There is an overwhelming expert scientific consensus on human-caused global warming.

Authors of seven previous climate consensus studies — including Naomi Oreskes, Peter Doran, William Anderegg, Bart Verheggen, Ed Maibach, J. Stuart Carlton, John Cook, myself, and six of our colleagues — have co-authored a new paper that should settle this question once and for all. The two key conclusions from the paper are:

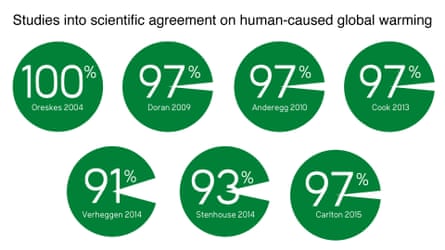

1) Depending on exactly how you measure the expert consensus, it’s somewhere between 90% and 100% that agree humans are responsible for climate change, with most of our studies finding 97% consensus among publishing climate scientists.

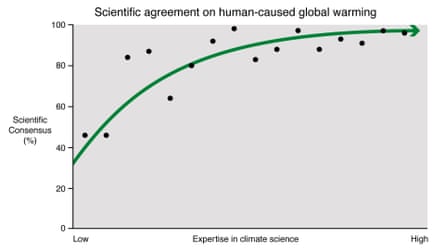

2) The greater the climate expertise among those surveyed, the higher the consensus on human-caused global warming.

Expert consensus is a powerful thing. People know we don’t have the time or capacity to learn about everything, and so we frequently defer to the conclusions of experts. It’s why we visit doctors when we’re ill. The same is true of climate change: most people defer to the expert consensus of climate scientists. Crucially, as we note in our paper:

Public perception of the scientific consensus has been found to be a gateway belief, affecting other climate beliefs and attitudes including policy support.

That’s why those who oppose taking action to curb climate change have engaged in a misinformation campaign to deny the existence of the expert consensus. They’ve been largely successful, as the public badly underestimate the expert consensus, in what we call the “consensus gap.” Only 12% of Americans realize that the consensus is above 90%.

Consensus misrepresentations

Our latest paper was written in response to a critique published by Richard Tol in Environmental Research Letters, commenting on the 2013 paper published in the same journal by John Cook, myself, and colleagues finding a 97% consensus on human-caused global warming in the peer-reviewed literature.

Tol argues that when considering results from previous consensus studies, the Cook 97% figure is an outlier, which he claims is much higher than most other climate consensus estimates. He makes this argument by looking at sub-samples from previous surveys. For example, Doran’s 2009 study broke down the survey data by profession – the consensus was 47% among economic geologists, 64% among meteorologists, 82% among all Earth scientists, and 97% among publishing climate scientists. The lower the climate expertise in each group, the lower the consensus.

Like several of these consensus surveys, Doran cast a wide net and included responses from many non-experts, but among the experts, the consensus is consistently between 90% and 100%. However, by including the non-expert samples, it’s possible to find low “consensus” values.

The flaw in this approach is especially clear when we consider the most ridiculous sub-sample included in Tol’s critique: Verheggen’s 2015 study included a grouping of predominantly non-experts who were “unconvinced” by human-caused global warming, among whom the consensus was 7%. The only surprising thing about this number is that more than zero of those “unconvinced” by human-caused global warming agree that humans are the main cause of global warming. In his paper, Tol included this 7% “unconvinced,” non-expert sub-sample as a data point in his argument that the 97% consensus result is unusually high.

By breaking out all of these sub-samples of non-experts, the critique thus misrepresented a number of previous consensus studies in an effort to paint our 97% result as an outlier. The authors of those misrepresented studies were not impressed with this approach, denouncing the misrepresentations of their work in no uncertain terms.

We subsequently collaborated with those authors in this newly-published scholarly response, bringing together an all-star lineup of climate consensus experts. The following quote from the paper sums up our feelings about the critique’s treatment of our research:

Tol’s (2016) conflation of unrepresentative non-expert sub-samples and samples of climate experts is a misrepresentation of the results of previous studies, including those published by a number of coauthors of this paper.

Consensus on consensus

In our paper, we show that including non-experts is the only way to argue for a consensus below 90–100%. The greater the climate expertise among those included in the survey sample, the higher the consensus on human-caused global warming. Similarly, if you want to know if you need open heart surgery, you’ll get much more consistent answers (higher consensus) if you only ask cardiologists than if you also survey podiatrists, neurologists, and dentists.

That’s because, as we all know, expertise matters. It’s easy to manufacture a smaller non-expert “consensus” number and argue that it contradicts the 97% figure. As our new paper shows, when you ask the climate experts, the consensus on human-caused global warming is between 90% and 100%, with several studies finding 97% consensus among publishing climate scientists.

There’s some variation in the percentage, depending on exactly how the survey is done and how the question is worded, but ultimately it’s still true that there’s a 97% consensus in the peer-reviewed scientific literature on human-caused global warming. In fact, even Richard Tol has agreed:

The consensus is of course in the high nineties.

Is the consensus 97% or 99.9%?

In fact, some believe our 97% consensus estimate was too low. These claims are usually based on an analysis done by James Powell, and the difference simply boils down to how “consensus” is defined. Powell evaluated the percentage of papers that don’t explicitly reject human-caused global warming in their abstracts. That includes 99.83% of papers published between 1991 and 2012, and 99.96% of papers published in 2013.

In short, 97% of peer-reviewed climate research that states a position on human-caused warming endorses the consensus, and about 99.9% of the total climate research doesn’t explicitly reject human-caused global warming. Our two analyses simply answer different questions. The percentage of experts and their research that endorse the theory is a better description of “consensus.” However, Powell’s analysis is useful in showing how few peer-reviewed scientific papers explicitly reject human-caused global warming.

In any case, there’s really no question that humans are the driving force causing global warming. The experts are almost universally convinced because the scientific evidence is overwhelming. Denying the consensus by misrepresenting the research won’t change that reality.

With all of the consensus authors teaming up to show the 90–100% expert consensus on human-caused global warming, and most finding 97% consensus among publishing climate scientists, this paper should be the final word on the subject.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion