I spent most of my early years – aged one to three, say – being trodden on. “It was your own fault,” my mother explains. “You were too quiet. You used to stand by my feet, not making a sound, so I’d forget you were there. What toddler does that?”

I think the explanation lies in the fact that I wasn’t really a baby. I was a bookworm. For the true bookworm, life doesn’t really begin until you get hold of your first book. Until then – well, you’re just waiting, really. You don’t even know for what, at that stage – if you did, you would be making more noise about it and be less covered in court-shoe-shaped bruises. But it’s books.

My parents are northern. And Roman Catholic. They came down south in the late 1960s to look for work. My dad, to the bafflement of his upper-working-class family, wanted to work in the theatre. Mum, a recently qualified doctor, went with him.

My dad is a reader. There wasn’t much money in his family so there weren’t many books in the house, apart from a few precious bound collections of Boy’s Own comics. So it was to the Harris library in Preston that Dad took himself every week, working his way gradually through its offerings. My mother is not a reader. She is a doer. For most of my life, she was a gynaecologist, specialising in gruesome anecdotes and family planning (my mother is the only Catholic in history to have thrown off her upbringing utterly and never looked back).

When I was tiny I didn’t see Dad much because stage managing at the National Theatre takes you way past toddler bedtime. But my first real memory is of him tucking me in beside him on the long, brown floral sofa that sat on an orange carpet and opening a book almost as colourful as our sitting room. It was The Very Hungry Caterpillar, Eric Carle’s paint’n’tissue-paper collaged account of metamorphosis, fuelled by choice morsels of American culinary classics, into a butterfly.

Later came weekly trips to the local library. But those library books have not stuck in my mind. The ones Dad bought me, the ones I was able to keep and read and reread (and reread and reread and reread …) were the ones I loved. Adults tend to forget what a vital part of the process rereading is for children. As adults, rereading seems like backtracking at best, self-indulgence at worst. Free time is such a scarce resource that we feel we should use it on new things.

But for children, rereading is absolutely necessary. The act of reading is itself still new. A lot of energy is still going into (not so) simple decoding of words and the assimilation of meaning. Only then do you get to enjoy the plot – to begin to get lost in the story. The beauty of a book is that it remains the same for as long as you need it. You can’t wear out a book’s patience.

“There is hope for a man who has never read Malory or Boswell or Tristram Shandy or Shakespeare’s sonnets,” CS Lewis once wrote. “But what can you do with a man who says he ‘has read’ them, meaning he has read them once and thinks that this settles the matter?” The more you read, the more locks and keys you have. Rereading keeps you oiled and working smoothly, the better to let you access yourself and others for the rest of your life.

This is why it slightly frustrates me that my son, who is six, has never really had a favourite book. Even when he was very young and we were reading picture books to him, he never demanded the same one night after night, and he hasn’t become impassioned about any others since. There is hope for a boy who has never read The Gruffalo or Come Away from the Water, Shirley – but what can you do with one who has listened to them a handful of times and then buggered off to his Tonka trucks and thinks that settles the matter?

¶

As I got older, my dad was working long hours during the week, and in recompense had started coming home with a new book for me every Friday. Bliss it was to be alive every Saturday morning, when I would come down and find a shiny, pristine paperback on the breakfast table by my cereal bowl.

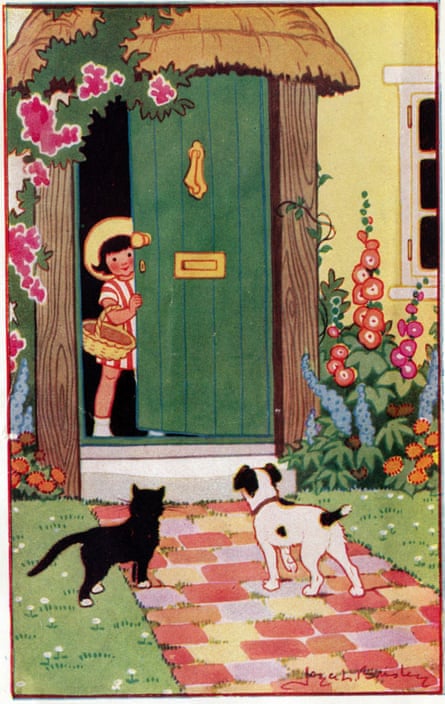

One day he brought home a book by an author called Joyce Lankester Brisley. Oh, Milly-Molly-Mandy. Until she came along, I didn’t know that either the countryside or the past even existed. But by the end of the first story in Brisley’s collection of tales (published in 1928) about the little girl in the nice white cottage with the thatched roof, I was wholly possessed by the desire to live in both. So great was my need for fuel for this fantasy that, for the first time ever, Dad bought me the rest of the series – five whole books! – at once. We were on holiday, which was already happiness enough, comprising as it always did two weeks with our beloved grandma in her flat in Preston, eating chip butties under lowering skies. Then suddenly, in flagrant contravention of all family tradition, there they were – Milly-Molly-Mandy books in lavish excess, waiting for me in a pile on the sideboard when I woke up in the morning. I am 43 years old as I write this, and still waiting for a moment of greater joy.

Every Milly-Molly-Mandy story is a miniature masterpiece, as clear, warm and precise as the illustrations by the author that accompanied them. They are crafted by a mind that understood the importance and the comfort of detail to young readers without ever letting it overwhelm the story. Maybe the creation of this calm, neat, ordered world was a comfort to the author too. In 1912 when Brisley was 16 her parents had – very unusually for the time – divorced, and she had been helping to support the family ever since by illustrating Christmas cards, postcards and children’s annuals. Those illustrations were, she once said, “bread and margarine for a good many years”.

Milly-Molly-Mandy began life as part of a doodle of a family group done on the back of an envelope as Brisley was, in a struggle familiar to many writers and artists, trying to come up with “a speciality” that would “earn something or other”. She then wrote a story to go with it. It was published in the Christian Science Monitor in 1925, followed by others, and young readers from around the world started to write in asking for more.

Milly-Molly-Mandy leads a delightful existence in a pink-and-white striped dress (red serge in winter, but the books are set in an eternal summer). Her time is largely taken up with buying eggs for Muvver and Farver (these spellings are the closest Milly-Molly-Mandy comes to subversion), stripping stalls at the village fete of home-made cakes, fishing for minnows in the stream and having picnics in hollow tree trunks with Little Friend Susan and Billy Blunt. You could ask for literally nothing more out of life, except, possibly, another dress.

She never seemed to do anything on laundry day and I suspected she had to sit naked on an upturned bucket until her single frock was dry again, which seemed a waste of a day’s gentle village adventuring. Who bought Grandma’s skeins of wool on those days? Ah – “skein”. This was my first meeting with the word. It looked strange then and it looks strange now. But I stomped off to ask Dad what it meant and so bent it to my will. It has not come in particularly useful since, but if you make usefulness your metric for life it will not be much of a life.

But words I seized on, always, gloating over new acquisitions like Silas Marner over his chestful of gold coins. I remember so many of our first meetings. I learned “Lumme!” from the Wombles, for which there has been even less call in the subsequent 30 years than there has been for “skein”.

Knowing what “blueing” was came from Ramona doing the laundry in one of Beverly Cleary’s ebullient books. Again, this has not been too useful, but proved an invaluable little nugget of knowledge when my passion for historical fiction and autobiographies of people who had lived in the ancient days of the 30s and 40s hit a few years later. The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster – well, where to begin? Among a billion other gifts, it gave me “dodecahedron”, “din” (via the Awful Dynne, Dr Kakofonous A Dischord’s genie assistant, whose grandfather the Terrible Raouw died in the Great Silence Epidemic). “Humbug” as something other than a sweet (which I’d learned about in Enid Blyton). The hitherto unknown “piccolo” and the “crooking” of a finger arrived in the very same sentence. As you might expect from a book set largely in a city called Dictionopolis, it was a treasure trove.

“Peculiar” in the sense of “particular” – that one came from Little Women. Jo had a peculiar sense of something that didn’t seem at all strange to me, so I applied to Dad and he explained that words can change their meanings over time. Who knew? Dad led me for the first time to the dictionary, where I found that some kind person had charted its evolution in minute detail for my delectation.

These, then, are the moments I adduce as evidence of the value and wonder of reading, when people ask me (as they often used to when I was younger, and still do) why I spend so long curled up with a book. It’s not the whole story, of course, but it’s a usefully tangible part if you’re preaching to the unconverted.

Reading about Milly-Molly-Mandy was a joy that transformed into an exquisite torture when I realised that although the Countryside did still exist (somewhere – I didn’t find out where until I was in my 20s and got a boyfriend who came from Kent. Apparently it was 30 minutes south of where I lived), the world in which these domestic non-adventures were set had already vanished. I would never live there, never buy that skein of wool for Grandma or wait for potatoes to bake in the village bonfire on Guy Fawkes night.

It all seemed deeply unfair. It was the first time a reading experience became infused with yearning – a lost art that makes most things sweeter. Milly-Molly-Mandy is proof that dictionary definitions lie. You can be nostalgic for a time you never knew. But maybe I was lucky. At least it was a way of life still culturally comprehensible to me. I’m about to start reading the books to my son and there is every chance that he will turn a bewildered gaze upon me, mutely mystified by references to village post offices, cottages unsold to developers and hollow tree trunks that haven’t been turned into branches of Tesco Express. He may, in an age that measures attention spans in nanoseconds, start writhing in frustration before we are even halfway through the chapter devoted to buying mustard and cress seeds for a penny or making a miniature garden in a china bowl.

I think there’s reason to hope not. I think the power of Milly-Molly-Mandy to comfort and compel will endure. The stories are simple, not stupid. They provide succour, not sentimentality. And if they spark a flicker of yearning within a child for a lost world, you can always point out that they only have to turn back to the first page for it to live again. That is what books are for.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion