Each Advent, I do something unusual; I reread King Lear. Revisiting Shakespeare’s dark exploration of the dissolution of family, friendship, personality, and nation has become part of my annual rhythm. That might seem odd, particularly during this most difficult of years: With short winter days, and so much national, international, and personal pain all around us, who needs more darkness?

As a Christian, I do.

Reading Lear in Advent has taught me that seeing darkness is as crucial as seeing light. The pull Lear has on me is not temperamental; I am not particularly inclined toward despair nor attracted to melancholy. Rather, I see Advent as a season of waiting in the dark, but in hope of light. I’m compelled to attend to the in-between, to neglect neither and experience both, and to engage intensely in a season of absorbing perception and consideration.

Paying attention provokes and distills our humanity, but our distractibility is relentless, especially today, and it may be exceeded only by our capacity for denial. Our natural inclination is to look away from darkness, to pretend the shadows don’t exist—but they do. We need to find a way to look into the darkness without being overwhelmed by it, to stare in safety. Which brings me back to Lear. Being absorbed in the darkness of that story has taught me to breathe in the presence of darkness in our story.

Lear helps me see, feel, and measure life differently. For more than 40 years, I have found in Lear the vulnerable pulse and impulse of being human. The play condenses and dramatizes a tale of unraveling. The story is at once intimate and public—about the forms of self-destruction lurking inside a king’s power, and about the distorted pettiness that can undo life.

It’s about leadership exercised through the barrenness of lies, conniving, secrets, and charades. It’s a story of power and its impotence. The king cannot save himself, nor can the people around him. No one needs to strain to feel the heartbeat and the heartache of this drama. It may not be our tale, but it is our story.

Lear certainly makes for a different kind of Christmas reading. As the play unfolds, I can be choked by its jarring tragedy, the needless anguish of the tumbling, destructive descent toward death.

At the same time, I can see and feel it with some measure of dispassion because I know that this is precisely not my king, not my family, not my nation. And yet it is. My soul trembles as King Lear names and exposes the human greediness for love, combustibly combined with the treacherousness of our self-interest. It all hits rather too close to home, speaking not just to Shakespeare’s time but to ours, speaking not just to Lear’s struggles but to our own.

But why read Lear for this? Why not just walk out in the street, or read the newspaper, or scan the internet? Our human story can be viewed through many different lenses and angles. The distinct punch of Lear is the shocking immediacy of a play written more than 400 years ago, which intensifies rather than dilutes the force of its impact. Since it was finished in 1606, it has never not been relevant. Contemporary stories can be urgent and often compelling, but the seasoned crisis of Lear pierces more primitively, at a deeper and more elementary level. That is one reason it rings as it does.

In this year of the plague, we have experienced more isolation than we might have ever imagined. My wife and I live two blocks from my office, now silent, on the campus of Fuller Theological Seminary, now empty. I’ve visited it just twice since March, for a total of 10 minutes. Like many, but by no means all, I’ve had the privilege of a withdrawal from the physical presence of normality.

Still, I have especially tried to walk in the world this year with my heart and mind as wide open and engaged as they can be. It has been a year of pain and sorrow, rage and loss. I know and hear and feel much of that, which is why silence has never been a better or more necessary gift. Right in the midst of our collective groaning, the resilient, sacrificing beauties of being human have done more than flicker. They have revealed the gift of human being, a gift at once fragile and durable.

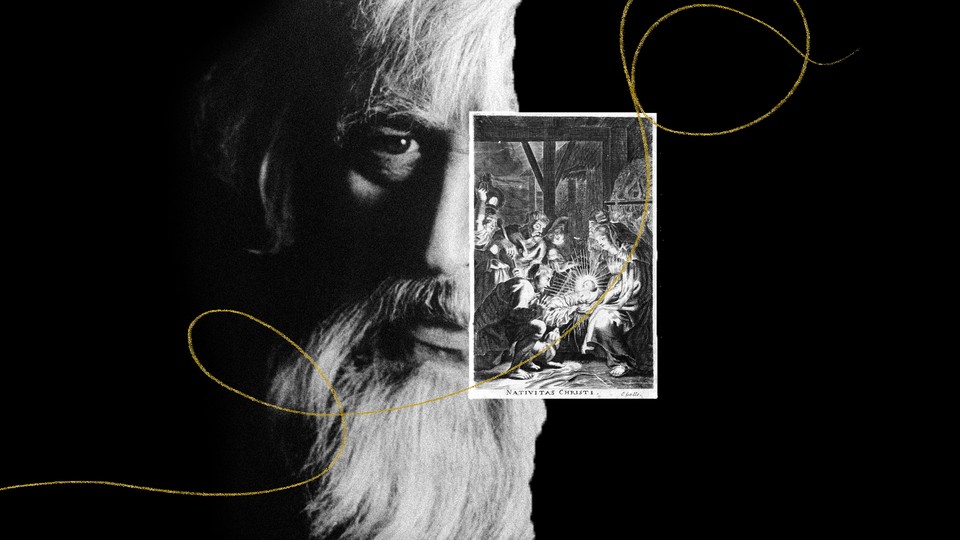

Lear’s lens on human being has been ground in such a way as to make it possible to see our troubles acutely, undistracted by hope. Reading the play each Advent exposes my raw, ongoing questions and perplexities. It also prepares me for the quiet shock of a vulnerable baby as God’s answer to human horror. Freshly wrapped in the depths of our personal and collective Lears, Christians for two millennia have greeted God’s breathtaking, swaddled self. Each story is as unremitting as the other. Sentimentality is swiftly squelched by both. When they are held in their audacious collision, I know Advent is done. The waiting and the darkness begin to give way to hope.

Christmas is here.