The Conservative government has a known mistrust of experts, but rarely do ministers fly in the face of their own commissioned research as starkly as the housing secretary did this week. On the very same day that Robert Jenrick triumphantly extended permitted development rights (PDR), allowing a range of building types to be converted into housing without planning permission, his own ministry published a report condemning the same rules for leading to “worse quality” homes.

After studying hundreds of new homes carved out from converted offices, shops, warehouses and industrial buildings, created between 2015 and 2018 through permitted development, a team of academics from University College London and the University of Liverpool found predictably grim results. The planning loophole had unleashed a new breed of tiny, dingy apartments, many barely fit for human habitation, with rooms accessed from long corridors, windows looking across internal atriums into other people’s rooms, and some bedrooms with no windows at all.

The research found that only 22% of dwellings created through permitted development met the nationally described space standards, compared with 73% of units created with full planning permission. They frequently came across studio apartments of as little as 16 square metres, less than half the size of the national standard of 37 sq m. Their research also found that the homes were eight times more likely to be located in the middle of a business park or industrial estate, while only 3.5% had access to outdoor space. Buildings converted to homes through permitted development, the researchers concluded, “do seem to create worse quality residential environments than planning permission conversions in relation to a number of factors widely linked to the health, wellbeing and quality of life of future occupiers”.

The academics submitted their findings in January, so it has come as a surprise that, six months later, the housing secretary has decided not to rein in permitted development rights, but extended them even further. It is particularly charged timing, given that planning rules are being relaxed in the name of “delivering additional homes more easily as part of the government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic”. At a time when the need for decent quality domestic space has been amplified, and the dangers of overcrowding magnified, the government is only making it easier for cramped, substandard homes to be built. Adding to frustrations over the delay, the new measures were announced one day before the parliamentary summer recess, and buried by the news of a damning report on Russia’s possible interference in the Brexit referendum.

“The new legislation fundamentally undermines the notion of a democratic, professional and accountable planning system,” says Dr Ben Clifford, professor at UCL’s Bartlett School of Planning, who co-led the research. “Not only will it continue to produce more tiny flats with poor living conditions, but it also means the developers are not required to provide any affordable housing or make any contributions to local infrastructure, like parks and playgrounds. It’s placing a huge burden on local communities, while at the same time making more profit for developers.”

Since 2015 more than 60,000 flats have been created through permitted development in England, with almost 90% coming from office conversions, representing a loss of tens of thousands of affordable homes, according to Shelter. “We were astounded,” says Robin White of the housing charity, in response to the new legislation. “This is a far cry from the prime minister’s promise to Build Back Better. And a far cry from the good quality, affordable social homes that this country so desperately needs.” Even the government’s own Building Better, Building Beautiful commission concluded that permitted development had inadvertently created “future slums”.

The president of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Alan Jones, describes the extensions of the policy as “disgraceful”, leading to more homes with rooms that will be “smaller than in budget hotels”. “There is no evidence that the planning system is to blame for the shortage of housing,” he says, “and plenty to suggest that leaving local communities powerless in the face of developers seeking short-term returns will lead to poor results.”

In what represents the most drastic change to permitted development rights since the planning system was introduced after the second world war, the legislation opens the door for a new generation of rabbit-hutch homes to proliferate unchecked. If an office or industrial building built before 1990 has been vacant for six months, it may now be demolished and replaced with a house or apartment block, without any planning scrutiny. Another amendment allows an additional two residential storeys to be added on top of existing buildings, while a third change combines everything from shops and restaurants, to gyms, health facilities, nurseries, offices and light industrial buildings into a single use class. As Rob McNicol, principal strategic planer at the Greater London Authority, tweeted: “This matters because you will now no longer need planning permission to change between these uses. The changes unpick a decades-long approach to planning for town centre uses. It is an untested nationwide experiment in laissez-faire town centre management.”

As Guardian investigations have shown, the substandard homes created by permitted development are often used to house society’s most vulnerable members, including as temporary accommodation for families on housing waiting lists. Harlow in Essex, where half the new homes created in 2018/19 came from office conversions, has become a particular flashpoint for the planning loophole. The buildings have seen incidents of domestic abuse, suspected drug dealing, alcohol-fuelled bad behaviour and reports of children who are frightened to go home and can’t sleep at night because they are “petrified”. Harlow’s Conservative MP, Robert Halfon, has described the policy as “a disaster”. “If there are not proper controls on quality,” he said, “and developers are allowed to build ghettos for people on the lowest incomes then we will have a repeat of what we’ve had in the first wave of permitted development.”

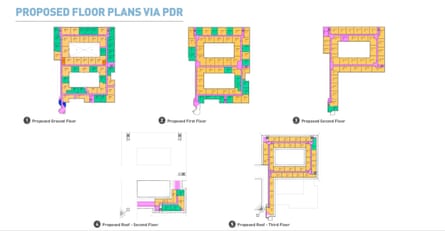

Harlow is not alone. Clifford’s research has highlighted a range of shocking examples, such as Central House and Maplehurst House in Crawley, which both contain 16-sq-m studio flats, some with no windows. Then there are the converted business parks, including New Horizons Court in Brentford, where 25 flats have windows just facing the central atrium space, 10m across from their neighbours, or the Central Business Centre in Neasden, with 20 studio flats sandwiched between a cement works and the North Circular Road. The largest permitted development project in the country is currently under way at the Parkview office campus in Bristol, which will see 467 flats created in a former supermarket headquarters, one building described on the architects’ own website as “doomed to be the housing complex”.

Julia Park, head of housing research at Levitt Bernstein architects, produced a report last year documenting a number of the worst examples of housing spawned by permitted development. She despairs at the latest legislation. “The government hasn’t learned anything from what office-to-residential conversions have produced so far,” she says. “The new rights will just lead to more of the same”. While the latest amendments include a requirement for “adequate natural light” in all habitable rooms, there’s no detail on what that actually means. “We’ve seen whole flats, and hundreds of habitable rooms that only have borrowed light from an internal atrium so have no view to the outside. Is that ‘adequate’?” As Park’s report noted: “Building regulations have never required a living space to have a window, not because it doesn’t matter, but because no one imagined that anyone would offer a home without one.” The regulations, it seems, were written in more innocent times, before the planning system was dismantled and our cities opened up to the market at any cost. Even the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, a powerful lobby group for the development sector, concurs: “Overall, office to residential PDR has been a fiscal giveaway from the state to the private real estate interests,” their 2018 report concluded (Pdf), “while leaving a legacy of a high quantum of poor quality housing.”

Park points out that permitted development rights have created a Kafkaesque situation whereby local authorities do not have the power to stop substandard homes being built, but they may be able to have them shut down once they are occupied. Through existing powers set out in the Housing Health and Safety Rating System, councils can serve an enforcement notice on any home that poses a severe risk to health, with insufficient internal space being among the recognised hazards. Park, who has been working with Leeds City Council to clamp down on a spate of very small flats, also has no doubt that a significant number of the new homes created through permitted development pose a serious hazard to mental health, and are therefore unfit for human habitation under the Fitness for Human Habitation Act, which came into force in March 2019. Shelter has also been advocating use of the act, although it cautions that it is not the solution. “We should not be relying on this act to fix fundamental quality and safety issues with housing that was created at most six years ago,” the charity said. “It goes without saying that these houses should have been up to scratch in the first place – which they would have been if they had the proper quality checks from the outset.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion