In a muddy windbreak atop the Pennines, three fields over from Hadrian’s Wall, stands a 19th-century stone farmhouse where Michael Chapman has lived with his partner, Andru, “happily unmarried”, for the past 45 years. It is a dark winter night, and in their crimson-walled parlour, faces lit by the roaring fire, stories are being told. Chapman has just related the tale of the weathered Martin D-18 guitar in the corner of the room, played by Jimi Hendrix in Soho’s Les Cousins club, while Chapman slept, mid-set, in the car outside. Now the couple are recalling the night in Hull in 1969 when Nick Drake came to stay.

“He’d played the Haworth Arms [in Hull],” says Chapman, “and they’d hated him. He never never lifted his head between songs. I felt sick watching him, but what he played was incredible.” The Haworth Arms, for what it’s worth, now has Drakes Bar, “named after the famous folk musician who played here in the 60s”.

After the gig, Andru saw Drake standing alone under a street lamp. “I asked where he was staying,” she says. “He had nowhere. I said: ‘Come with us.’”

“Back home, he opened his guitar case, took out a beautiful Martin and three joints and I said: ‘OK I’m with him,’” recalls Chapman, smiling. “We played until five in the morning. The next day he was gone. That was our only meeting.”

This is how an evening with Chapman goes: reminiscences and memories, told with a dry-stone Yorkshire poetry, and red wine top-ups, the host assuming a quiet supporting role in the three-act dramas of the more famous.

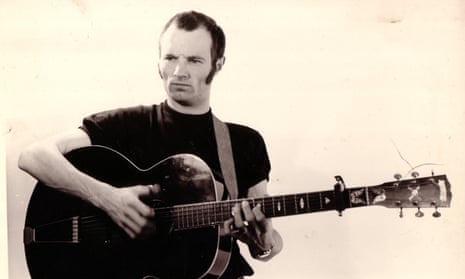

In theory, we’re here to discuss Chapman’s new studio album. Named 50, after his years on the road, and produced by the US guitarist Steve Gunn at Black Dirt Studio in Westtown, New York, it’s a rich, haunting, collection of forlorn love songs, apocalyptic picaresques and bewitching instrumentals that marks the latest stage in a remarkable career renaissance, fuelled by experimental solo guitar LPs, an impressive reissue campaign, and collaborations with Hiss Golden Messenger and the No-Neck Blues Band, that has seen this granite-faced 76-year-old Yorkshireman hailed by the likes of Meg Baird, William Tyler and Ryley Walker as the godfather of new cosmic Americana.

However, first we need to go back – to the working-class, self-taught musician from an industrial southern suburb of Leeds, who paid his way through art college playing in skiffle bands, strip clubs and jazz trios, plus a brief stint roadying for John Cage (“He did a recital at Leeds Art Gallery. I took him to the market to buy fish to put in his piano”). He later packed up his teaching job at Bolton College of Art, becoming a big name on the Cornwall acoustic scene, and signing to EMI’s hippy offshoot label Harvest in 1969.

His debut LP Rainmaker saw Chapman pigeonholed as part of the new London folk set, alongside Bert Jansch, John Renbourn and John Martyn – despite the fact that he lived in Hull, and refused to call himself a folkie – while its opening track, It Didn’t Work Out, with warm Gus Dudgeon production, Paul Buckmaster string arrangement, spiralling guitar and lyrics of self-reflexive introspection caught the ear of a 22-year-old pianist from Pinner called Elton John. Those same elements, except one, would be present and correct on Elton’s self-titled 1970 LP.

“Elton wanted me to join his band, but never asked me directly,” says Chapman, still bemused today. “Instead, Gus said: ‘Know any good young guitarists who play acoustic and electric?’ I recommended Davey Johnstone. Years later, I realised they were asking me.” Would he have stuck it? “Not sure. All I know is Davey Johnstone owes me a $2m house in California.”

A player of complex, dextrous flair, inspired as much by Grant Green as Woody Guthrie, Chapman knew a good guitarist when he heard one. For 1970’s Fully Qualified Survivor he recruited his neighbour, a parks gardener employed by Hull city council called Mick Ronson. This time, someone else was listening. “Mick was in this awful band called the Rats,” Chapman says. “I asked him to tour with me. He said: ‘I’m not leaving the Rats.’ So David Bowie turned up, took Mick, took the Rats, turned them into the Spiders from Mars.”

Here’s a fun parlour game: play Fully Qualified Survivor to an impressionable friend and tell them its a lost Bowie album, recorded just before Hunky Dory. It’s all there: the plangent acoustic guitars, the ornate strings, Ronson’s eastern-tinged Gibson wails; even Chapman’s surreal Dylan-esque ruminations, spinning on weed paranoia and delivered with a weary slur, point towards such labyrinthine Bowie head-trips as Quicksand and The Bewlay Brothers.

“Never heard Hunky Dory,” insists Chapman, “but everybody says it’s Survivor. Never asked him. Last time I saw David was in the mid-70s. I was going into our publishers to borrow 300 quid to keep my band on the road. He was borrowing 30 grand to keep his band on the road.”

The mid-70s were a time of hard work and hard play for Chapman. Floundering on Decca (“A label run by retired colonels”) Chapman subsisted on “booze, coke, loads of dope. It got very fuzzy.” He remembers a Sacramento gig with the US guitarist John Fahey, at which Fahey got a performing bear drunk on Guinness (“The bear grabbed the microphone like Rod Stewart … then collapsed with this giant, poisonous bear fart”), and budgets blown at Cornwall’s Sawmills Studio on 1976’s Savage Amusement, where drummer Keef Hartley nearly drowned, they drank St Austell dry, and Memphis producer Don Nix, “surviving on Quaaludes, cocaine and cognac”, dismantled all the Dolby noise-reduction modules, considering them “a commie plot”. The 80s were a thin blur, culminating in a huge heart attack in 1990 that put Chapman out of action for a year: “Everyone forgot about me. I signed to this record label called Planet. The guy operated out of a pub in Colne, Lancashire. A parallel universe. His friends were called things like Mick the Murderer, the Cat, and Cider Ronnie.”

A weird pub in Lancashire could be the fitting, tragic end for many a hedonistic 70s musician, but Chapman forged on, quietly rebuilding his career until a gig in Amherst Unitarian church in Massachusetts in 1998 revealed a very unlikely group of fans.

“Sonic Youth turned up,” says Chapman. “I’d heard of them, vaguely.” Over dinner, Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore explained that Chapman’s 1973 LP, Millstone Grit, a bare tapestry of lonesome blues and guitar atmospherics, informed by a disastrous 1971 US tour, had been the igniting spark in the genesis of their band.

“He blames the feedback extravaganzas on there for them forming,” says Chapman, still somewhat incredulous at the thought, embarrassed at the responsibility.

Chapman began corresponding with Moore, collaborating on various projects, culminating in his own noise album, 2011’s eerily beautiful The Resurrection and Revenge of the Clayton Peacock. Just to prove that was no fluke, in 2008 Chapman met another outlier fan, Virginia guitarist Jack Rose of psychedelic drone-folkers Pelt. The pair became fast friends, Rose introducing Chapman to fellow travellers such as Steve Gunn and the No-Neck Blues Band. Then, in December 2009, Rose died of a massive heart attack. Performing at memorials in Philadelphia and New York in February 2010, a distraught Chapman discovered a new generation of fans, drawn to the improvisational, experimental elements in his music, far more likely to associate him with John Fahey than Elton John.

“His 70s records were so ahead of their time,” Gunn told me, before I met up with Chapman. “There’s a panoramic feel to them that really resonates. But, unlike his contemporaries, there’s no ego, either in his music or as a person. He’s very humble, but still in there. He’s still present.”

Praise sits uncomfortably with Chapman, especially when there are still stories to be told, but he admits that recording 50 has unlocked something new.

“I thought there was nothing left in the tank,” he says. “Then, from the middle of nowhere, I started writing songs again. Now I feel like there are other things I want to revisit.”

Midnight chimes. Glasses are topped up.

“Now,” he says, “Did I ever tell you about the time I played bass for Wilson, Keppel and Betty?”

50 is out now on Paradise of Bachelors

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion