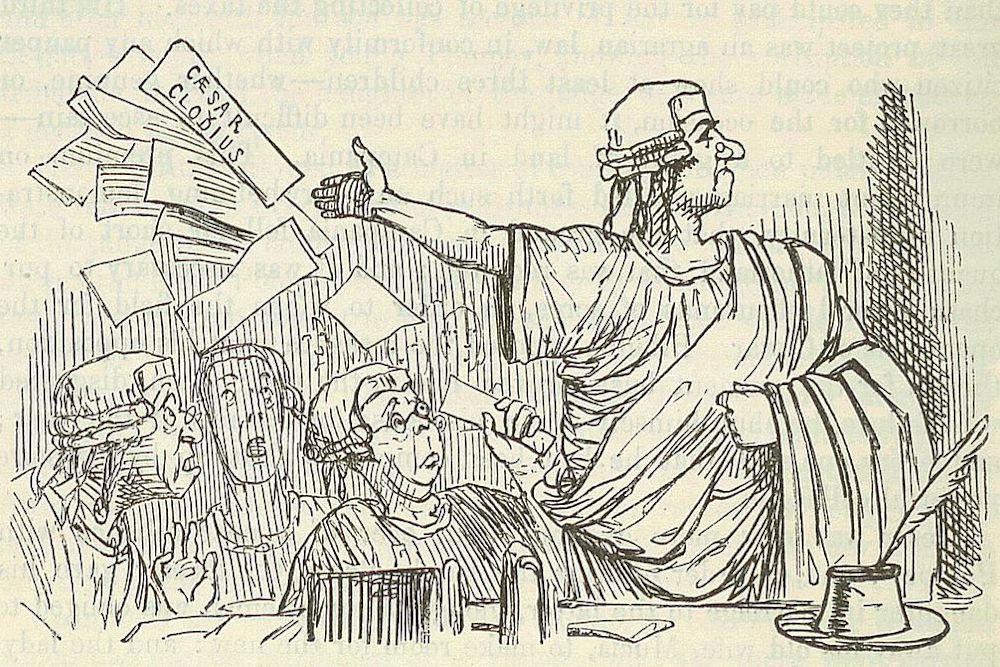

Caricature of Cicero depicted in The Comic History of Rome by Gilbert Abbott A Beckett. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

At some point in the early summer of 54 BC, the Roman statesman Cicero set to work on his most consequential work of political philosophy: De Re publica (On the Republic). This exploration of what the Roman Republic had become, and what it was supposed to be, looked backward and forward in Roman history—and continues to have important implications for anyone living in a republic today.

Cicero set De Re publica in the year 129 BC, a dramatic moment when Romans, for the first time in centuries, had begun to confront the consequences of political violence. In 133 BC, a mob had killed the tribune Tiberius Gracchus after he used a combination of threats and extra constitutional measures to push through a series of land reforms. Four years later, the damage from Tiberius’s recklessness had become clear, but Rome still had a chance to mitigate it. So Cicero chose this moment to stage a dialogue in which the age’s most prominent politicians, jurists, and thinkers debated the nature of an ideal constitution and questioned what would become of their Republic after “the death of Tiberius Gracchus had divided one people into two factions.”

Cicero emphasized that Tiberius’s tactics of intimidation and his willingness to disregard law set Rome on a very dangerous course. “If this habit of lawlessness begins to spread,” he explained, it “changes our rule from one of justice to one of force.” This made Cicero “anxious for our descendants and for the permanence of our Republic.”

Cicero’s fear grew in part out of what he believed the Republic to be: community property of Romans, who were bound together not by race or ethnicity but by a shared sense of justice and fidelity to law. Law, Cicero wrote, provided the foundations for just interaction between citizens. It established the channels through which political decisions passed. And, because Rome was a representative democracy in which citizens elected leaders and voted on the legislation they proposed, Cicero argued that the Roman Republic could last forever if it remained governed by law and administered vigorously by its citizens.

A state governed by violence had much dimmer prospects. At best, such a state might sometimes “seem as if it was at peace” because “men feared each other … but no one was confident enough in his own strength” to challenge his adversaries. A sort of stable anarchy emerged, and a balance of fear was the only thing that held back citizen violence. Such a polity was no longer governed by laws. It could not be considered a republic.

Cicero’s Rome “may retain the name Republic, but we have long since lost the actual thing,” he wrote in De Re publica. By 54 BC, the Republic “was like a beautiful painting whose colors were beginning to fade.” Romans have “neglected to refresh it by renewing the original colors” and “have not even taken care to preserve its shape.” In other words, complacency was undermining the Republic.

During the three years it took Cicero to finish his De Re publica, Rome degenerated into something that looked a lot like the republic of violence the work described. “Murders happened every day,” the historian Cassius Dio later observed, “and [Romans] could not even hold elections” as regular street fighting between factions paralyzed political life. The most notorious of these, a battle on the Appian Way between gangs loyal to the politician Milo and his rival Clodius, led to Clodius’s death in January of 52. Clodius’s supporters then carried his body into the Roman senate house, heaped the chamber’s benches into a pyre, and incinerated both the corpse and the structure.

Cicero hated Clodius so much that, in the midst of writing De Re publica, he agreed to serve as an advocate for Milo at his trial. Constant threats and heckling from Clodius’s supporters interrupted Cicero’s planned remarks. He later published what he wished he would have said, a speech in which Cicero asserted that violence had to be used against Clodius because he was a “man whom we were unable to restrain by any laws.” In the heat of the moment, even Cicero defended vigilante justice.

Order returned to Rome in 52, only after the Senate called upon the powerful general Pompey the Great to secure the city. They granted him an “army and levy of troops,” a force that made Pompey more frightening than any of the petty leaders of Rome’s political gangs. It is hard to imagine more compelling evidence that Rome had descended from a Republic of laws and become a city stabilized by fear.

But, as Cicero understood, all it takes to destroy the balance of fear is a figure who is willing to try.

And, in Rome, Julius Caesar was that figure.

Caesar had spent much of the 50s conquering Gaul with a powerful and loyal army. But his command was due to expire at the end of the year 50. Caesar and his allies in the capital tried to negotiate an agreement that would protect him from politically motivated prosecution if he dismissed his troops, but the leaders of the Republic lacked the will to come to an agreement with him.

More importantly, the Republic’s leaders also lacked the capacity to reassure Caesar that any agreement he made would be observed. “Compelled by its terror at the presence of Pompey’s army and the threats from his friends,” the Senate ordered Caesar to disband his army or be declared an enemy of Rome.

When the Senate followed through on this threat in January of 49, Caesar went before his troops and told them that political activities permitted by law were “now branded as a crime and suppressed by violence.” The soldiers responded that “they were ready to defend their commander” and his allies “from all injuries.” This declaration—that violence, not law, governed Rome—began the series of civil wars that ended the Republic.

The United States now approaches the tipping point between a republic governed by law and the polity of violence, governed by mutual fear, that Cicero described over two millennia ago. Political violence courses through our streets as groups of demonstrators fight each other. The president and his political allies express public support for a young man who shot two protestors. It might be tempting to applaud Americans we agree with when they attack those with whom we do not, as Cicero did. But the distance from Cicero’s defense of Milo’s vigilantism to Caesar’s appeal to his troops is quite short. Neither vigilante justice nor armed insurrection can exist in a Republic whose citizens share a common purpose and respect for laws.

Cicero himself said so in one of the very last things he ever wrote before soldiers loyal to Mark Antony and the future emperor Augustus killed him, hanging his hand and head on the speaker’s platform in the Roman Forum. “Nothing,” Cicero proclaimed, “is more destructive to civilizations, nothing is so contrary to law and justice … than governing through violence in a Republic.”

Send A Letter To the Editors