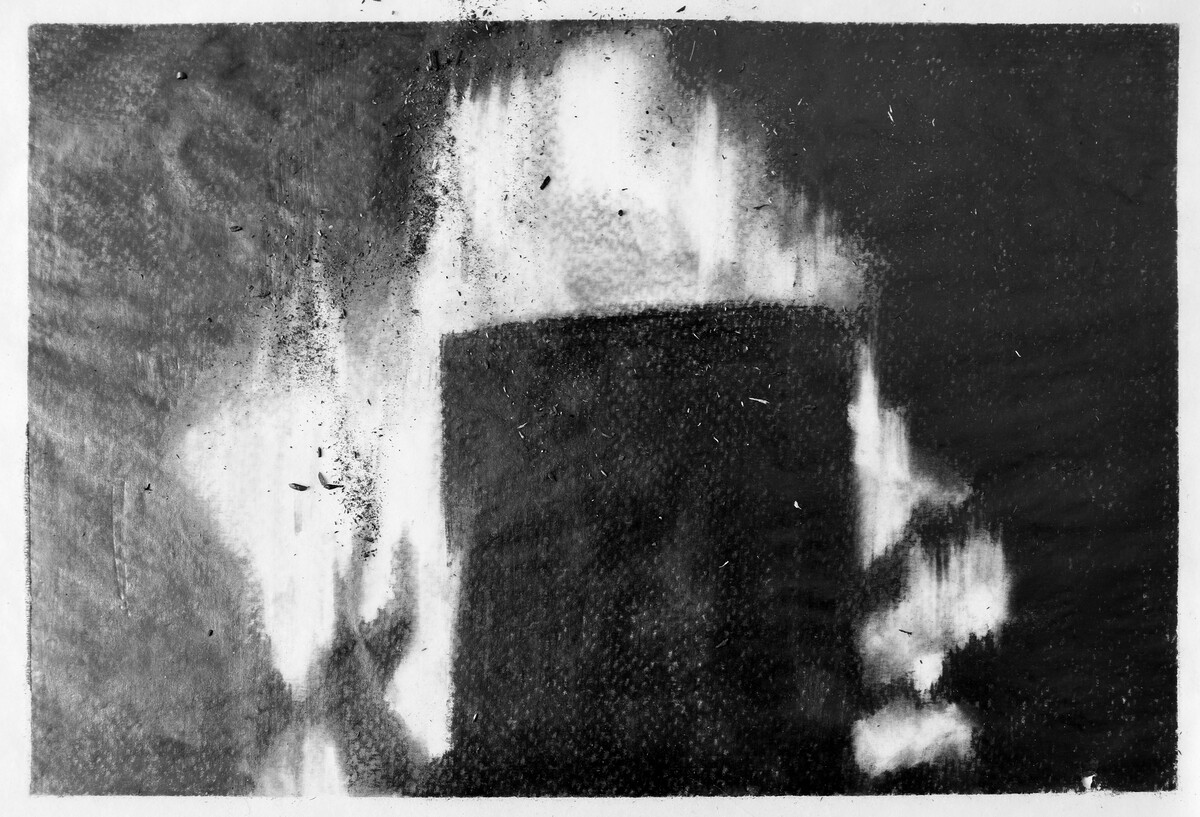

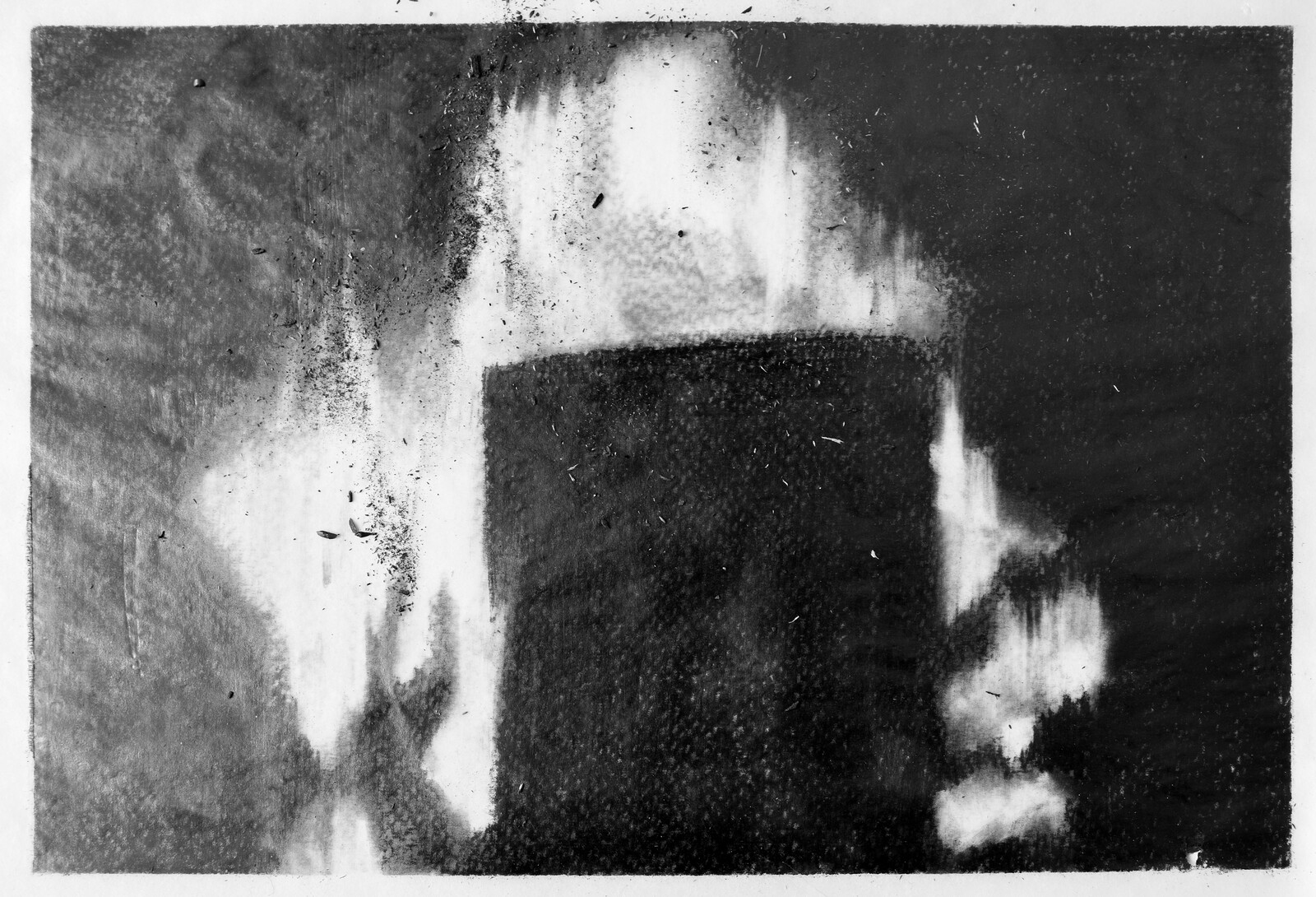

There is flame, there is light. The flame scorches my pages, light illuminates and brightens them. When I write with the flame, it is because something truly horrific has stolen my sight, then I burn. I write with light.

—Yvonne Vera1

On December 11, 1978, an attack by guerrilla combatants on a fuel storage facility in Southerton, Salisbury (as Harare was then known) was a major success in the liberation struggle (chimurenga), which two years later brought independence to Zimbabwe. The assault destroyed twenty-five of thirty-two giant storage tanks in the capital, extinguishing seventeen million gallons of diesel, aviation fuel, and gasoline.2 Shaky Associated Press footage from the incident shows the tanks ablaze. Over the roar of millions of dollars-worth of fuel on fire, the voice of a male onlooker exclaims in surprise as another tank catches light: “Oh! There’s the other one going…God, asseblief (please).” He is shaken. The voice of a woman interjects to ask if he is alright.3 There are quick cuts between shots, and breaks in the audio only accentuate the raging sound of the blaze when it returns. The footage turns to day and the fire continues, now attended to by dense smoke which fills the sky. A pan of the camera shows it extending over the city, engulfing buildings several stories tall. The commentary is gone.

Local accounts from the time describe a black specter visible as far as fifty kilometers away from the capital, and the presence of ghosts and conjuring, of magic and spirits, and of fuel and fire as a slippery medium of liberation, continues to haunt the incident.4 In the explosion and the destruction which followed, apparition-guerrillas appear from nowhere and vanish into the thickening black air, aided by a training in combat and cosmology. The performative dimensions of liberation are revealed, enacted as much through the crippling of oppressive systems as through the seemingly magical, surprising and highly public means through which this is done. Spirits are enlisted in the struggle, extending its action from the field of the present into the past and future too. A narrative of complex and polluted motivations unfolds. “Liberation” becomes performative action too—as freedom, then tragedy and farce—involving trickster spirits who promise salvation but bring shame instead. While the smoke may have cleared, it is still possible to feel the reverberations from Southerton, to understand its seismic effects amid a new context of choked fuel supplies and blackened air and to seek out what emancipatory strategies—rooted in combat and conjuring—still hold potential to be ignited today.

Black Specter

The fire at Southerton burned for six days, destroying a quarter of the country’s fuel reserves and was only quelled when support was flown in from Johannesburg. The first significant, searing attack in the capital, this campaign was decisive as the liberation movement sought in these advanced stages of the war to undermine the Rhodesian colonial forces tactically—“cutting the vein that fueled the Rhodies war machinery”—and also in the imaginary of the people—“God, asseblief;” “are you alright?”5 That civil unrest had entered the heart of the nation significantly reduced the visible might and power of the Rhodesian regime and simultaneously communicated the tactical and technological strength of the liberation movements, supported by armament and training from sympathetic and allied states. Beyond its immediate effects, the fire was an attack on a colonial imaginary leveraged on White supremacy and Black inferiority. As the Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith said at the time, for the regime, the incident was “a great disaster, and we must not pretend otherwise.”6

Tuning in from Salisbury, where the sky turned black with revolutionary fervor, covert guerrilla broadcasts from Maputo and Lusaka underscored the importance of the event in the minds of the public. Transmissions from the two wings of the liberation movement followed a similar rousing format before dispatches claiming responsibility for the attacks from the frontline were disseminated to the people. For the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), the Voice of Zimbabwe show began with a chimurenga song, followed by recordings of gunshots and the battle cry “The People of Zimbabwe, Victory is Certain!” Listeners to the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) broadcast were met with the roar of a lion, gunfire and then a rendition of the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) song “ZIPRA is Invincible!”7

These attacks served to weaken the Rhodesian regime, but they were also strategic as part of a theater of ideology through which combatants as political agents engaged and developed the consciousness of the wider public. They served as acts of mass mobilization, adding fuel to the desire for freedom and, through decisive punctures, opened up ruptures in the perceived dominant order towards other, possible worlds already in the wings. Mass mobilization was certainly supported by these sensational and violent tactics, but it was also enacted through quotidian performances in a minor key too, which served to stitch the foment of revolution surreptitiously into everyday life, through conjoined blackened mediums of fire, smoke, broadcast, voice, and politics.

There are conflicting accounts of exactly who was involved in the attack on the Southerton fuel storage. Both military wings of the chimurenga (ZANLA and ZIPRA) claim the victory, with differing yet detailed and compelling narrations of how it was enacted. What is known for certain is that the combatants involved in the attack were able to steal away, evading capture and leaving an elusive vacuum into which struggles over the political capital still to be garnered from this event now burn bright. This magical ability of Zimbabwean combatants to disappear into thin air (and equally importantly, to return again) is buried in an overlooked footnote in David Lan’s text on the relationship between guerrillas and spirit mediums in the chimurenga: “common is the story of the warrior who, when forced into a corner from which he could not escape, flew up into the air and disappeared.”8

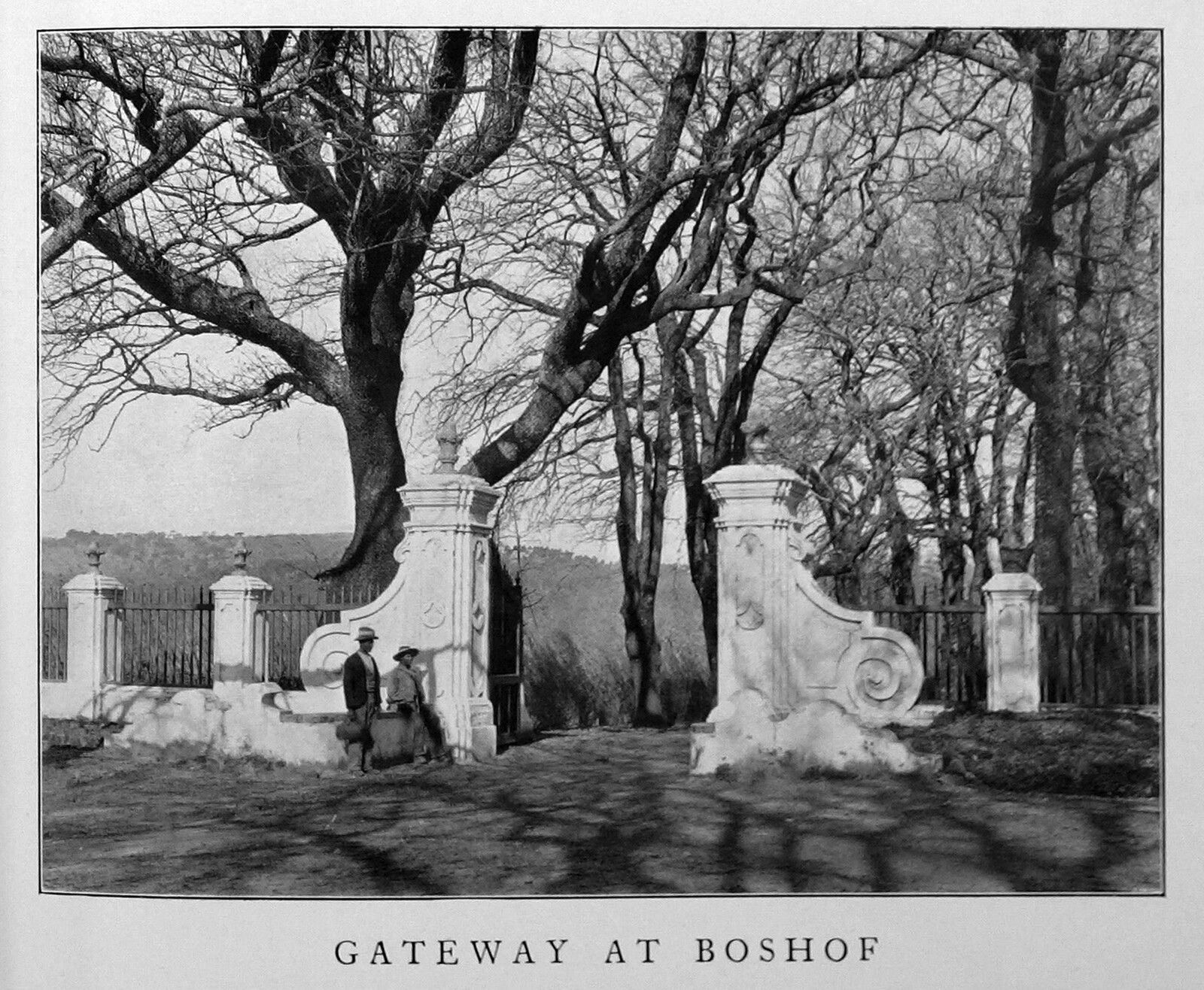

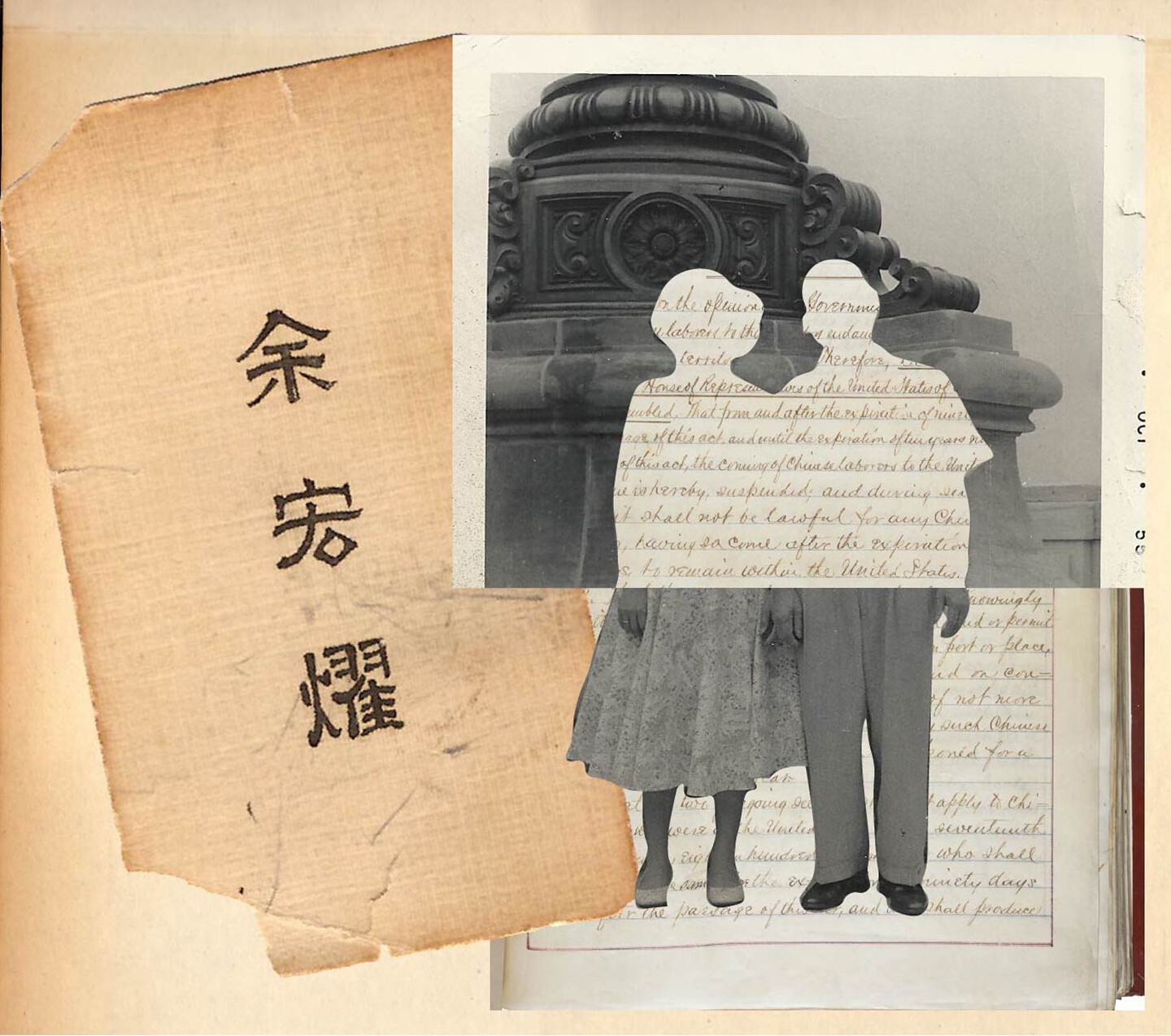

This disappearing-reappearing act took multiple scales. When Zimbabweans joined the armed movement, they were sent to training camps outside the country in supportive states on the continent such as Mozambique, Tanzania, and Angola, but also further afield: to Russia, China, and North Korea, amongst others. As Lan writes, this practice which, in part, began out of necessity, became ritualized, serving as a rite of passage into the movement: “[no-one] was considered a fully fledged guerrilla unless she or he had crossed the borders of Zimbabwe into another country for training before taking up arms.”9

Guerrillas adopted noms-de-guerre and, for a number of reasons, on return to the country after training abroad were often deployed in areas unfamiliar to them.10 For the public back home, this served to accentuate their otherworldliness (and exceptional abilities as a result), but also conversely asserted their connection to the country and cause. Their commitment to the chimurenga and the flight and reinvention that this required deepened their connection to the struggle to confront the alienation that colonialism had engendered between people, their land, and associated collective practices of being, justice, and ownership. This was an intergenerational reckoning. In Chikowero’s words:

When Zimbabweans recrossed the borders as guerrillas, their return was both physical and spiritual, symbolizing a critical moment in transgenerational reconstitution. Theirs was a return of the repressed in possession mode. Guerrilla deployment was led, accompanied, and guided by the ancestors.11

Departure, education, initiation, and return paradoxically served to connect combatants more intimately to the land itself, and to the cosmologies through which relations to land were asserted in the country. It also coupled the combatants of this second chimurenga with political leaders and spirit mediums of the first—Hwata, Nehanda Nyakasikana Charwe, Mashayamombe, Kaguvi Kaodza Gumboreshumba, Mlimo, Chingaira Makoni, Muchecheterwa Chiwashira, and others—who were killed at the end of the nineteenth century by the capitalist-colonial forces of the British South Africa Company.12 Mhoze Chikowero writes how the involvement of spirit mediums in this struggle particularly terrified the colonialist forces as “possessed bodies of African memory that defy Cartesian, western linear time and notions of individual justice and rights over (stolen) property.”13 Nehanda’s famous last words underscore this. The medium is said to have gone to the gallows dancing and laughing before announcing that her “bones would rise again.”14

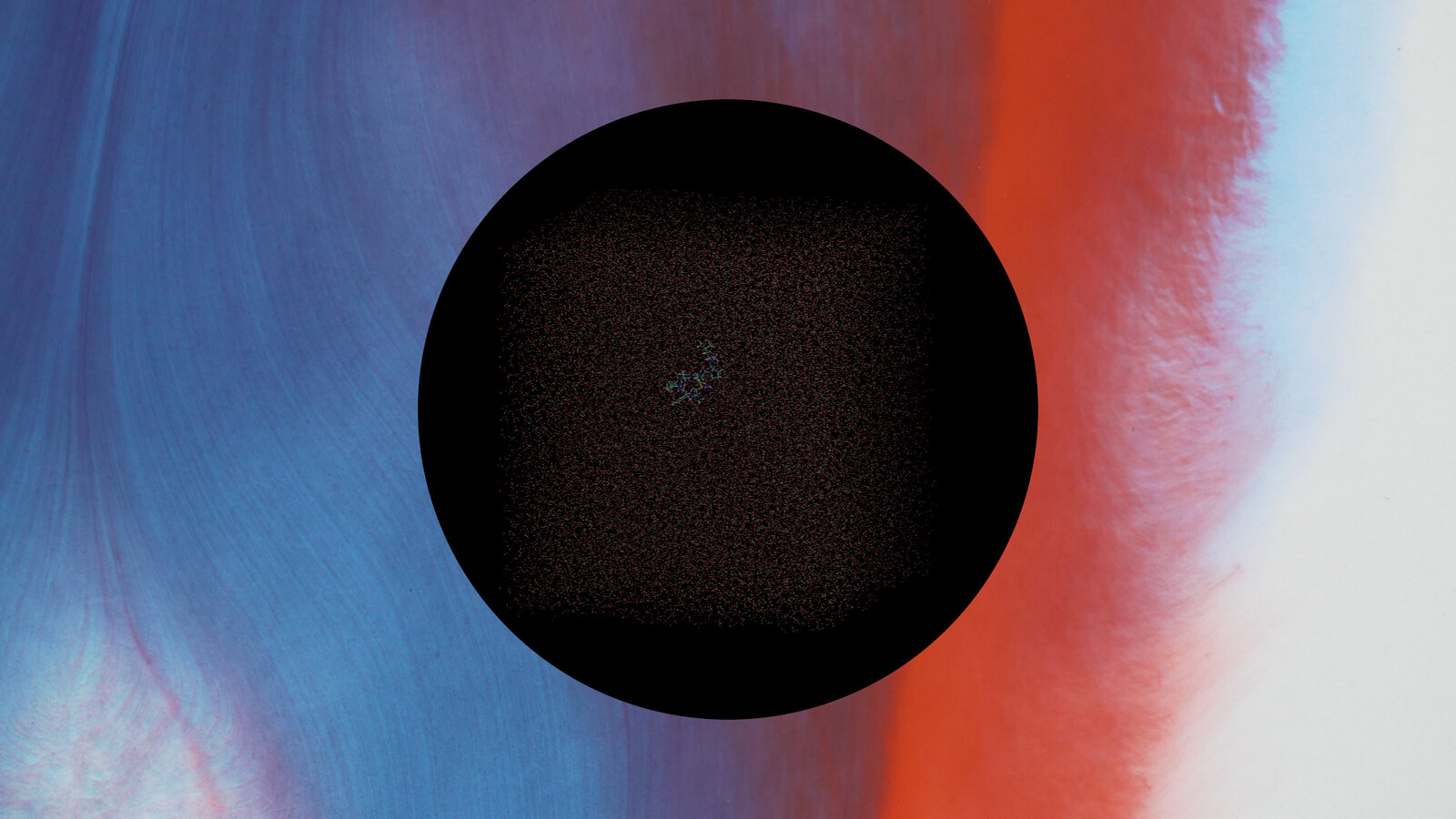

The artist Nolan Oswald Dennis describes the potential of black radical thought as offering a means of wrenching open the emancipatory “shadow” worlds which exist alongside our own, “not as a catalyst for the future or reflection on the past, but as a shadow or diagram of the longness of now (or as the late Keorapetse Kgositsile describes it, the pastpresentfuture).”15 Colonial forces, cognizant of their power, sought to dismantle such conceptions of time and place in Zimbabwe through the criminalization of acts through which spirits were conjured and those who enacted them. Nonetheless, spirit mediums played direct roles in supporting the second chimurenga by assisting combatants, providing spiritual support and training for survival in the bush.16 Their connection to the ancestral world extended this beyond the lived realm too, as the memories of Kumirai Jeke, a ZANLA war collaborator, recalls:

There was Chimbikiza and there was Gweshe. Both men were clearly genuine mediums from our great past. They could cast spells on enemy soldiers to get lost in mysterious mist, and they could organize mystical birds to lead the comrades to safety.17

Haunted Matter

Diesel is an extraordinary substance. Composed of so-called “saturated” and “aromatic” hydrocarbons, paraffins, naphthalenes, and alkylbenzenes, this heavy, oily fuel comprises large hydrocarbon molecules that evaporate slowly, making it more efficient and more desirable than petrol. This substance takes its name not from its own inherent or chemical qualities, but instead from the German mechanical engineer—Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel—and his invention of an engine which provided for the ignition of fuel by mechanical compression. This compression causes a rise in air temperature which creates the conditions for a kind of magic; spontaneous combustion without flame or spark as an igniting trigger.

While the exact composition of diesel varies, it is largely composed of crude oil that has undergone a process of fractional distillation. This process—another kind of magic—transmogrifies the viscous-black of crude oil into a form that can fuel combustion and the furious pace of so-called progress that attends engines of the modern day. In the distillation column—an almost comically simple piece of instrument-architecture—the compressed dregs of impossibly large quantities of long dead organisms held in the Earth under immense heat and pressure are separated into fuels of differing chain lengths, boiling points, molecular weights, viscosity, qualities of ignition, and color.

Diesel is the very matter of haunting, composed of former vestigial flickers of life that occupied the Earth’s seas and oceans millions of years ago and whose presence lingers as a result of the specific conditions of their passing, sites of deposition, and collective decomposition. The individual organisms whose afterlives are held within diesel are largely invisible to the naked eye, but under a microscope are revealed to be strange, ghostly white and highly transparent figures with awkward, glowing bodies which appear, deceptively, to hold little to no interior life at all. Death also lingers in the story of Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel too, who died under mysterious circumstances. In macabre scenes which followed, his body was happened upon twice at sea vast distances apart from each other by separate boat crews who returned it to the water. First, as tragedy, on account of his being reportedly in such an advanced state of decomposition, and second, as farce, a result of inclement weather.

Diesel N’anga

Death closely attends any discussion of diesel. The current price of diesel in Zimbabwe is US$1.35 per liter.18 This price has seen sharp increases as the country has struggled through economic crises in the last decades. Most recently, on January 14, 2019, an overnight increase in diesel prices from US$1.38 to US$3.11 made it the most expensive fuel in the world, and elicited three days of seemingly spontaneous yet highly organized popular protest. Spontaneous combustion without flame, these protests resulted in hundreds of injuries, including reports of seventy-eight gunshot wounds and twelve deaths at the hands of security forces. Violence was meted out in multiple forms, including through severing mediums of communication.19 In a longform blog post written in Bulawayo during this period, Tinashe Tafirenyika captures the listlessness, strange “anger and agitation” and the quiet weight of death in the air—simultaneously intimately and collectively experienced: “Horror does not wait for you to shut your eyes and drift off before it visits.”20

Just over ten years prior, in 2007, a strange incident gripped the beginning of President Mugabe’s last decade in power, while the country once again suffered from fuel shortages and the price hikes and queues for basic commodities that followed. Government minutes of July 27 show that spirit medium Rotina Mavhunga presented forty liters of diesel, “four ‘golden boulders,’ and six packets of loose stones” to the ruling party politburo and top security chiefs as proof that, with the aid of the ancestral realm, she could acquire precious stones and conjure fuel from rocks.21 Previous oil explorations in the country had ended in 1993 after Mobil Oil ended a US$15 million, three-year exploration which found no viable deposits.

Mavhunga—also known as the “diesel n’anga” or “diesel mystic,” who was then a medium for the spirits Changamire Dombo and Sekuru Mboni—managed to convince the politburo to investigate her claims in more detail. A significant number of high level politicians were drafted in, acquiescing to the medium’s personal and channeled requests for Z$5 billion dollars, a car, farm land, and undertaking a number of ritual performances including having fuel splashed on their bodies at her shrine.22 Based on the success of these initial efforts, a second mission was sent by the president but was less convinced when Mavhunga was unable to produce more fuel. A network of pipes lodged in the rocks at the site of the miracle in the Maningwa Hills was later discovered, as were a number of accomplices to the scheme. One infographic in The Standard described the stages of the remarkably simple con: “(1) Bowser of diesel hidden at top of hill, (2) Assistant turns on fuel supply at appropriate moment, (3) [Mavhunga] strikes rock and fuel flows, (4) Audience of officials duped.”23

After several years on the run, Mavhunga was apprehended and charged with defrauding the state and making misrepresentations to government officials who—President Mugabe suggested—had fallen for a con on account of the medium’s beauty.24 Throughout the trial, Mavhunga continued to command the nation’s imagination with a mix of fascination behind the spiritual dimensions of the case, the suggested implication of high level officials, and reflections on what could be read from this incident of the state of the nation thirty years after Independence.

When asked why it took police so long to make an arrest, political commentator John Makumbe suggested: “They were scared. I even think they knew where she was hiding but I think they didn’t know whether, if they tried to arrest her, whether she wouldn’t turn them into lizards or something like that.” Makumbe poured scorn on the affair, and its implications for Zimbabwe’s political leaders at the time:

They actually believe they are in power because their ancestors are keeping them there. They actually believe they deserve to be there because they have powerful totems and they believe their powerful totems will get them to be President and Vice President one day.25

During the court case, both Mavhunga and one of her accomplices fell—quite literally—into a trance. The judge abruptly adjourned and left the court while, according to witnesses, Mavhunga—speaking with an “unfamiliar voice”—acted as a conduit for the spirit of Changamira Dombo and accused government officials of having prompted the scheme, warning them of the limits of dealing with spiritual matters in the living realm.26 The possession lasted nearly an hour after which more prosaic court proceedings resumed with the state calling witness and expert testimony including from scientists who had tested the initial miracle-fuel for veracity. It was confirmed as “pure diesel.”27

Mavhunga initially failed to appear for the first hearing of the judgement due to ill health, and then again, as she was conducting ritual ceremonies elsewhere in the country. On the last occasion, her lawyer was unable to get enough fuel to drive to the court.28 In the final sentencing, she admitted wholly to the charges but left open the possibility of sourcing diesel in the country which had been so roundly and publicly dismissed as nonsense. Mavhunga told the court that she had in fact disobeyed the spirit of Dombo, who had shown her where to source diesel from rocks, instead conspiring with her followers and an unnamed government official to “play games.” In a further twist, Mavhunga told the court that her real name was actually Nomatter Tagarira, suggesting that Mavhunga was another spirit that possessed her before Dombo, and perhaps the cause for the errancy (or deviation?) that ensued.29

African Quality

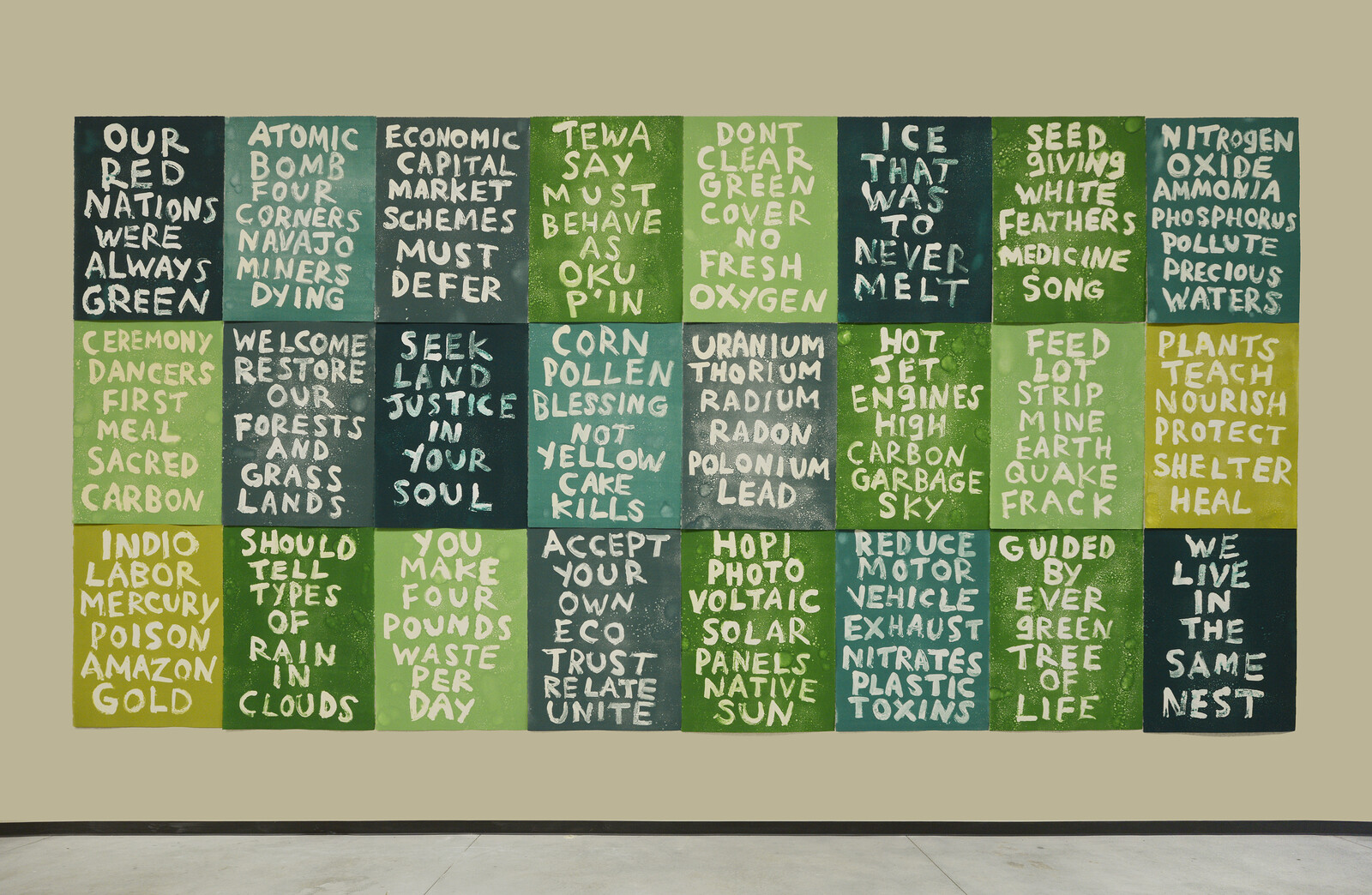

Emissions from diesel are significantly more polluting than other fuel sources. A 2016 report by Public Eye showed that Swiss trading companies, one of which controls 50% of the market share of imports into Zimbabwe, were taking advantage of weaker regulation on the continent to produce what the industry terms “African Quality” fuels with high contents of toxic substances, several hundred times over the European limit.30 Shockingly, the investigation found that these African Quality fuels are produced using petroleum extracted in West Africa which, at source, is initially of much higher quality before being “blended” in Europe (and offshore) to produce a cheaper quality of fuel that is shipped back. The health impacts of this unethical practice are exponential, and poor air quality is one of the leading causes of morbidity and premature death worldwide.31

There are limited local studies of morbidity from ambient air pollution in Sub-Saharan Africa, but urban pollutant levels have generally been found to be ten to twenty times higher than WHO recommendations.32 Air pollutants in the form of particulate matter, black carbon, sulphur, and other toxic contaminants lodge in the lungs, cause heart disease, lung cancer, mucus secretion, reduce lung function, and result in the increased likelihood of suffering from asthma and chronic bronchitis. A year after the Public Eye report, in 2017, the Zimbabwe Ministry of Energy and Power Development announced a phased transition reducing acceptable qualities of sulphur content in diesel fuel from five hundred parts per million to fifty. The European limit is ten.

In November 2020, the Australian oil and gas exploration company Invictus Energy announced that it had begun field operations drilling for oil and gas in Zimbabwe. In an echo of Mobil’s previous efforts, the company intends to invest between US$15–20 million per well, and is already undertaking preliminary work with plans for “seismic acquisition” to commence in 2021. Reports of these explorations deride the earlier diesel n’anga incident, dismissing Mavhunga as a liar before evidencing many of her claims as warranting significant financial and technological investment.33

Ether

Katherine McKittrick draws our attention to the connection between psychic and physical geographies in Frantz Fanon’s understandings of Black liberation and anticolonial strategies. McKittrick frames this through the vectors of “deep space,” or “the poetics of landscape [that] add new contours to geographic inquiries” through which contemporary struggle must be engaged and understood.34 Here, soil, nation, and race are concomitant. In Zimbabwe, we must also add ether: as air, as spirit, as fuel, and as flight.

At its heart, this close reading of crude and sticky matter reveals multiple, parallel, and possible afterlives of chimurenga suspended within.35 In these scenes are apparition-guerrillas: comrades who elude fixity, haunting our present with their absence and yet present enough for their impact to be keenly felt. We encounter the atmospheric conditions of liberation: conjured through smoke, thickening of air and airwaves, and aided by unfamiliar voices and mystical birds. We also witness the pollution of this environment: enacted through profit-driven mentalities, “seismic acquisition,” corrupted energies, and racist policies which equate “African Quality” with toxic quantities of sulphuric contaminants.

There is a black specter hanging over this scene. But perhaps, it is not only one which foreshadows death. While Mavhunga may have served her time, the spirit of Changamira Dombo continues to evade the law. With this knowledge, we too may hold to the possibility of a relationship to haunting that attends to the stuff of horror, all while searching for the flickers of life which remain to be ignited within. Here, amid mysterious mists and toxic air, lies the potential for “return of the repressed in possession mode…led, accompanied and guided by the ancestors.”36

Yvonne Vera, “The flame that scorches my pages,” The Chronicle, Zimbabwe, January 21, 1997. Reprinted in Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats, eds. Tinashe Mushakavanhu and Nontsikelelo Mutiti (Richmond and Harare: Black Chalk & Co., 2019), 45.

“Rhodesia Blaze a Major Setback,” The Washington Star, December 14, 1978.

Associated Press, “SYND 12 12 78 Guerrillas blow up oil depot, massive fire” (December 12, 1978), YouTube, July 24, 2015, ➝.

Interview with Fidelis Mukonori, Silveira House, Harare, August 16, 2017, quoted in Takawira Chatambudza and Mediel Hove, “The Zimbabwe people’s revolutionary army military operations in Makonde District and the attack on Salisbury’s fuel storage tanks, 1965–1979,” Small Wars & Insurgencies 30, no. 2 (2019): 367–391.

Evans Mushawevato, “The Bombing of the Salisbury fuel tanks: Shiri explains how the idea was hatched,” The Patriot, July 3, 2014, quoted in Chatambudza and Hove, “The Zimbabwe people’s revolutionary army.”

“Oil Blaze battle in final phase,” The Herald, December 14, 1978, quoted in Tjalling Yme Wiarda, “The 11th of December 1978 petrol-storage depot attack in Salisbury, Rhodesia: Research into past and present imaging” (Masters thesis, University of Antwerp, 2016).

Dumisani Moyo and Cris Chinaka, “Spirit Mediums and Guerrilla Radio in the Zimbabwe War of Liberation,” in Guerrilla Radios in Southern Africa: Broadcasters, Technology, Propaganda Wars, and the Armed Struggle, eds. Sekibakiba Peter Lekgoathi, Tshepo Moloi, and Alda Romão Saúte Saíde (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2020), 96–97.

David Lan, Guns and Rain: Guerrillas and Spirit Mediums in Zimbabwe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 135, footnote 13.

Ibid., 128–129.

Ibid., 125.

Mhoze Chikowero, African Music, Power, and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015), 237.

Ibid., 51.

Ibid., 53.

Tanya Lyons, “Guns and Guerrilla Girls: Women in the Zimbabwean National Liberation Struggle” (PhD diss., University of Adelaide, 1999), 83.

“Nolan Oswald Dennis/Options/2019,” Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, January 24 to March 9, 2019, ➝.

Lan, Guns and Rain, 74.

Interview with Kumurai Jeke by Sifelani Tsiko, Harare, September 12, 2019, in Moyo and Chinaka, “Spirit Mediums and Guerrilla Radio,” 94.

As of March 22, 2021.

An internet blackout—at first blocking social media and messaging apps, and then a full-scale “shut down” cutting off access through VPNs—was enforced, an act later ruled illegal by the Zimbabwean High Court.

Tinashe Tafirenyika, “On the shutdown of Zimbabwe,” Brittle Paper, January 27, 2019, ➝.

Nqaba Matshazi, “Zimbabwe: Diesel N’anga—the True Story,” The Standard, October 2, 2010; “Zimbabwe: Medium Offers Mugabe Fuel, ‘Golden Gifts,’’’ Zimbabwe Independent, August 10, 2007.

Reports of these gifts vary. See Matshazi, “Zimbabwe: Diesel N’anga.”

“Diesel N’anga released from prison,” The Standard, April 8, 2012.

Matshazi, “Zimbabwe: Diesel N’anga.”

“Police were scared of being turned into lizards,” Nehanda Radio, October 4, 2010.

“Zimbabwe: Diesel N’anga’s Case—Officials Bolt Out of Courtroom,” The Herald, May 10, 2008.

Ibid.

“Zimbabwe: Warrant of Arrest for Diesel N’anga,” The Herald, July 9, 2009.

“Zimbabwe: I Lied to the Nation—‘Diesel’ N’anga Confesses,” The Herald, April 17, 2008.

Marc Guéniat et al., Dirty Diesel: How Swiss Traders Flood Africa with Toxic Fuels (Lausanne: Public Eye, 2016).

Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum and Anette Prüss-Ustün, “Climate change, air pollution and non communicable diseases,” Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 97 (2019): 160–161.

Patrick Katoto et al., “Ambient air pollution and health in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current evidence, perspectives and a call to action,” Environmental Research 173, (2019): 174–188.

Lenin Ndebele, “Drilling down in Zimbabwe’s oil fields,” Business Live, September 24, 2020.

Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 23–24.

I am grateful to Sara Salem for conversations around the ideas of haunting and afterlives of struggle, and her phenomenal body of work on this in her recent book: Sara Salem, Anticolonial Afterlives in Egypt: The Politics of Hegemony (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020). The use of this term is after and in conversation with her work.

Chikowero, African Music, Power, and Being, 237.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.