Political Performances of Control During COVID-19: Controlling and Contesting Democracy in Germany

- Institute for European Studies, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Drawing from interpretive, namely discursive-performative approaches to both institutional and grassroots (populist) politics, this article explores political performances and counter-performances of control in Germany during the so-called first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Methodologically, the article constructs a comparative analytical framework including three cases from both within and outside of the federal institutional structure of Germany: at the institutional level, the cases comprise Angela Merkel, long-term federal Chancellor of Germany, and Michael Kretschmer, the regional Governor of the state of Saxony; at the grassroots level, the selected case is the populist protest movement “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident” (Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes, PEGIDA). Based on original empirical data generated using the toolkit of qualitative-interpretive methodology, notably online ethnography, the comparative analysis focuses on a few key counter-performances of control, among them a TV address (Merkel), a visit to an “anti-lockdown” demonstration (Kretschmer), and virtual protest events (PEGIDA). Emphasizing the performed, dynamic, and contested character of political control in Germany in spring 2020, the empirical analysis yields the following results: first, it sheds light on the different political styles of performing and contesting institutional control, including the habitus, modes, and (emotional) tones of the communication of the performers, and the scripts, stages, intended audiences as (imagined) constituencies, and modalities of transmission of their performances. Second, the discourse-theoretical perspective of the analysis reveals that political performances of control were closely linked to articulations of democracy as an empty signifier, and to claims for safeguarding democratic principles as such. Third, the article demonstrates the value of interpretive approaches to politics to generate more nuanced understandings of the relationships between the pandemic, democracy, and populism in a situation of an ultimate lack of control.

Introduction

“It is serious. Therefore, take it serious,” were the most quoted words of the German Chancellor Angela Merkel in the televised “address to the nation” of March 18, 2020. By that date, the COVID-19 pandemic had hit each of the 16 federal states of the country, Germany had registered more than 10,000 infections with the new coronavirus, and more than 30 people had died. In response, the German national and regional administration had largely “locked down” public life, closed the external borders, and appealed to the population to practice “social distancing.” In her TV address, Merkel justified the extraordinary regulations by marking the historic dimensions of the crisis caused by the pandemic: “since German Unity, no, since the Second World War, our country did not face a challenge in which it depended so much on our common solidary actions.” To commentators, Chancellor Merkel's TV address stood out due to its unexpected emotional appeal and genuine empathy (Jahn, 2020; Seminar für Allgemeine Rhetorik, 2020). Taking account of its extraordinary format and content as well as the modalities of its transmission, the speech can also be approached as a formidable attempt to “perform control” during the crisis: it was carefully staged and disseminated to construct Merkel as “being in control” of the development of the pandemic and the institutional responses to it. As an outstanding example for the “showing of a doing,” it qualifies as a political performance aiming to demonstrate Merkel's “political presence, activity, progress, and engagement” (Gluhovic et al., 2021, p. 15).

Similar to Merkel, numerous political and public actors in Germany staged and disseminated performances of control in spring 2020. Next to the federal health minister, the heads of the regional governments, namely the 16 regional Governors and mayors of the Bundesländer, were among the most visible actors. In fact, due to the federal structure of Germany, important competencies relating to the execution of health policies decided at the federal level lie with the federal states, thus creating a much-criticized state of legal uncertainty throughout the first wave of the pandemic (Behnke, 2020; Merkel, 2020). Additionally, two expert institutions, namely the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), the German federal government agency responsible for disease prevention and control, and Christian Drosten, virologist and then-director of the largest university hospital in Berlin, became chief public performers (Moser, 2020). At the same time, oppositional actors contested federal and regional institutional responses to the pandemic: both established and new protest actors, the latter mainly associated with the emerging so-called Querdenken (“lateral thinkers”) movement (Teune, 2021), staged and broadcast counter-performances in virtual and public spaces to demonstrate their rejection of the institutional claims to being in control and constituting themselves as performers of control.

In light of the struggles to perform control over and during the pandemic, this article explores how a few political actors performed control at both the institutional and grassroots levels of the federal structure of Germany during the so-called first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the article compares the performances of control by two institutional actors in executive roles within the German federal polity, namely the federal Chancellor, Angela Merkel, and the regional Governor of the state of Saxony, Michael Kretschmer, and by one counter-institutional grassroots actor, that is the Dresden-based far-right populist protest movement “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident” (Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes, PEGIDA). The time period of the study ranges from mid-March to mid-May 2020. Besides showcasing some of the political styles used to perform and contest institutional control, the comparative analysis reveals that political performances of control in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic were crucially characterized by constant appeals to the idea(l) of democracy when framing the pandemic and “lockdown.” Even though Germany figured within the European average with regard to the legal restrictions to democratic freedoms (Engler et al., 2021), the articulation of democratic principles, especially the trade-off between pandemic-related restrictions and civil rights, played a dominant role from Merkel's TV address onward and further crystallized in the context of the particularly strong anti-lockdown Querdenken mobilization in Germany. The salience of the concept and lived reality of democracy in Germany during the crisis distinguishes the German case from other European countries and renders it interesting for further analysis.

This article aims to contribute to scholarship in various ways: from a theoretical perspective, it offers a novel approach to studying political control, drawing from interpretive (Bevir and Rhodes, 2016), and specifically discourse-theoretical and performative approaches to politics (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985; Saward, 2010; Moffitt, 2016; Rai et al., 2021). In contrast to legal perspectives which understand control as static competencies prescribed to institutions in legal texts, and in line with the notion of the “representative claim” proposed by Saward (2010), the article highlights the performed, dynamic, and contested character of control in democratic contexts. Taking a constructivist stance on what it means to “be in control,” it argues that control is nothing that a political actor inherently possesses but something that needs to be constantly (re-)articulated in political performances. As the “showing of a doing,” it conceives of performances as carefully staged and purposefully disseminated discursive events that aim to articulate political meaning (Rai, 2014; Rai et al., 2021). In politics, they constitute the primary tool to articulate “being in control,” namely by demonstrating “political presence, activity, progress, and engagement (or so the actors and organizers hope) and an opening to critical appraisal and accountability of the leader or official” (Gluhovic et al., 2021, p. 15; Rai, 2014). The article thus conceptualizes performances of control during the COVID-19 pandemic as strategic discursive events that construct political meaning, namely the performer as “being in control.” Also, it proposes that the particular design and aesthetics of individual performances disclose specific political styles (Saward, 2010; Moffitt, 2016).

In addition, this study uses the notion of “counter-performance of control” to refer to the articulation of counter-hegemonic political meaning by the far-right populist movement PEGIDA, including the contestation of hegemonic meaning-making, namely institutional control during the crisis. The theoretical take thus emphasizes that performing control during a crisis is not only a crucial task of the elected representatives and that, in fact, performing is similarly important in the context of grassroots social movement actors who lack institutionalized means of communicating with constituencies and attracting public attention. Therefore, social movement actors employ counter-performances such as demonstrations and strikes to impact political meaning-making practices and create alternative meanings (Apter, 2006; Eyerman, 2006). Students of contentious politics typically refer to such counter-performances as “contentious performances” (Tilly, 2008) and point to their constitutive power (Casquete, 2006). The present study provides new insights into how contentious performances contribute to constituting an event-focused protest movement in times of “lockdown.”

Further contributions to scholarship and knowledge concern the methodology and empirical results of this article: it makes a proposition on how to analyze political performances of control as discursive events based on the toolkit of qualitative-interpretive methodologies (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow, 2012). The comparison of a few key performances of control sheds light on some of the political styles in which control was performed and contested in Germany during the so-called first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, an original empirical dataset, including rich ethnographic data on the PEGIDA movement is generated, which provides novel insights into both institutional and grassroots politics. The analysis offers a basis for a nuanced understanding of the political situation in Germany ahead of the 2021 parliamentary elections and elaborates on the contested meaning of democracy during the COVID-19 pandemic (Afsahi et al., 2020; Merkel, 2020; Rapeli and Saikkonen, 2020; Stasavage, 2020; Engler et al., 2021).

Materials and Methods

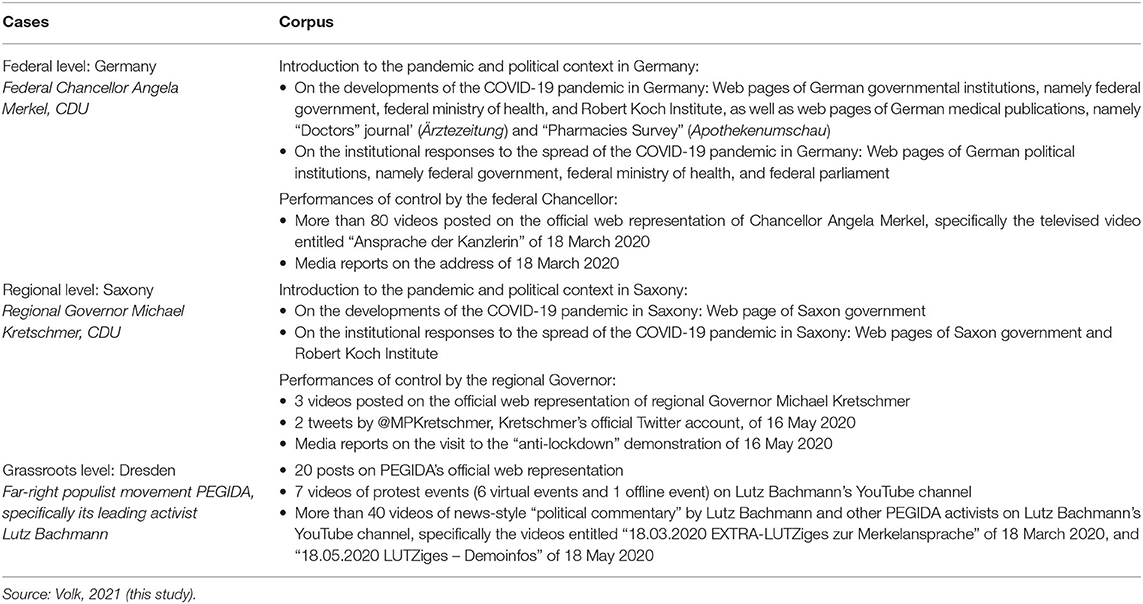

The underlying research strategy of this study is the qualitative-interpretive analysis and comparison of a small number of cases within the broader German political context (Moses and Knutsen, 2007; Landman, 2008). Rather than constructing the cases according to the standardized logics of “most similar” and “most different system designs” (Przeworski and Teune, 1970), the analysis first looks at them as single cases, and then puts them into dialogue, tracing how they relate to, respond to, and contest each other. As summarized in Table 1, these cases are political actors at different hierarchical and (non-)institutional levels of the German polity. The cases were selected according to the theoretical and empirical interest in first instances of institutional performances of control, and second instances of counter-hegemonic contestation of institutional control and counter-performances. The selection moreover aims to constitute a coherent geographical framework of closely intertwined national, regional, and local levels of politics. The time period of the study ranges from mid-March to mid-May 2020, that is the dates of the imposition to the partial lifting of the coronavirus regulations in Germany, which are understood as the turning points in the institutional and public crisis response.

On the institutional side, the two cases selected are that of Chancellor Angela Merkel as head of the federal government and that of regional Governor Michael Kretschmer as head of the government of the Bundesland of Saxony. Both Merkel and Kretschmer belong to the conservative governing party Christian–Democratic Union (Christlich–Demokratische Union, CDU). The contrast between national and regional representatives of the government draws attention to the peculiarities of political crisis management and institutional competition in a federal context. In turn, on the grassroots side, the case in focus is the most persistent far-right populist movement in Germany, “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident” (Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes, PEGIDA), as the challenger and counter-performer. PEGIDA constitutes an interesting case not only due to its persistence even during the crisis, but also because as a far-right populist movement (Druxes and Simpson, 2016; Vorländer et al., 2018; Volk, 2020), its populist style has a propensity to “perform crisis” (Moffitt, 2015) and to claim to represent truly democratic politics (Volk, forthcoming; Mudde, 2007). Finally, the case of Saxony constitutes a pertinent example for a federal state due to its allegedly unique political culture (Jesse, 2016), and the geographic origin of PEGIDA in Dresden, the capital of Saxony, thus allowing for geographically coherent analysis.

In line with the non-essentialist theoretical approach to politics, the methodological framework is informed by qualitative-interpretive methods of data generation and analysis (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow, 2012). Specifically, it draws from ethnographic and performative approaches to politics to allow for an in-depth analysis of the performative contexts of speech and discourse (Alexander and Smith, 2010; Saward, 2010; Aronoff and Kubik, 2013; Rai, 2014; Moffitt, 2016; Rai et al., 2021). Specifically, it gathers and analyzes data relating to the performers, including their habitus, modes, and (emotional) tones of communication, scripts, stages, intended audiences as (imagined) constituencies, and modalities of transmission. Therefore, the article uses an ethnographic approach to data generation, gathering a corpus that allows the exploration of political meaning in its performative context. In particular, the corpus was generated by conducting an online (or virtual) ethnography, which uses the internet both as a source of data and a field itself while still striving for immersion into the culture under study (Hine, 2017). The ethnographic approach to data generation particularly relates to novel forms of real-time participant observation of protest events set in the virtual sphere.

The analytical framework furthermore draws from discourse theory associated with the Essex School and its recent applications, which emphasizes the constant (re-)articulation and transformation of meanings in discourse (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985; Marttila, 2019). Building upon a constructivist ontology and interpretive epistemology, this approach takes interest in the meanings of political “objects” and the processes of meaning-making. Based on the notion that language is not only descriptive but constructs the meaning of the world and constitutes objects as such (Austin, 1962; Laclau and Mouffe, 1985; Butler, 1990), this interpretive, non-essentialist stance proposes that meaning is not natural and inherent in objects. Rather, meaning emerges in processes of interaction between social actors and is purposefully articulated in performance. In Laclaudian vocabulary, the central concept used to analyze the transformation of meanings is the “empty signifier,” referring to terms invested with antagonistic meanings by different actors over time. “Floating” within and across discourses, empty signifiers typically constitute points of contestation. Also, they are key to understanding specific discourses because, as “nodal points,” they order individual articulations into a more coherent discursive framework. Applying the discourse-theoretical framework to this study, the idea of “(controlling) democracy” is identified as a core nodal point characterizing political performances of control during the so-called first wave of the pandemic and “lockdown” in Germany. Conceptualizing democracy as an empty signifier, the comparative framework aims to develop a deeper understanding of the coinciding articulations, antagonistic meanings, and dynamic transformations of the floating signifiers “control” and “democracy” among and between discourses.

Results

The comparative analysis identifies and then focuses on a few (counter-)performances of control included in the corpus, which qualify as key discursive events due to their disruption of the “normal” and their exceptionally broad reception as public events (Handelman, 1998; Wagner-Pacifici, 2017). The individual cases do not only constitute interesting examples and structurally important discursive events as stand-alone instances of performances of control but gain further analytical weight due to their inter-relatedness. The performances identified for the three actors are the following: first, for Chancellor Merkel, the key performance of control was the televised “address to the nation” of March 18, 2020. Second, for Governor Kretschmer, the most important performance was a broadly mediatized and publicly discussed visit to an “anti-lockdown” demonstration in Dresden on May 16, 2020. Finally, for PEGIDA, key counter-performances of control were the immediate reactions of a leading activist to the institutional performances by Merkel and Kretschmer, and the organization of both virtual and later physical protest events.

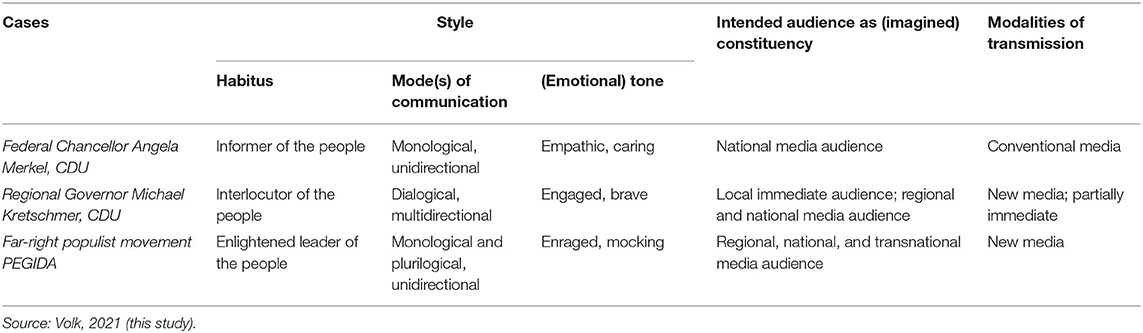

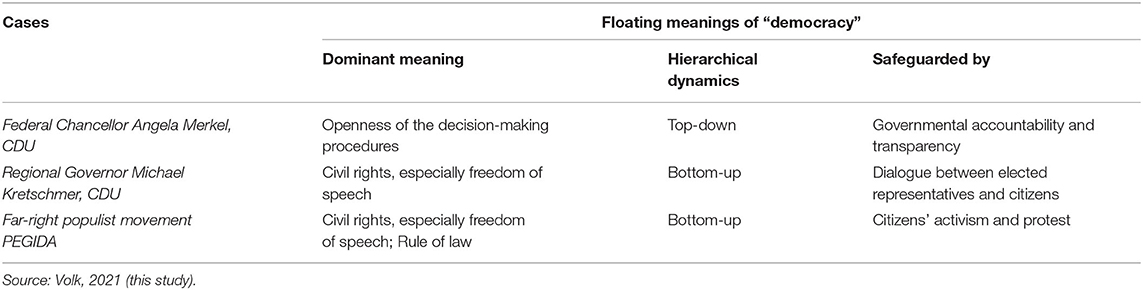

Informed by an ethnographic perspective on data generation (Alexander and Smith, 2010; Aronoff and Kubik, 2013), the following sub-section briefly outlines the development of the pandemic in Germany as a whole and Saxony as a Bundesland in order to imbed the instances of institutional and grassroots (counter-)performances of control into the broader pandemic and political context of spring 2020. The subsequent in-depth analysis provides further insights into the performances themselves. To begin with, the types and styles of performing control are explored by conducting disciplined, interpretive case studies (Odell, 2001) of the performers and performances, thus acknowledging their important structural differences. The comparison of the individual cases reveals some of the similarities and differences in the performative styles of the three studied actors (summarized in Table 2). The second part of the analysis concentrates on the antagonistic articulations of the floating signifier of “democracy” among and between discourses (summarized in Table 3). While the rich corpus of this study would yield even more detailed results regarding the individual cases, the comparative framework demands the focus to be only on a few examples in the latter part of the analysis.

Table 2. Overview of research results: political styles of performing control in Germany during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, mid-March to mid-May 2020.

Table 3. Overview of research results: articulations of “democracy” as an empty signifier in German political discourses during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, mid-March to mid-May 2020.

Introduction to the Pandemic Context

The first known case of an infection with the new coronavirus was registered in Germany on January 27, 2020. In the following weeks, the number of infections first increased only slowly, and then skyrocketed: whereas the daily infection numbers stayed low in February, they increased to more than 1,000 new cases per day by mid-March and more than 5,000 new cases per day by the end of the month. Accordingly, the total number of infections in Germany reached more than 1,000 individuals by March 9, 10,000 individuals by March 19, 50,000 individuals by April 2, and the preliminary maximum of more than 64,000 individuals by April 7. Similarly, the number of fatal cases of infections with the new coronavirus rose rapidly: after the first two deaths registered on March 9, daily death figures reached the preliminary maximum of 250 on April 10. At the same time, the situation started to ease: first, the numbers of daily new infections dropped, falling below 1,000 infections on April 27 and stagnating at 300–400 infections by the end of May. After May 23, the total number of active cases dropped below 10,000 and stabilized at around 5,000 active cases throughout the summer. Yet, in the fall of 2020, Germany again saw a rapid rise in daily infection numbers, reaching the total number of more than 370,000 active cases per day at the end of the year.

The institutional response to the arrival of the new coronavirus in Germany was immediate, but initially rather small-scale. Indeed, throughout February, the institutional response primarily concerned the isolation of the first German patients infected with the new coronavirus, and the return of German citizens located in the Chinese city of Wuhan, the epicenter of the pandemic at that time. Only from late February 2020 onward did the federal institutions expand and coordinate their efforts to contain the spread of the virus. The first step was the launch of a taskforce on February 27. Gathering members from both the ministry of health and the home office, the taskforce met repeatedly over the following days and weeks, determining measures on both internal and external matters. One of the major concerns was about preparing the German healthcare system for the expected rise of the lung disease, i.e., COVID-19 and the possible shortages of equipment such as ventilators and professionally trained medical staff. Hence, among the first measures were restrictions to the export of medical equipment and the appeal to hospitals to reschedule planned operations and recruit more staff. In addition, the taskforce decided upon measures aiming to lower the infection rates. These comprised the ban of public events with more than 1,000 participants and restrictions to cross-border travel, namely a general travel warning for German citizens and limited access to Germany for non-nationals, both issued by the foreign ministry in mid-March.

A legislative response followed only on March 23, when the German federal parliament adopted the first “Law to protect the population in the event of an epidemic situation of national concern.” The law clearly marked the spread of the new coronavirus as a national rather than regional or municipal issue. Comprising both limited and unlimited provisions, it prescribed several measures of “social distancing,” namely the ban of public events, the temporary closure of gastronomic services, and limitations to the individual right to freedom of movement. Some 6 weeks later, in mid-May, the parliament adopted a second law of the same title, prescribing further measures to respond to the coronavirus pandemic, namely the better protection of vulnerable groups, strengthening of administrative processes of tracing infections, and financial compensations for the medical staff.

With regard to the geographical spread of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic across Germany, a high level of variety in daily infection numbers among the German federal states characterized the spring of 2020: whereas some towns and districts had already registered infections in February and developed into local and regional hotspots in March and April, other Bundesländer registered cases only in March and had extremely low levels of infections throughout the entire first wave. Indeed, most of the early infections were located in the two southern states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg and associated with returning ski tourists from South Tirol and Austria. The early hotspots of coronavirus infections mostly grew out of folkloric events such as the Carnival and beer festivals in North Rhine-Westphalia and Bavaria. The most famous hotspot of infections nationwide was the district of Heinsberg in the Rheinland: following a mass Carnival celebration, Heinsberg registered case numbers far above the national average and introduced strict local curfews to contain the spread of the pandemic. In contrast, the pandemic arrived only a few weeks later in the eastern and northern states, which also had comparatively low levels of cases throughout the first wave of the pandemic and the summer. The federal state of Saxony registered the first case on March 2, 1 month after the new coronavirus arrived in Germany. Throughout the entire first wave, the numbers of daily new infections among the ~4 million inhabitants of Saxony stayed comparatively low: new infections never exceeded 250 per day during spring and dropped to <50 new cases per day by late April.

Due to the important legislative competencies of the German federal states, the regional administrations were responsible for the majority of measures to contain the rise of infection rates among the population, especially during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to a temporarily chaotic legal situation, as the Bundesländer adopted rather different measures: for instance, whereas Bavaria called the state of emergency, other federal states were opting for a more moderate response, especially if infection rates in their region were low. In response, starting from March 12, federal and regional levels of government took up a series of coordination meetings in which nationwide regulations were devised to be implemented by the federal states in “corona protection decrees.” Yet, a certain amount of legal uncertainty persisted throughout the crisis, as regional governments regularly opted out of federal decisions. Thus, the details of contact regulations, curfews, and quarantine rules, and the modalities of school closures, differed widely among the federal states.

The Saxon government did not call the state of emergency in 2020, yet its response to the crisis was timely and comparatively strict, particularly when taking the low infection numbers into account. From March 10, a special taskforce, gathering members from the regional ministry of health and, later on, from the home office, took measures to contain the further spread of the coronavirus in Saxony. With this aim, it consecutively banned the organization of public and private events, regulated the visits to old age homes, introduced certain types of curfew, and, on March 23, closed schools and kindergartens. In national comparison, the prescriptions for individuals to only leave their house based on “relevant reasons” and to stay within a radius of 15 kilometers was especially strict. Saxony also introduced fines of up to €25,000 and imprisonment for not complying with the measures.

From March 31, the Saxon government issued a series of “corona protection decrees” that spelled out the details of the restrictions to public and private life and the fines to comply with the measures. In these decrees, Saxony went ahead of other Bundesländer in introducing measures that would later concern all federal states. For instance, the second decree introduced hygiene and safety measures such as the obligatory wearing of masks in public transport and in shops. The decrees issued from April 30 slowly eased the measures. This time, Saxony was one of the first federal states to reverse some of the regulations. For instance, Saxon schools and kindergartens were the first to reopen in Germany. The Saxon population re-gained the right to be in contact with ever more individuals and households. In mid-May, cultural institutions such as theaters, cinemas, and concert halls, as well as the tourism industry were allowed to reopen with targeted concepts to ensure hygiene.

Types and Styles of Performing Political Control

The comparative analysis of the (counter-)performances of control by the three individual actors, namely the federal Chancellor Angela Merkel, the regional Governor Michael Kretschmer, and the protest movement PEGIDA, discloses some of the different styles of performing and contesting political control during the so-called first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. The individual performances bear similarities and differences in terms of the styles of control, specifically in relation to the habitus, mode of communication, and (emotional) tone of performances, the intended audiences as (imagined) constituencies, and the modalities of transmission (summarized in Table 2). With regard to these dimensions, the individual performers sometimes contrast sharply, and at times resemble each other to a surprising extent.

Performing Control at the National Level: Angela Merkel

Notwithstanding her role as the highest executive, Angela Merkel was neither the first nor the only performer of control during the COVID-19 pandemic at the national level. Initially, Merkel did not perform by “showing of a doing” (Gluhovic et al., 2021) but delegated the responsibility to react to the situation to the federal minister of health. Merkel started to assume an active role in governmental action and communication by attending a press conference at the ministry on March 11, 2020, finally demonstrating her “political presence, activity, progress, and engagement” (Gluhovic et al., 2021, p. 15). From that day onward, Merkel stayed one of the main performers of control during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Throughout 2020, she issued a multitude of statements in press conferences, during question time in sessions of the federal parliament, and also in audio and video podcasts.

The most widely disseminated and undoubtedly the most extraordinary measure taken to perform control during the crisis was Merkel's “address to the nation,” a video message broadcast on public TV channels in Germany at prime time on March 18. The stage, reach, and modalities of transmission (Saward, 2010; Moffitt, 2016) were utterly remarkable: for the very first time throughout her long-term chancellorship, Merkel chose the format of a video message widely broadcast on public television in order to communicate to the German population in the context of a major crisis. The Chancellor had not communicated an issue directly to the citizens during the global economic and financial crisis of 2008, the crisis of nuclear energy associated with the Fukushima catastrophe in 2011, or the European “refugee crisis” of 2015/2016. Rather, the format of the “address to the nation” had been reserved to her traditional TV greetings for New Year's Eve since 2005. The exceptional character was moreover demonstrated by the modalities of its transmission: the video interrupted the scheduled program of the German public TV channels, forcing the audiences, imagined as “the German people” to watch the speech of the Chancellor while waiting for delayed media contents.

Merkel's message “to the people” was a 13-min prerecorded video whose format, setting, and visual aspects impressively constructed control, statehood, and democratic legitimation, thus acknowledging some of the most fundamental goals of performing executive control in a representative democracy (Rai, 2014; Rai et al., 2021). The message visually constructs the notion of statehood due to its setting in the building of the state chancellery at the center of Berlin. Two large flags, one German and one European, are placed on the left side of Merkel, marking the speech as both German and transnational discursive event. In the background, the building of the federal German parliament with its glass cupola appears, visually framing the speech as a democratic act through the iconic appeal to the principal democratic symbol of the country. Whereas these formal and visual aspects remind of the past New Year addresses, the video also breaks with some of the previously established norms. Counting 13 min, it is nearly twice as long as the typical New Year's Eve address. Moreover, it is set in bright daylight, contrasting with the vespertine atmosphere of her past video messages. Due to the lighting and plain outfit of Merkel, the mood is not festive or solemn, but rather serious and concerned.

Regarding argumentation and speech, the Chancellor articulates governmental control with affirmative statements relating to the functioning of the German state, public institutions, the economy, and the supply of goods. Toward the beginning, Merkel plainly asserts that “The state will continue to function.” Countering popular fears of a shortage of food stuff, she stresses that “supply will, of course, be secured,” explaining that “if the shelves are emptied for a day, they will be refilled.” Merkel also attempts to strengthen popular trust in the German healthcare system, arguing that “Germany has an excellent healthcare system, possibly one of the best in the world. This can give us confidence.” With regard to the detrimental impact of the so-called lockdown on the economy, she emphasizes that “The federal government is doing everything possible to absorb the shock for the economy—particularly to keep jobs,” and ensures the flexibility of the government: “as government, we will keep checking what can be corrected … we will stay agile to be able to change course and react with different instruments at all times.”

Yet, the scripts of the performance of Merkel give away some of the limits of institutional claims to control, revealing the constructed rather than the factual character of political control during the crisis. In fact, the text modules articulating control alternate and interact with modules qualifying the ability of the government to stay in control. Among these qualifiers are rather rational and emotional modules, both spread out throughout the speech. The rational passages explain and evaluate the situation and aim to convince the population to support the governmental measures, thus creating a dense net of diagnosis, explanation, prognosis, and appeal. For instance, in the first sentences of her speech, Merkel asserts that “It is serious. Therefore, take it seriously. Since German Unity, no, since the Second World War, the country did not face a challenge in which it depended so much on common solidary actions” (diagnosis), unfolding that “as long as there is no therapy against the coronavirus and no vaccine, there is only one guideline to the actions: to slow down the spread of the virus, to stretch it over months and to gain time” (explanation). In this context, she predicts that “we will pass this task” (prognosis) and immediately underlines the need for individuals to cooperate by qualifying her hopeful statement: “if all citizens understand this task as their task” (appeal).

The emotional qualifiers to government control express empathy with the German population and thank people directly involved in responding to the situation. Merkel assures her understanding of the severity of the regulations, referring to them as “dramatic,” “difficult,” and “hard.” In this context, she recognizes the self-employed and small business owners among the working population as the groups particularly negatively affected, alongside children and students. She also appeals to the empty signifier of democracy, framing democratic rights as a historical achievement of the German state. In particular, she draws on a historical comparison, involving her experience as a former citizen of the socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR), to underline the exceptionality of the measures implemented by the government: “let me assure you: for somebody like me, for whom freedom of travel and movement were rights fought for hard, such restrictions are only justifiable in the situation of absolute necessity.” Moreover, Merkel addresses direct thanks to the professional groups working throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, most importantly, the medical staff in the hospitals whose efforts she denotes as “tremendous,” and also supermarket employees “who do one of the hardest jobs that currently exists.”

Finally, the scripts of the performance of Merkel involve various text modules that emphasize the universal value of human life, draw attention to the vulnerability of society and construct Germany in this light as a solidary community. For example, Merkel demands to regard infections and deaths not as “abstract numbers of statistics,” but as “a father or grandfather, a mother or grandmother, a partner, human beings.” She creates an immediate connection between the universal value of human life and Germany as a community of individuals: “we are a community in which every life and every human being counts.” According to Merkel, this community must build on mutual solidarity, hence she argues that “just like indiscriminately each and every one of us can be affected by the virus, everybody must now help … by not thinking for only one moment that he or she does not really make a difference. Everybody counts, our common effort is necessary.” In addition, Merkel highlights the vulnerability of the German society, stating clearly that “the epidemic shows us how vulnerable we all are, how dependent on the considerate conduct of others.”

The modalities of transmission and reception in the days and weeks following its publication mark TV address of Merkel as an exceptional performance of state control during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Both conventional and new media widely discussed the speech over the following days. A broadcast of the German public radio station Deutschlandfunk called the address “Merkel's best speech,” comparing it with celebrated speakers and speeches such as Barack Obama or Winston Churchill whose speech on “blood, toil, tears, and sweat” to the British House of Commons on May 13, 1940 (Jahn, 2020). In December, Merkel's address received the award of “speech of the year” by the Tübingen-based Institute for Rhetoric Studies. Evaluating dimensions such as argumentative structure, stylistic quality, and impact, the jury referred to the address as “an impressive appeal to responsibility and community which links the clear presentation of complex scientific insights to empathy and political prudence” (Seminar für Allgemeine Rhetorik, 2020). On top of that, the address had its own entry on the online encyclopedia Wikipedia by the end of March 2020.

Performing Control at the Regional Level: Michael Kretschmer

Beyond the national level, performances of control of Merkel were complemented and, at times, rivaled by regional performers of control. In the Bundesland of Saxony, the main performer was the comparatively young regional Governor of Saxony, Michael Kretschmer. Being in office only since 2017, Kretschmer was nevertheless experienced in dealing with political and social crises at the outbreak of the pandemic: during his 15-year service in the national parliament as a deputy of Görlitz, the easternmost city of Saxony, he had witnessed the disruption of German institutional politics following the rise of the far-right anti-establishment party AfD. The AfD had been especially successful in Saxony, winning over his electoral district of Görlitz.

Michael Kretschmer constituted himself as a public performer of control from mid-March onward. In particular, he delivered three speeches in front of state and federal legislative bodies, namely the Saxon parliament on March 18 and April 9, and the Bundesrat, the German “upper house,” on May 15. These speeches explained and justified governmental measures taken to contain the spread of the coronavirus and the new “opening” taking place in Saxony from mid-May. In contrast to these speeches, which were not widely received, the most outstanding performance of control was the visit of Kretschmer to a so-called anti-lockdown demonstration taking place in Dresden on May 16, 2020. Accompanied by a few bodyguards and a small camera crew, Kretschmer publicly “showed a doing” (Gluhovic et al., 2021), namely by spending about 1 h at the demonstration located in a large public garden close to the city center of Dresden. At the site, he actively engaged in conversations with some of the ~400 demonstrators. He performed his interest in a casual exchange with the demonstrators by arriving and moving around on a bike and by not using a face mask.

The visit constituted an attempt to regain control over the increasing polarization of Saxon society in light of the growing popular contestation of the regulations. Indeed, “anti-lockdown” demonstrations against the restrictions had regularly been taking place all over Germany since late March (Teune, 2021), and eventually also set off in Saxon cities, including the regional capital Dresden. Media and political observers compared the rather opaque mobilization with the anti-immigration protest wave of 2015 and 2016 (Gathmann et al., 2020), pointing to the possible threat of increasing societal polarization and the further rise of far-right AfD in Saxony and beyond. Hence, at the demonstration and later in both traditional and new media, the Governor staged himself as the first politician to enter into dialogue with the growing anti-establishment coalition: initially at the demonstration itself, later that day on the ministerial Twitter account, and finally in media interviews. The relevant tweets give insights into how Kretschmer performed statehood at the site. For instance, he wore an outdoor jacket featuring the Saxon corporate design, namely the phrase: “this is Saxon style” (“So geht Sächsisch”) on bright green ground, embodying his claim to represent Saxon statehood.

A widely shared video included in his tweets provided a stage for the performance of statehood and governmental accountability of Kretschmer in the context of justifying the regulations. During the publicized exchange with a middle-aged male demonstrator, the Governor based his argument for the restrictions on an emotional comparison with the developments of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. In response to the question by the protestor of how Kretschmer dealt with being responsible for allegedly increasing anxieties among children, the regional Governor asserted: “i am so glad that there are no big convoys of trucks with corpses here like in Bergamo … Every decision we had to take was bitter. I could not sleep for many nights … But I did not want to have the responsibility for … being in a similar situation due to our actions.”

The reception of performances of Kretschmer by his immediate and media audiences, imagined as the local and regional population, was rather ambiguous. At the demonstration itself, Kretschmer received both praise and confronted contempt: while some demonstrators recognized his “effort to listen,” others called him names and harshly asked him to leave, thus rejecting his claim to control as illegitimate. In the hours and days following the visit, demonstrators, commentators, political allies and opponents, and social media users publicly discussed Kretschmer's performance of control on both traditional and new media platforms. Many commentators, including members of his Saxon governing coalition, criticized Kretschmer for creating a stage for far-right extremists and conspiracy theorists. At the local level, however, Kretschmer's action yielded a rather positive echo, accepting his claim to control. The local newspaper evaluated the visit as a genuine attempt to start a dialogue with people holding different opinions, fitting in with the authentically dialogical political style of Kretschmer (Winzer, 2020).

Contestation and Counter-Performances of Control: PEGIDA

Institutional performances of control in Germany during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic did not stay uncontested. Besides the previously mentioned “anti-lockdown” protests against the regulations, some actors among the “established' protest scene continued their activism during the pandemic and lockdown. One of these actors was PEGIDA, the largest far-right populist protest movement in Germany. PEGIDA is a grassroots organization managed by a small team of activists from the eastern German city of Dresden since 2014. At its core are public protest events on the streets and squares of Dresden, namely fortnightly demonstrations. The demonstrations are usually non-violent events (Volk and Weisskircher, forthcoming) consisting of a couple of speeches and a march. Mobilizing against a multicultural society and the political establishment, PEGIDA's ideology is representative of the broader populist far-right in Europe (Druxes and Simpson, 2016; Vorländer et al., 2018; Volk, 2019; Caiani and Weisskircher, 2021). In the past, PEGIDA had reached extraordinary mobilization successes with up to 25,000 participants, on average male and middle-aged members of the working population. In the months before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the regular events gathered around 1,500 demonstrators and special events, such as anniversaries, up to 3,000 participants.

As an organization that had principally relied on and constituted itself through counter-hegemonic public protest for more than 5 years, the restrictions to mass events posed a major challenge for PEGIDA's activism, and the activists complied with the regulations only reluctantly. Indeed, PEGIDA insisted on organizing a scheduled demonstration on March 16, 2020, despite the previous ban of public events by the Saxon state government as well as the attempts of the city administration to convince PEGIDA to suspend the event. Notwithstanding the final decision of the municipal authorities to forbid the demonstration, leading activist Lutz Bachmann announced a “patriotic week” full of “spontaneous appearances” in Dresden and surroundings on his YouTube channel. Eventually, however, PEGIDA was unable to stage contentious performances that week due to the absence of leader Bachmann, who got stuck in his residence on the Spanish island of Tenerife following the travel bans in Europe.

Hence, in the following weeks of spring 2020, PEGIDA staged virtual counter-performances to articulate counter-hegemonic political meanings (Eyerman, 2006; Tilly, 2008). The virtual counter-performances both contested the legitimacy of institutional politics, in particular, governmental control during the crisis, and claimed control for grassroots actors like PEGIDA and their allies. They included live broadcasts of political commentary by Bachmann and other PEGIDA activists as well as virtual protest events, which replaced the typical demonstrations.

