-service education programme. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 384–404. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1746264

Kelchtermans, G., and Ballet, K. (2002). Micropolitical literacy: reconstructing a neglected dimension in teacher development. Int. J. Educ. Res. 37, 755–767. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(03)00069-7

King, F., Poekert, P., and Pierre, T. (2023). A pragmatic meta-model to navigate complexity in teachers’ professional learning. Prof. Dev. Educ. 49, 958–977. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2023.2248478

King, F., and Stevenson, H. (2017). Generating change from below: what role for leadership from above? J. Educ. Adm. 55, 657–670. doi: 10.1108/JEA-07-2016-0074

Kirkpatrick, D., and Kirkpatrick, J. (2006). Evaluating training programs: the four levels. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Korthagen, F. A. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 20, 77–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2003.10.002

Lipponen, L., and Kumpulainen, K. (2011). Acting as accountable authors: creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.001

Mijs, J. J. B. (2016). The unfulfillable promise of meritocracy: three lessons and their implications for justice in education. Soc. Justice Res 29, 14–34. doi: 10.1007/s11211-014-0228-0

Miller, C. M., and Martin, B. N. (2015). Principal preparedness for leading in demographically changing schools: where is the social justice training? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 43, 129–151. doi: 10.1177/1741143213513185

Min, M., Lee, H., Hodge, C., and Croxton, N. (2021). What empowers teachers to become social justice-oriented change agents? Influential factors on teacher agency toward culturally responsive teaching. Educ. Urban Soc. 54, 560–584. doi: 10.1177/00131245211027511

OECD. (2023). Equity and inclusion in education: finding strength through diversity. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

Oolbekkink-Marchand, H. W., Hadar, L. L., Smith, K., Ulvik, M., and Helleve, I. (2017). Teachers' perceived professional space and their agency. Teach. Teach. Educ. 62, 37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.11.005

Pantić, N. (2015). A model for study of teacher agency for social justice. Teach. Teach. 21, 759–778. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044332

Pantić, N. (2017). An exploratory study of teacher agency for social justice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 66, 219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.04.008

Pantić, N., and Florian, L. (2015). Developing teachers as agents of inclusion and social justice. Educ. Inq. 6, 333–351. doi: 10.3402/edui.v6.27311

Pantić, N., Taiwo, M., and Martindale, A. (2019). Roles, practices and contexts for acting as agents of social justice–student teachers’ perspectives. Teach. Teach. 25, 220–239. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2018.1562441

Pantić, N., and Wubbels, T. (2010). Teacher competencies as a basis for teacher education–views of Serbian teachers and teacher educators. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 694–703. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.005

Praslova, L. (2010). Adaptation of Kirkpatrick’s four level model of training criteria to assessment of learning outcomes and program evaluation in higher education. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 22, 215–225. doi: 10.1007/s11092-010-9098-7

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Sage.

Rawls, J. (1999). A theory of justice (rev. ed.). Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Resh, N., and Sabbagh, C. (2016). “Justice and education” in Handbook of social justice theory and research. eds. C. Sabbagh and M. Schmitt (Berlin: Springer), 349–367.

Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2015). Becoming a high expectation teacher: raising the bar. New York: Routledge.

Sannino, A. (2010). Teachers' talk of experiencing: conflict, resistance and agency. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.021

Thompson, N., and Pascal, J. (2012). Developing critically reflective practice. Reflective Pract. 13, 311–325. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2012.657795

Toom, A., Pyhältö, K., and Rust, F. O. C. (2015). Teachers’ professional agency in contradictory times. Teach. Teach. 21, 615–623. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044334

Van den Bergh, L., Denessen, E., and Volman, M. (2019). Werk maken van gelijke kansen. Praktische inzichten uit onderzoek voor leraren basisonderwijs. [Taking action for equal opportunities: Practical insights from research for primary school teachers]. Meppel: Didactief onderzoek.

Van der Heijden, H. R. M. A., Geldens, J. J. M., Beijaard, D., and Popeijus, H. L. (2015). Characteristics of teachers as change agents. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 21, 681–699. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044328

Van Veen, K., Zwart, R., and Meirink, J. (2012). What makes teacher professional development effective? A literature review. In M. Kooy and K. Veenvan, eds., Teacher learning that matters, 23–41. New York: Routledge

Van Vijfeijken, M. (Ed) (2022). Wat is eerlijk? Werken aan kansengelijkheid in het onderwijs. [What is fair? Promoting educational equality]. PICA.

Van Vijfeijken, M., Van Schilt-Mol, T., Scholte, R. H. J., and Denessen, E. (2021). Equity, equality, and need: a qualitative study into teachers’ professional trade-offs in justifying their differentiation practice. Open J. Soc. Sci. 9, 236–257. doi: 10.4236/jss.2021.98017

Van Vijfeijken, M., Van Schilt-Mol, T., Van den Bergh, L., Scholte, R. H. J., and Denessen, E. (2023). How teachers handle differentiation dilemmas in the context of a school’s vision: a case study. Cogent Educ. 10, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2023.2165006

Villegas, A. M., and Lucas, T. (2002). Educating culturally responsive teachers: a coherent approach. New York: Suny Press.

Wallen, M., and Tormey, R. (2019). Developing teacher agency through dialogue. Teach. Teach. Educ. 82, 129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.03.014

Wang, Y., Mu, G. M., and Zhang, L. (2017). Chinese inclusive education teachers' agency within temporal-relational contexts. Teach. Teach. Educ. 61, 115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.009

Keywords: change agents, agency, social justice, educational equality, professional development

Citation: van Vijfeijken M, van Schilt-Mol T, van den Bergh L, Scholte RHJ and Denessen E (2024) An evaluation of a professional development program aimed at empowering teachers’ agency for social justice. Front. Educ. 9:1244113. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1244113

Edited by:

Luiz Sanches Neto, Federal University of Ceara, BrazilReviewed by:

Giovanna Barzano, Ministry of Education, Universities and Research, ItalyFiona King, Dublin City University, Ireland

Copyright © 2024 van Vijfeijken, van Schilt-Mol, van den Bergh, Scholte and Denessen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marijke van Vijfeijken, marijke.vanvijfeijken@han.nl

Marijke van Vijfeijken

Marijke van Vijfeijken Tamara van Schilt-Mol

Tamara van Schilt-Mol Linda van den Bergh

Linda van den Bergh Ron H. J. Scholte3

Ron H. J. Scholte3