Researchers Identify Mexican Wreck as 19th-Century Maya Slave Ship

Spanish traders used the steamboat to transport enslaved Indigenous individuals to Cuba

:focal(2342x1295:2343x1296)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/9c/499cc196-cbd2-463f-9825-75813f054447/inah_photo.jpg)

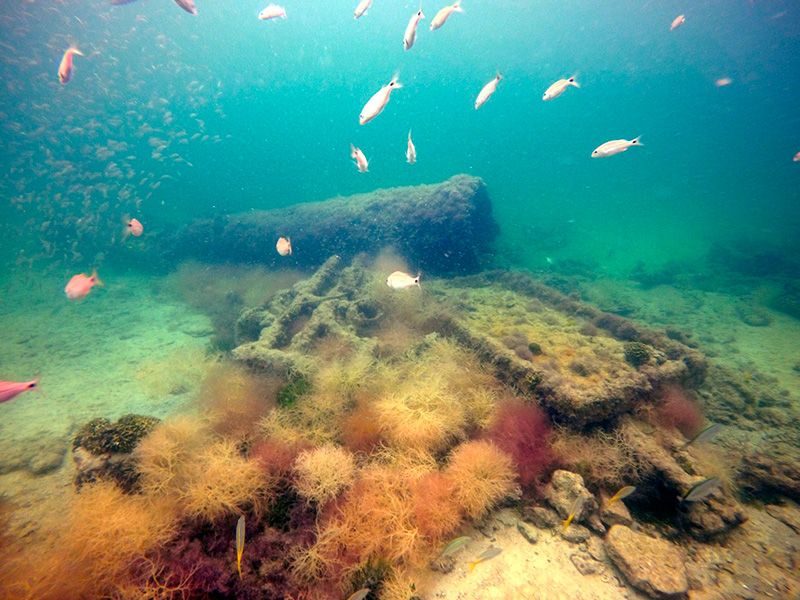

Off the coast of Sisal, Mexico, remnants of a 19th-century steamboat rest on the ocean floor, overgrown with marine plant life and slowly disintegrating.

When divers first discovered the wreck in 2017, its origins were largely a mystery. Now, after three years of research, Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) has finally identified the ship—and linked it to a violent chapter in the country’s history.

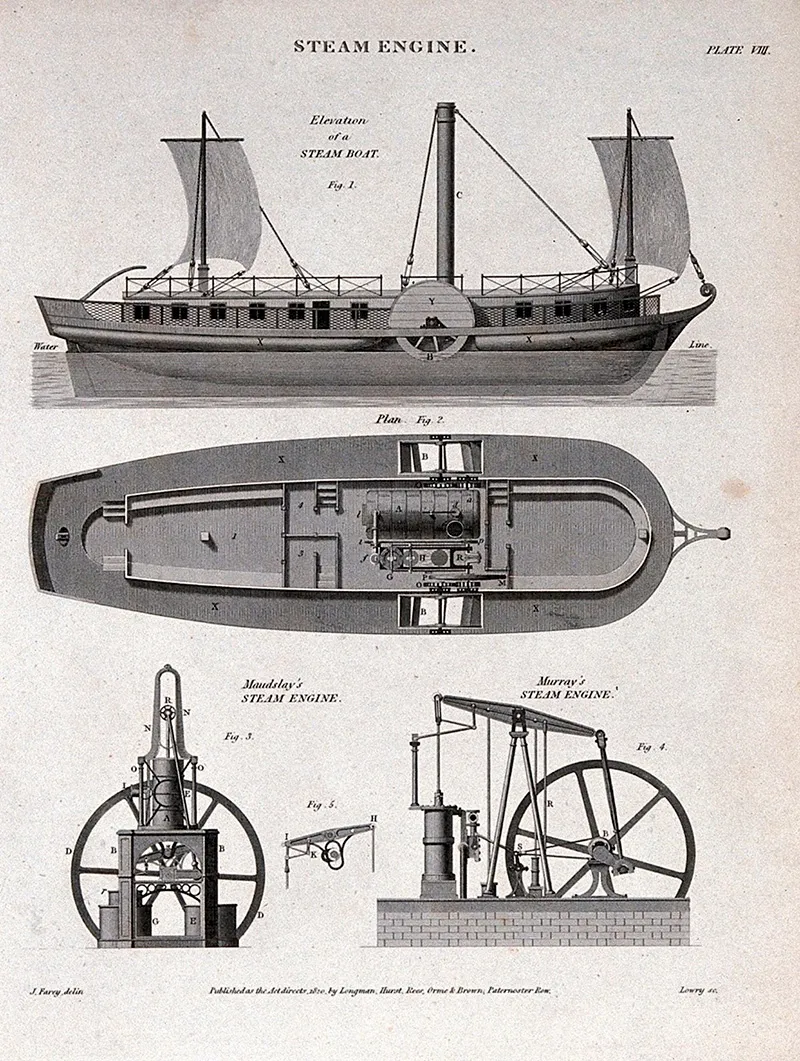

Historical documents suggest the vessel is La Unión, a steamer used to illegally transport enslaved Maya people during the second half of the 19th century, reports Mark Stevenson for the Associated Press (AP).

The find “speaks of an ominous past for Mexico, one that must be recognized and studied according to its context and time,” according to a statement.

In the statement, underwater archaeologist and lead researcher Helena Barba-Meinecke says the find marks the first time researchers have uncovered a vessel associated with the trafficking of Mayas.

Between 1855 and 1861, Spanish trading firm Zangroniz Hermanos y Compañía used La Unión to capture and transport about 25 to 30 Mayas to Cuba every month, notes Stephanie Pappas for Live Science. Upon arriving in Cuba, enslaved individuals were sold and forced to work on sugarcane plantations.

The ship was active as a slave vessel during the Caste War of Yucatán—one of the longest-running armed insurgencies of the 19th century. Per the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Maya peasants across the Yucatán Peninsula first revolted in 1847, sparking a war between the Indigenous community and the exploitative, land-owning, Spanish-speaking population.

Both sides “indiscriminately attacked the enemy population,” according to the Yucatan Times; by the time the clash officially ended in 1901, an estimated 300,000 people had died.

As INAH explains, many enslaved Mayas were captured combatants. Others were lured in by false papers promising a fresh start as settlers in Cuba.

La Unión was en route to to the Caribbean island when its boilers exploded on September 19, 1861, setting the ship’s wooden hull on fire about two nautical miles off the coast of Sisal. The explosion killed half of the 80 crew members and 60 passengers onboard, per the AP.

Researchers are unsure if any Maya people died in the disaster. Mexico abolished slavery in 1829, reports Alaa Elassar for CNN, so the traders likely would have concealed their illicit activities by listing any enslaved individuals on board as cargo.

In October 1860, authorities conducting a surprise search of La Unión found 29 captive Maya —including children between the ages of 7 and 10. But the raid had few lasting repercussions, and Mexico’s government only took more decisive steps to prevent human trafficking after the 1861 accident, according to INAH.

Wood from the bottom of La Unión’s hull has survived for more than a century, shielded from the elements by a layer of sand. In addition to traces of the hull, archaeologists surveying the site have discovered such artifacts as copper bolts, paddle wheels, iron compartments and even brass cutlery used by some of the ship’s wealthy passengers.

As the AP reports, researchers identified the wreck by comparing the damage to contemporary accounts of the accident. The team also spotted Zangroniz Hermanos y Compañía’s emblem on silverware found among the debris.

Barba-Meinecke tells the AP that INAH learned about the slave ship through oral histories passed down through generations of Sisal residents.

“The grandparents and great-grandparents of the inhabitants of Sisal told them about a steam ship that took away Mayas during the War of the Castes,” she says. “And one of the people in Sisal who saw how they led the Mayas away as slaves, told his son and then he told his grandson, and it was that person who led us to the general area of the shipwreck.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/d1/9ad1d279-c410-453a-ab92-b6a864d9eff5/foto8.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)