Bachmann's Enraged Contestation of Institutional Control

One of the first instances of contestation of institutional control by PEGIDA was Lutz Bachmann's response to Chancellor Angela Merkel's televised “address to the nation” of March 18, 2020. His immediate response was a 10-min live broadcast on his YouTube channel, namely an enraged monolog denying the expertise of the Chancellor to deal with the crisis and governing a country writ large. The particular staging marks Bachmann's response as a spontaneous reaction rather than a rehearsed performance: set in the outdoor spaces of “a friend's place” in Tenerife, the YouTube video features Bachmann dressed in a polo shirt in front of a swimming pool and a sling chair, with the roofs of southern-style houses and a few meridional trees in the background. Despite the leisure time scenery, Bachmann's response constitutes a counter-performance of control in that he is “showing a doing,” namely creating counter-hegemonic meanings regarding both institutional politics and PEGIDA as their challenger. His performance reached 18,000 views on YouTube by the end of 2020, more than twice that of “regular” videos posted that month.

Bachmann's counter-performance to governmental control is in line with PEGIDA's previous populist, notably anti-elitist discourse and style (Vorländer et al., 2018; Volk, 2020). Indeed, Bachmann blames the Chancellor for “having run down” the German healthcare system, educational sector, and public defense, and secondly, letting the economy “crash” in the context of the pandemic. He claims that Merkel lacks basic knowledge of the market, private enterprise, and economics in general, rejecting the rationale of the governmental measures as “halfhearted” and eventually detrimental to the economy, particularly for the self-employed and small businesses. He articulates his anger by using strong, emphatic language, and expressive gestures and mimics, including some instances of mockery of Merkel's style of speech and gesture: “each crisis which this woman tackled until now became worse at the moment when she took over control. We saw this in 2015, we saw this before … it always went completely wrong, and this time it will happen exactly the same.”

Specifically, drawing from the repertoire of populist articulations of the empty signifier of “the corrupted elites” (Mudde, 2004), Bachmann's performance denies Merkel the moral integrity to successfully take control of the crisis and governmental affairs in general. Principally, he suspects her of artificially prolonging the lockdown in order to conceal her “past failures” concerning the healthcare system, as well as to delay parliamentary elections and to gain time to “refurbish her image as a great crisis manager.” In addition, he incriminates her for her “audacity,” “lack of conscience,” and “callousness” to thank the medical staff rather than doubling their pay. Also, he blames her for “panic-mongering” based on her statement that it was yet unknown how long the pandemic would last and how many deaths it would produce. Not least, he maintains that Merkel would accept bribes by large companies, suggesting she has “a deal” with the telecommunications service Skype based on her reference to the provider as a means to stay in contact with other individuals during the lockdown.

Typical for populist counter-performances to representative claims (Saward, 2010; Moffitt, 2016; Volk, 2020), Bachmann proposes himself as a PEGIDA activist and eastern German citizen as an expert and therefore a superior performer of control in the situation of crisis. He suggests introducing an even stricter lockdown comparable to other countries, arguing that: “if you take measures and supposedly take this so seriously like her, then you do proper measures in one go, like other countries are doing it, like China did it, like Italy does it with curfews, like Austria does it, like Spain—I am stuck here!—exactly like they are doing it, and that's it.” Bachmann draws on PEGIDA's eastern German roots to argue that the German population will be able to act as a solidary community during the period of strict lockdown and curfews: “everybody really has to stand together for 4 weeks then. Solidarity within the people will then be needed. And this solidarity does exist … at least in central Germany (Mitteldeutschland) … There is still cohesion, the people will help each other … and then this whole story will work out fine.”

Bachmann staged yet another virtual counter-performance of control in reaction to the Saxon Governor's visit to the “anti-lockdown” demonstration in Dresden on May 18, 2020, which is 4 days after Kretschmer's controversial performance of control. Again in the form of a live YouTube broadcast, Bachmann re-articulated his critique of institutional politics. This time, he chose a more professional setting, staging his performance in front of an empty wall, which usually served as the backdrop to his videos of “political commentary.” Re-articulating his claims to the moral superiority of grassroots activism vis-à-vis the moral inferiority of institutional politics, he criticized Kretschmer for not having worn a face mask and rejected his justification to show his respect to the demonstrators as a “lame excuse.” In the video, Bachmann mentions the regional Governor of Saxony as a negative example in order to construct PEGIDA as a more responsible political actor, appealing to their supporters to properly cover their noses and mouths at the occasion of the first post-lockdown demonstration scheduled for the early evening of May 18. With this aim, he also underlines that PEGIDA's aims go beyond the critique of corona regulations, as they include the “protection of the rule of law and civil rights in Germany” alongside the opposition to migration.

PEGIDA's Counter-Performances

Besides Bachmann's live broadcasts contesting institutional control, PEGIDA's major means of performing grassroots control in the context of the crisis was the staging of virtual protest events in April and May 2020. Purposefully designed and well-rehearsed, these so-called “virtual marches through the living rooms of the patriots” publicly showcased the dedication and persistence of the movement during and beyond the period of “lockdown.” Replacing the originally planned demonstrations on the streets and squares of Dresden, these contentious performances highlighted that PEGIDA was able to mobilize despite difficult context conditions. PEGIDA thus contradicted the many media and political observers who had long predicted the demise of the movement due to low participation numbers and negative media reports. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic offered PEGIDA yet another occasion to perform their long-term critique and counter-identity. Activists repeatedly expressed their pride by claiming that PEGIDA is “Europe's largest active civil movement” (website entry of 14 May 2020), despite pandemic and “lockdown.”

Similar to Bachmann's YouTube monologs, PEGIDA's counter-performances of control re-articulated previously used populist and especially anti-elitist discursive patterns to contest institutional claims to control. The virtual events developed the idea that the regulations were part of an elitist conspiracy against “the people.” With this aim, the meaning of the populist empty signifier of “the corrupted elites” (Mudde, 2004) was broadened, including not only the German political and media establishment but also the World Health Organization (WHO) and the founder of Microsoft, Bill Gates, one of the main donors of WHO. PEGIDA suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic was artificially created to enable the total surveillance and oppression of the population via the “corona-application” and “compulsory vaccination.” At a virtual event on April 13, activist Wolfgang Taufkirch asserted that: “the WHO plans to go from house to house and practically test everybody for corona … first of all, everybody's DNA will be taken, and second, inconvenient contemporaries can be removed if their test ‘happens' to be positive.” With regard to Bill Gates, he predicted in the same speech: “gates stands in for the total surveillance of individuals by the state and corona comes just in time … Gates views the coronavirus pandemic as the perfect occasion to further develop and apply the technology of microchips … mass vaccinations could contain a microchip-implant on which one's DNA will be readable, which everyone would have to get on the recommendation of the WHO and inconvenient critics could be removed.”

In addition, virtual protest events of PEGIDA also contained an invert dimension, namely the performance of control over its own long-term protest ritual. The activists performed control over the ritual by designing the virtual events in terms of structure and content as similar to the conventional demonstrations as possible, signaling the persistence of the “brand PEGIDA” in the context of crisis. For instance, the virtual events took place at about the same hour on the same day of the week. Also, their structure involved typical elements of the established protest events such as the movement “anthem” at the beginning, followed by several speeches by Bachmann, his co-organizers, and some guest speakers, as well as the German anthem as a closing act. Even the traditional march was represented in the virtual format, namely as a high-speed display of a video recording of the real-life march at a previous event. Another means of performing control were the modes of networking and coalition-building with other organizations. Specifically, PEGIDA refrained from building coalitions with the emerging Querdenken movement, preferring to strengthen existing networks associated with the German and European populist far-right. The guests at the virtual events were activists who had visited PEGIDA demonstrations in the past: three activists related to the German and Austrian branches of the Identitarian Movement, two authors and editors from “alternative news” outlets, three AfD politicians, and one politician of the Belgian far-right party Flemish Importance (Vlaams Belang). In contrast, PEGIDA did not invite the organizers of the Germany-wide “anti-lockdown” mobilization to the virtual events nor did they advertise their events, even though Bachmann recognized the protest wave as part of a “larger movement of patriots and resistance fighters.”

Contrasting National, Regional, and Grassroots (Counter-) Performances

The in-depth analysis of the cases exposes a high degree of variation among the actors in terms of performative styles. As summarized in Table 2, the performers chose different modes of communication, namely monological, dialogical, and plurilogical as well as unidirectional and multidirectional forms of communication; displayed emotional tones from being empathic and caring over engaged and brave to being angry and mocking; and performed different styles of individual habitus, including the habitus of the informer, interlocutor, and enlightener in their quest to perform and contest control. Additionally, the performances differed in relation to their intended audiences as (imagined) constituencies, reaching from local and immediate audiences to regional, national, and transnational media audiences, as well as their modalities of transmission, including both conventional and new media as well as direct forms of communication.

Unexpectedly, the comparative analysis shows not only that the institutional and grassroots actors performed control very differently but also that the two institutional actors differed strongly, even though they occupy similar executive roles within their respective levels of the German polity and belong to the same party, the conservative CDU. The two contrasting political styles both complement and contest each other as fundamentally different approaches to staging institutional control during the crisis. Indeed, Merkel's style of top-down “informer” based on a monological, unidirectional mode of communication “to the people” contrasts sharply with Kretschmer's style of bottom-up “interlocutor” rooted in a dialogical, multidirectional mode of communication “with the people.” Similarly, the Chancellor's empathic and caring emotional tone is quite different from the Governor's engaged, pro-active, and somewhat brave behavior. In line with her top-down attitude of “informer of the people,” Merkel's performance relied solely on the conventional medium of public television in order to reach a national constituency, which is the largest possible share of the TV-watching German population. In contrast, the regional institutional performer Kretschmer sought to reach more varied audiences, ranging from local demonstrators to a regional (Saxon) constituency and national media audiences. With this aim, he employed immediate interactions with both demonstrators and new media platforms.

At the same time, on the grassroots side of politics, PEGIDA's style of performing control bears unexpected similarities with institutional styles, particularly with the monological and unidirectional informer style associated with that of Merkel. First, PEGIDA staged the movement as an “enlightening” force that “uncovers” the lack of legitimacy of institutional performances of control and claims the role of an oppositional “leader of the people.” Also, despite his fundamental critique of the Chancellor, Bachmann's monological, unidirectional mode of communication is surprisingly similar to that of Merkel, namely excluding the possibility for exchange with fellow citizens or followers. Even though PEGIDA also uses a polylogical mode of communication in its counter-performances, the mode of communication stays unidirectional. The tone in which PEGIDA activists contest institutional control ranges from enraged to mocking, thus displaying a similarly high emotional involvement in the crisis as Merkel, although the emotional landscape differs strongly from that of the Chancellor.

With regard to the intended audiences of the performances of control, the comparison of the cases points to very different imaginations of the represented constituencies. While not at the core of the analysis of this article, the notion of imagined constituencies also sheds light on whom the actors regard as part of the social entity they seek to control. The performances by Merkel and Kretschmer appealed to, broadly speaking, German constituencies at the local, regional (Saxon), and/or national levels, suggesting that the two executives, according to their respective institutional roles, indeed sought to perform control over their national and regional electorates. In contrast, PEGIDA's counter-performances were addressed toward a transnational audience. Claiming to represent a European constituency (Volk, 2019, 2020; Caiani and Weisskircher, 2021), the imagined constituencies of PEGIDA's counter-performances included not only the followers of the international guest speakers from Belgium and Austria but also a vague notion of “Europeans” writ-large. The differences between institutional and grassroots politics seem to confirm the so-called renaissance of the nation-state during the COVID-19 pandemic in the context of institutional politics. In turn, grassroots actors such as PEGIDA carried on their activism in the transnational realm.

Performing Political Control of Democracy

The comparative analysis discloses that political performances of control in Germany during the so-called first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020 were closely linked to claims of safeguarding democracy. Indeed, both institutional and grassroots performances of control linked the pandemic to the concept and lived reality of democracy in contemporary Germany, suggesting to control the persistence and guarantee of democratic principles during the pandemic. With this aim, the actors framed their individual performances as “democratic acts” rather than “acts of crisis control.” Stylistically, they supported their claims to performing democratic acts by displaying political and state symbols such as iconic buildings (Merkel), corporate design (Kretschmer), and Germany's key legal text, the Grundgesetz (PEGIDA). A further key tenet of the claim-making performances was the allusion to the recent past of the country, namely the socialist dictatorship in eastern Germany, as a negative example for state organization and civil rights in the country (Merkel and PEGIDA).

In discourse-theoretical terms, the performances prominently articulated meanings associated with the empty signifier of democracy. Moving and transforming within and across institutional and grassroots discourses, the empty signifier turned into a nodal point of crisis discourses in that period. Thus, its specific articulations by the federal, regional, and grassroots actors bore a high degree of antagonism and contestation. The foregoing analysis shows that individual understandings of what constitutes democracy and democratic values widely differ among the cases. On the institutional side of politics, top-down and bottom-up understandings of democracy competed with each other. For the federal Chancellor, democracy relates to the top-down notion of governmental transparency and accountability: as a government, to be democratic entails providing free access to information. Merkel thus motivated her TV address asserting, “This belongs to an open democracy: that we make political decisions transparent and explain them; that we justify our actions and communicate them to make them understandable.” The regional Governor of Saxony, in turn, articulated the meaning of democracy as freedom of speech and deliberation, thus taking a bottom-up perspective closer to individual citizens. Hence, he framed his visit to the “anti-lockdown” demonstration as an attempt to strengthen democratic values by engaging in dialogue with the protestors. He made this claim explicit in the context of a media interview some days later, underlining that “We live in a liberal democracy. Here everybody can say his opinion and contradict the elected representatives. It would be wrong not to take these people seriously” (Gaugele and Kretschmer, 2020). In the same context, he proposed that the interaction with the growing numbers of critics of the “lockdown” was crucial to prevent further divisions in German society: “the number of demonstrators will increase if everybody who has a critical position is forced into a corner and excluded as an interlocutor.”

As a counter-hegemonic force within and against the German federal polity, PEGIDA rejected institutional claims to representing democracy during the COVID-19 pandemic, thus fleshing out previous movement discourse on the assumed lack of democracy, rule of law, and civil rights in reunited Germany (Volk, forthcoming). In both antagonistic and polarizing fashion, the movement propagated that democratic values do not lie with the elected politicians and denied both federal and regional authorities of having the legitimacy to be in control. Activist Bachmann's YouTube monologs and PEGIDA's virtual counter-performances of control construct the allegedly undemocratic federal and regional politics as examples of broader shortcomings of democracy in eastern Germany since the demise of communism. Typical of PEGIDA's established discursive strategies, the activists draw on a historical comparison of contemporary Germany with past dictatorships, evaluating the state of democracy as at least as bad as that during the Nazi and communist regimes. For instance, claiming that “we exchanged the rascals against full-grown criminals in 1989 and 1990,” Bachmann suggests that the contemporary political leadership suffers from lesser degrees of legitimacy than the leadership of the GDR. In a similar vein, he proposes that some of the oppressive structures of the GDR, including the state party and the secret service, have been reinstated in reunited Germany.

