10 things we learned about our human ancestors in 2020

Early humans slept around a lot.

Early humans left behind clues — footprints, chiseled rocks, genetic material and more — that can reveal our species survived and spread across Earth. These ancient people weren't so different from us; they traveled far and wide, hooked up with one another and even mined for natural resources (in this case, the reddish mineral ochre). Here are 10 things we learned about our human ancestors in 2020.

1. Mystery lover

Early humans (Homo sapiens) didn't sleep with just one other. About 1 million years ago, H. sapiens had several rendezvous with another mystery species, and our species still carries some of these genes today, a study in the journal PLOS Genetics found.

It's possible this mystery species was Homo erectus, but we may never know for sure because H. erectus went extinct about 110,000 years ago, and scientists don't have any of this species' DNA.

Read more: Mystery ancestor mated with ancient humans. And its 'nested' DNA was just found.

2. Oldest known human DNA belongs to cannibal

The oldest known human DNA belongs to Homo antecessor, a species that may have practiced cannibalism. And at 800,000 years old, it's a record breaker.

Scientists found the remains of six H. antecessor individuals in Spain in 1994, but it wasn't until this year that a team of researchers extracted DNA from one of these individual's teeth, using the proteins found in the enamel to determine the segment of DNA that coded them. The team then compared this DNA sequence with recent human tooth samples, and determined that H. antecessor is not a close relation. Rather, it was likely a sister species of an ancestor that led to modern humans.

Read more: World's oldest human DNA found in 800,000-year-old tooth of a cannibal

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

3. Early humans left stone "breadcrumbs"

When modern humans (Homo sapiens) left the Horn of Africa about 130,000 years ago, they trekked along the Arabian Peninsula. But which path did they take? Now, scientists have an idea, after finding sharp, human-crafted flint points in Israel's Negev Desert that are just like "breadcrumbs" marking an ancient route, according to ongoing research at the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Read more: Ancient stone 'breadcrumbs' reveal early human migration out of Africa

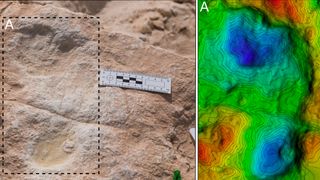

4. Footprints in Saudi Arabia

So, where exactly did humans walk on the Arabian Peninsula? Scientists know at least a few exact locations. Researchers have found 120,000-year-old human footprints among those of other ancient animals preserved in an ancient lakebed in the Nefud Desert of Saudi Arabia. These footprints are the earliest evidence of Homo sapiens on the Arabian Peninsula, the researchers said. During that time, the Arabian Peninsula was green and dotted with lakes, a hospitable place for migrating humans.

Read more: Prehistoric desert footprints are earliest evidence for humans on Arabian Peninsula

5. First Americans arrived 30,000 years ago

The first people to set foot in the Americas may have arrived 30,000 years ago, two new studies found. That's much earlier than researchers previously thought, with some scientists historically saying that the first Americans showed up as late as 13,000 years ago.

In one study, published in the journal Nature, the excavation of a remote cave in northwestern Mexico revealed human-made stone tools dating to 31,500 years ago. In the other study, also published in Nature, scientists took already-published data on early human activity in Beringia (the area connecting Russia to America during the last ice age), and entered them into an equation that modeled human dispersal. The model showed that early humans likely arrived in North America at least 26,000 years ago.

However, the Americas were sparsely populated that long ago. There wasn't a population boom until 14,700 years ago, as the last ice age was beginning to end, the latter study found.

Read more: First Americans may have arrived to the continent 30,000 years ago

6. Ancient diversity

Just like today, thousands of years ago the Americas were a diverse place. An analysis of four ancient skulls found in underwater caves in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo shows that these individuals looked nothing alike: one skull looked like people from the Arctic, another has European features, a third looks like early South American people and the last doesn't look like any one population.

The skulls date to between 13,000 and 9,000 years ago, just as the last ice age was ending, according to the study, published in the journal PLOS One.

Read more: Skulls from ancient North Americans hint at multiple migration waves

7. Sophisticated miners

Those same Mexican caves, which are now underwater, hid another secret, scientists learned in 2020. For years, divers have found the skeletons of ancient people, including the skulls mentioned above. This begged the question: What were ancient people doing there in the first place?

Now, new evidence suggests some of these ancient people were miners. About 12,000 to 10,000 years ago, ancient people mined the caves for the red mineral ochre and left signs of their work, including the charred remains of fires, stone tools and stone markers so they wouldn't get lost in the pitch black maze. Ochre was used for rituals and everyday activities, including possibly as insect repellent or sunscreen.

Read more: Ice age mining camp found 'frozen in time' in underwater Mexican cave

8. Toddlers have always been squirmy

More than 10,000 years ago, a woman carrying a toddler on her hip set down the child, readjusted, and picked up the child again as she continued her journey across the playa of what is now New Mexico.

Researchers found this woman's footprints, and those of the squirmy toddler, in White Sands National Park. At 0.9 miles (1.5 kilometers) long, this trackway is the longest late Pleistocene epoch double human trackway on record.

Read more: 10,000-year-old footprints show journey of squirmy toddler and caregiver

9. 'Ghost' population found in Stone Age children's genes

Four children who died young between 8,000 and 3,000 years ago in what is now Cameroon had secrets in their DNA. After analyzing the DNA from these ancient children's remains, scientists were surprised to discover a previously unknown "ghost" population of humans had contributed to these children's genomes.

About one-third of the children's DNA originated from ancestors that were closely related to known hunter-gatherers in western Central Africa, the researchers found. But the other two-thirds hailed from an ancient source in West Africa, including a "long lost ghost population of modern humans" that weren't known about until now, the scientists reported in the study, published in the journal Nature.

10. Polynesians and Indigenous Americans hooked up

Nowadays, dating apps can help people find partners. But 800 years ago, the Polynesians and Indigenous people of Colombia didn't have apps — they had boats, and apparently one of these groups boated to the other and hooked up.

When researchers looked at Polynesian DNA, they realized some carried a genetic signature similar to Indigenous Colombians. But it's unclear whether the Polynesians traveled to Colombia and then returned to Polynesia (with their Colombian-Polynesian children), or whether Colombians traveled to Polynesia, the researchers said.

"We can't say definitely who made contact with whom," study lead researcher Alexander Ioannidis, a postdoctoral research fellow of biomedical data sciences at Stanford University, told Live Science.

Read more: Polynesians and Native Americans paired up 800 years ago, DNA reveals

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.