Tying in with the populist argumentation patterns of articulating and representing “the people” (Canovan, 2005; Laclau, 2005; Mudde, 2007), PEGIDA moreover offered itself as a truly democratic force and therefore as more apt to be in control than the elected representatives. Hence, PEGIDA defended a bottom-up understanding of democracy as individual civil rights and freedoms (Volk, forthcoming). In addition, the movement constructed the idea of the individual responsibility of German citizens for the safeguarding of democracy. Indeed, PEGIDA advertised the virtual events as “virtual marches for our constitution,” “for our freedom of speech,” and “for our civil rights.” The claim to represent constitutionality and civil rights was supported by the use of historical and political symbolism. For example, activist Taufkirch ostentatiously placed a copy of the German constitution, decorated with a black ribbon, in the background of his video on April 27. Similarly, he displayed the so-called Wirmer flag, the symbol of the anti-Hitler coalition around Graf von Stauffenberg, thus constructing a historical parallel with past resistance forces. In the same context, he called upon citizens to take responsibility for the fate of democracy in Germany, warning them about repeating mistakes made in the past: “if our fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers, who also followed a mad man without resistance exactly 87 years ago, were still alive, they would have started a revolution long ago, so this does not happen again. They would be ashamed of how a nation gives up what they fought and struggled for after the war and later after the revolution of 89, within 3 weeks and in a docile and apathetic manner.”

Discussion

This final section discusses the results of the comparative analysis of institutional and grassroots (counter-) performances of control in Germany during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic against the backdrop of recent research on democracy and populism in times of crises. These reflections underline how the discourse-theoretical perspective on performances provides more nuanced understandings of the relationship between the pandemic and democracy and emphasize the strength of the performative approach to politics in a situation of an ultimate lack of control.

Democracy and Populism in/During Crisis

Political literature has mostly pointed to the dangers that the COVID-19 pandemic posed to democratic systems worldwide. Both theoretical and empirical work highlights that the crisis had had detrimental effects on democratic systems across the globe (Afsahi et al., 2020; Stasavage, 2020; Engler et al., 2021). Most obvious is the temporary cutback in the democratic rights of citizens such as freedom of movement, expression, and assembly. At a systemic level, democratic states have struggled and oftentimes failed to uphold democratic decision-making processes in favor of a centralization of powers at the level of the executive (popularly referred to as the “hour of the executive”). Even though Germany, as an established democracy, was to expect a less severe impact than newer or weaker democracies (Rapeli and Saikkonen, 2020), scholarship enumerates a few significant effects of the pandemic on the German democratic system. Specifically, the crisis caused the regression of individual democratic freedoms and the loss of importance of legislative bodies in favor of the executive as well as science as a non-elected “semi-sovereign” (Hildebrand, 2020; Merkel, 2020; Ramadani, 2020; Engler et al., 2021). The decline of democratic decision-making processes was accompanied and possibly reinforced by the temporal “self-silencing of the opposition in both politics and society,” notably also of the media, leading to a wide acceptance of the “new normality” (Merkel, 2020). Arguably, these decisive changes to the democratic system have turned Germany into a “coronacracy” (in German: Coronakratie) (Florack et al., 2021).

Additionally, the literature discusses flourishing conspiracy narratives as threats to democracy (Gollust et al., 2020; Hafeneger et al., 2020; Vériter et al., 2020). The so-called “infodemic” or “political communication crisis” constitutes major threats to democratic societies across the globe. By spreading false information regarding the origin of the virus and the aims of vaccines, among other things, they reinforce distrust in state institutions as well as social polarization. Also in Germany, “fake news,” “alternative facts,” and conspiracy narratives flourished during the pandemic, both in the context of established far-right populist actors like the empirical case of PEGIDA in this study and also the massive anti-lockdown mobilization starting from April 2020 (Hentschel, 2020; Grande et al., 2021; Pantenburg et al., 2021). For instance, conspiracy narratives posited that the political establishment had purposefully installed a “corona-dictatorship” in order to attain personal benefits.

“Coronacracy” and/or “corona-dictatorship”? The results of the comparative analysis in this study contribute a possibly more nuanced perspective on the status quo of democracy in Germany during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. While democratic principles have undoubtedly been impeded, notably legislative decision-making processes and individual freedoms, this study's findings demonstrate that the crisis has contributed to a high level of politicization of the concept of democracy as such. Indicated by the antagonistic articulations of the empty signifier of democracy in both institutional and grassroots discursive contexts, it seems that the concept has been put on the agenda of political debates much more so than during previous crises. Most importantly, in the “hour of the executive,” long-term federal Chancellor Angela Merkel's performance of control underscored governmental accountability and transparency. In contrast, Merkel did not stage a TV address “to the people” to explain and justify her decisions during the last major crisis her government was confronted with, namely the “refugee crisis.” In 2015, she famously proclaimed “We will manage!” (Wir schaffen das!) in a press conference rather than rendering governmental decisions transparent to the population. Similarly, as civil rights and freedoms were legally restricted, regional Governor Michael Kretschmer discursively reinforced their value at the anti-lockdown demonstration and beyond, articulating democracy in terms of freedom of speech and dialogue between citizens and elected officials.

With regard to the articulation and antagonistic contestation of the concept of democracy, the German case arguably takes a rather unique position in the European and international context. In fact, around the world, public debates at the outset of the pandemic were dominated by biopolitical perspectives focusing on public health and life as such rather than democratic principles (Winter, 2021). Accordingly, the heads of states and governments of other large European countries such as the Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, French President Emmanuel Macron, and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Boris Johnson, did not appeal to democracy in speeches that were comparable to Merkel's TV address in March 2020 (Gobierno de España, 2020; Government of the United Kingdom, 2020; Le Palais de Elysee, 2020). Even in Sweden, the only European country not to introduce a “lockdown” in spring 2020, Prime Minister Stefan Löfven did not justify the course of the country with the argument of safeguarding democracy (Regeringskansliet, 2020). Raising political consciousness for the need to safeguard civil rights in the context of crisis, the salience of democracy generated by the constant (re-)articulation of the empty signifier might have beneficial consequences for the German democratic system in the long term: as the pandemic situation underlined that democracy does not exhaust itself in legal texts and institutionalized power structures, but needs to be publicly performed and contested, it might create openings for democratic renewal (Ramadani, 2020).

In addition, this study's findings contribute a more nuanced perspective on the concept of populism in times of crisis and ultimately make a claim for discursive-performative approaches to populism. This concerns the relationship between populism and liberalism in particular. Whereas populism as “democratic illiberalism” is commonly associated with the opposition to liberalism (or, the constitutional pillar of modern democracy) in favor of majoritarianism (Müller, 2016; Pappas, 2016), the discourse-theoretical lens is able to show how the empty signifiers of democracy and liberalism were articulated alongside each other in the populist discourse during the crisis. Indeed, rather than expressing opposition to liberalism and constitutionalism, the populist PEGIDA movement appealed to the safeguarding of democratic principles in conjunction with the concepts of constitutionality and rule of law. The activists thus articulated a certain reading of constitutionality, focusing on civil rights, as a core component of the democratic system even in times of pandemic. Common also in other spatial, temporal, and organizational contexts (Moffitt, 2017), the parallel articulation of theoretically distinct or incommensurable ideas manifests the explanatory power of constructivist discursive and performative conceptualizations of populism vis-à-vis the more static ideological or ideational approach (Laclau, 2005; Aslanidis, 2016; Moffitt, 2016).

Performing (the Lack of) Control

The results of the foregoing comparative analysis of institutional and grassroots (counter-)performances of control in Germany during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic moreover make a more general methodological claim for the performative approach to politics: as the further development of the crisis, notably the outbreak of additional infection waves and repeated “lockdowns,” revealed, the pandemic confronted administrations across the globe with a fundamentally uncontrollable situation. In Germany, the degree of complexity of decision-making in times of COVID-19 was seen as comparable to the period of the major regime change in 1989/1990 due to the high level of uncertainty (Korte, 2020). Arguably, the level of uncertainty is even higher during a global pandemic. Politics confront an ultimate lack of control vis-à-vis a highly infectious virus, and thus “being in control” of the pandemic can only be a political illusion (Sabrow, 2021; Vorländer, 2021).